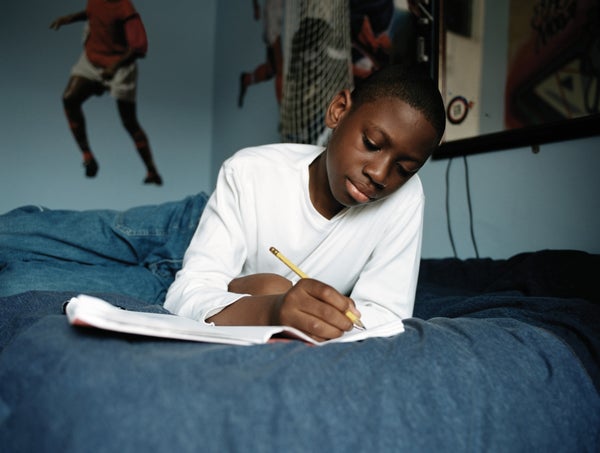

Handwriting notes in class might seem like an anachronism as smartphones and other digital technology subsume every aspect of learning across schools and universities. But a steady stream of research continues to suggest that taking notes the traditional way—with pen and paper or even stylus and tablet—is still the best way to learn, especially for young children. And now scientists are finally zeroing in on why.

A recent study in Frontiers in Psychology monitored brain activity in students taking notes and found that those writing by hand had higher levels of electrical activity across a wide range of interconnected brain regions responsible for movement, vision, sensory processing and memory. The findings add to a growing body of evidence that has many experts speaking up about the importance of teaching children to handwrite words and draw pictures.

Differences in Brain Activity

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The new research, by Audrey van der Meer and Ruud van der Weel at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU), builds on a foundational 2014 study. That work suggested that people taking notes by computer were typing without thinking, says van der Meer, a professor of neuropsychology at NTNU. “It’s very tempting to type down everything that the lecturer is saying,” she says. “It kind of goes in through your ears and comes out through your fingertips, but you don’t process the incoming information.” But when taking notes by hand, it’s often impossible to write everything down; students have to actively pay attention to the incoming information and process it—prioritize it, consolidate it and try to relate it to things they’ve learned before. This conscious action of building onto existing knowledge can make it easier to stay engaged and grasp new concepts.

To understand specific brain activity differences during the two note-taking approaches, the NTNU researchers tweaked the 2014 study’s basic setup. They sewed electrodes into a hairnet with 256 sensors that recorded the brain activity of 36 students as they wrote or typed 15 words from the game Pictionary that were displayed on a screen.

When students wrote the words by hand, the sensors picked up widespread connectivity across many brain regions. Typing, however, led to minimal activity, if any, in the same areas. Handwriting activated connection patterns spanning visual regions, regions that receive and process sensory information and the motor cortex. The latter handles body movement and sensorimotor integration, which helps the brain use environmental inputs to inform a person’s next action.

“When you are typing, the same simple movement of your fingers is involved in producing every letter, whereas when you’re writing by hand, you immediately feel that the bodily feeling of producing A is entirely different from producing a B,” van der Meer says. She notes that children who have learned to read and write by tapping on a digital tablet “often have difficulty distinguishing letters that look a lot like each other or that are mirror images of each other, like the b and the d.”

Reinforcing Memory and Learning Pathways

Sophia Vinci-Booher, an assistant professor of educational neuroscience at Vanderbilt University who was not involved in the new study, says its findings are exciting and consistent with past research. “You can see that in tasks that really lock the motor and sensory systems together, such as in handwriting, there’s this really clear tie between this motor action being accomplished and the visual and conceptual recognition being created,” she says. “As you’re drawing a letter or writing a word, you’re taking this perceptual understanding of something and using your motor system to create it.” That creation is then fed back into the visual system, where it’s processed again—strengthening the connection between an action and the images or words associated with it. It’s similar to imagining something and then creating it: when you materialize something from your imagination (by writing it, drawing it or building it), this reinforces the imagined concept and helps it stick in your memory.

The phenomenon of boosting memory by producing something tangible has been well studied. Previous research has found that when people are asked to write, draw or act out a word that they’re reading, they have to focus more on what they’re doing with the received information. Transferring verbal information to a different form, such as a written format, also involves activating motor programs in the brain to create a specific sequence of hand motions, explains Yadurshana Sivashankar, a cognitive neuroscience graduate student at the University of Waterloo in Ontario who studies movement and memory. But handwriting requires more of the brain’s motor programs than typing. “When you’re writing the word ‘the,’ the actual movements of the hand relate to the structures of the word to some extent,” says Sivashankar, who was not involved in the new study.

For example, participants in a 2021 study by Sivashankar memorized a list of action verbs more accurately if they performed the corresponding action than if they performed an unrelated action or none at all. “Drawing information and enacting information is helpful because you have to think about information and you have to produce something that’s meaningful,” she says. And by transforming the information, you pave and deepen these interconnections across the brain’s vast neural networks, making it “much easier to access that information.”

The Importance of Handwriting Lessons for Kids

Across many contexts, studies have shown that kids appear to learn better when they’re asked to produce letters or other visual items using their fingers and hands in a coordinated way—one that can’t be replicated by clicking a mouse or tapping buttons on a screen or keyboard. Vinci-Booher’s research has also found that the action of handwriting appears to engage different brain regions at different levels than other standard learning experiences, such as reading or observing. Her work has also shown that handwriting improves letter recognition in preschool children, and the effects of learning through writing “last longer than other learning experiences that might engage attention at a similar level,” Vinci-Booher says. Additionally, she thinks it’s possible that engaging the motor system is how children learn how to break “mirror invariance” (registering mirror images as identical) and begin to decipher things such as the difference between the lowercase b and p.

Vinci-Booher says the new study opens up bigger questions about the way we learn, such as how brain region connections change over time and when these connections are most important in learning. She and other experts say, however, that the new findings don’t mean technology is a disadvantage in the classroom. Laptops, smartphones and other such devices can be more efficient for writing essays or conducting research and can offer more equitable access to educational resources. Problems occur when people rely on technology too much, Sivashankar says. People are increasingly delegating thought processes to digital devices, an act called “cognitive offloading”—using smartphones to remember tasks, taking a photo instead of memorizing information or depending on a GPS to navigate. “It’s helpful, but we think the constant offloading means it’s less work for the brain,” Sivashankar says. “If we’re not actively using these areas, then they are going to deteriorate over time, whether it’s memory or motor skills.”

Van der Meer says some officials in Norway are inching toward implementing completely digital schools. She claims first grade teachers there have told her their incoming students barely know how to hold a pencil now—which suggests they weren’t coloring pictures or assembling puzzles in nursery school. Van der Meer says they’re missing out on opportunities that can help stimulate their growing brains.

“I think there’s a very strong case for engaging children in drawing and handwriting activities, especially in preschool and kindergarten when they’re first learning about letters,” Vinci-Booher says. “There’s something about engaging the fine motor system and production activities that really impacts learning.”

A version of this article entitled “Hands-on” was adapted for inclusion in the May 2024 issue of Scientific American.