Dawn of the Zombie Journal: New Poster Celebrates History of OA Community Activism

Posted by Katherine Parker-Hay on 18 October 2023

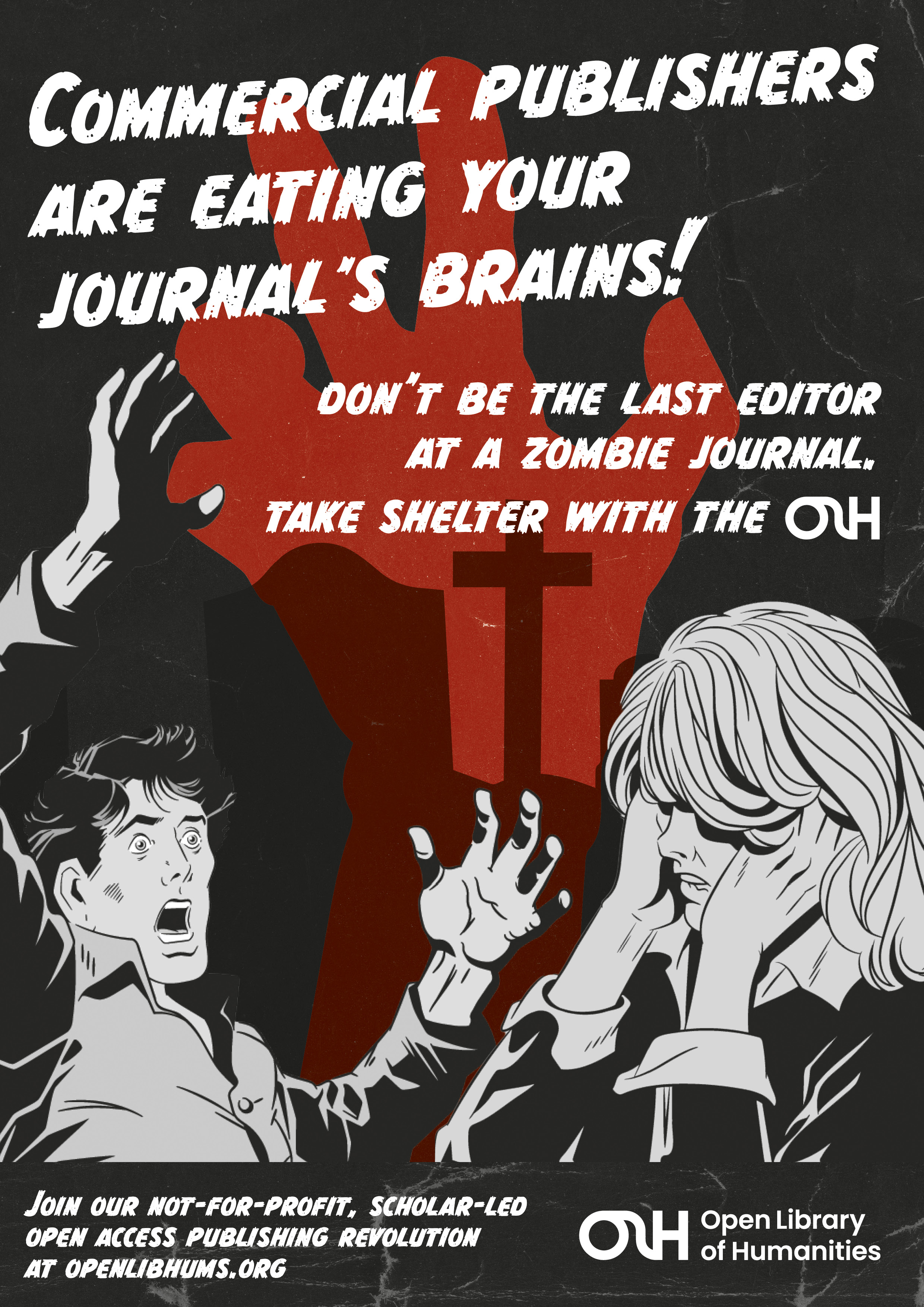

To celebrate Open Access Week 2023 (and its proximity to Halloween), the OLH is launching the Zombie Poster. This commemorates the term ‘zombie journal’, first used by linguists in 2015 following the mass resignation of editors at the Elsevier journal Lingua. Protesting Elsevier’s claim to ‘own’ their journal, the international linguistics community boycotted Lingua and launched the community-owned open access journal Glossa in its place (published by the OLH). What was left behind was dubbed ‘Zombie Lingua’.

With the commission of this original artwork and t-shirt run, we celebrate the spirit that made this political action possible and preserve it for the public record. We invite you to join us in photographing the zombie poster in ‘jump scare’ locations. Please also update your institutional glossaries. Let’s make sure the term ‘zombie journal’ has a lasting place in the Open Access vernacular!

The theme of this year’s Open Access Week is close to our hearts at the OLH: community over commercialisation. It asks us to remember open access’s origins as a political movement and align our models with that vision. Halloween is also creeping closer – a date that invites enough chaos and grotesquery to mess with dominant power structures. With all this deviancy in the air, the OLH invites you to gather close around the virtual campfire and listen to a ghoulish story from not so long ago…

We have trawled through the nooks and crannies of social media circa 2015 and conducted an interview with OLH editor and surviving witness Professor Johan Rooryck, to bring you a story of undead zombies and their vampiric capitalist overlords. Sit back and listen (if you dare!) to our story of insatiable commercial appetites, an ensemble of internet scholar-activists and an undead zombie journal that shambled on after having lost the support of its scholarly community.

A tale of ghoulish commercialisation

The story of how the highly regarded linguistics journal Lingua became Glossa is well documented, having gained widespread coverage over 2015 and 2016 as a lesson in the power of editorial boards to shape the future of academic publishing.

Facing pressure from the linguistics community, Lingua’s board asked their publisher, Elsevier, to transition to a fully open access journal. This request was refused. In a 2023 interview with the OLH, Rooryck remembers that around the same time Elsevier had begun to intervene in decisions about the journal’s editorial board, requesting appointments that Rooryck thinks were driven by market forces. Up to that point Rooryck had believed that the intellectual content of a journal was the domain of the academic community, even if technically the publisher ‘owned’ the title. Though little remunerated, (Rooryck says he would have ‘been better off [cleaning] windows in the neighbourhood’) his fifteen years of editorial work was primarily motivated by a sense of service to the linguistics community. He certainly had not, up to that point, considered himself a cheap contractor whose primary job was to generate profits for a commercial entity.

However, communications with Elsevier around this time made it clear that they saw the situation quite differently. Rooryck reflects that ‘at one point, editors get sick and tired of being bossed around by a commercial publisher, especially when you know full well that it is not in the best interest of the intellectual content of the journal’. With the publisher refusing to convert the journal to open access, and refusing to transfer ownership of the title, all six editors and thirty-one board members collectively resigned in protest and set out to launch a ‘new’ fully open access journal, Glossa. It has since been published with the OLH but is emphatically owned and governed by its General Assembly which is composed of the Editorial board, Editor-in-Chief and Associate Editor(s).

Elsevier retained the former journal name and logo and would continue to trade off Lingua’s reputation. There is something ‘really quite ghouling’ about the way that metrics are calculated, reflects Rooryck. Lingua’s output in the year after the resignation was largely based on material they had curated that had been in the pipeline. It took six years from the transition for Lingua to drop out of the H5-index top 20 at Google Scholar for Languages and Linguistics and for Glossa to proudly take that vacated place. In the protracted twilight zone, Lingua metrics and impact rankings continued to be drawn from the work of its previous editors.

Zombie Lingua

What happened next testifies to the energy, creativity, and wit of the linguistic community. They did not step back quietly and just hope that Lingua would fade away. Instead, they made it clear to all that the life and soul of a journal belongs to the commons. Spearheaded by Kai von Fintel and Eric Baković, the community launched a campaign which declared that Glossa was the rightful successor of the former journal. They announced Lingua was dead (Kia remembers Gillian Ramchand coining the term 'zombie journal', possibly in a private thread) and asked colleagues collectively to withdraw their labour.

Rooryck recalls the groundswell of support as the story blew up in the international press, and the online community quickly mobilised in support of the editorial team’s decision:

It was all organic. Quite natural. The idea of course was that the journal was dead to the community. And the fact that Elsevier wanted to make it continue made it into a zombie. Sort of brainless. Stumbling on, but without its original community.

He recalled that when he first heard the term, he ‘laughed out loud’ because ‘it captured so well the entire situation. I thought it was the perfect term’. Our conversation about zombies highlighted to me the significance of Elsevier’s decision to broaden Lingua’s scope, generalising the area of specialism beyond theoretical linguistics—which presumably had the effect of bolstering article submissions as the journal experienced the brain drain of its intellectual leadership. Zombies have no personality, no need to belong. They are desensitised and hollowed out, attracted simply to that which is different from them (that which is alive) and they pursue it relentlessly.

Of course, there is also a long history of zombies as carriers of social satire, with their singular drive to consume leaving everyone around them in an apocalyptic half-life existence. Gorging on brains in a futile attempt to ease the pain of being dead, zombies articulate the realities of our prevailing models of academic publishing. As Roger Luckhurst writes in Zombies: A Cultural History (2015), zombies are ‘a contagion, driven by an empty but insatiable hunger to devour the last of the living and extend their domain until we reach the End of Days’. They are the ‘decomposing poor relation of aristocratic vampires’, emerging from the margins of empire in Haiti and the French Antilles. Corporate publishers thrive by appropriating our intellectual labour which is ultimately part of a much wider drive towards commercialisation that has infiltrated every aspect of higher education, gradually but relentlessly enveloping our scholarly communities and leaving them hollowed out, industrialised, metaphysically evacuated.

Radical openness

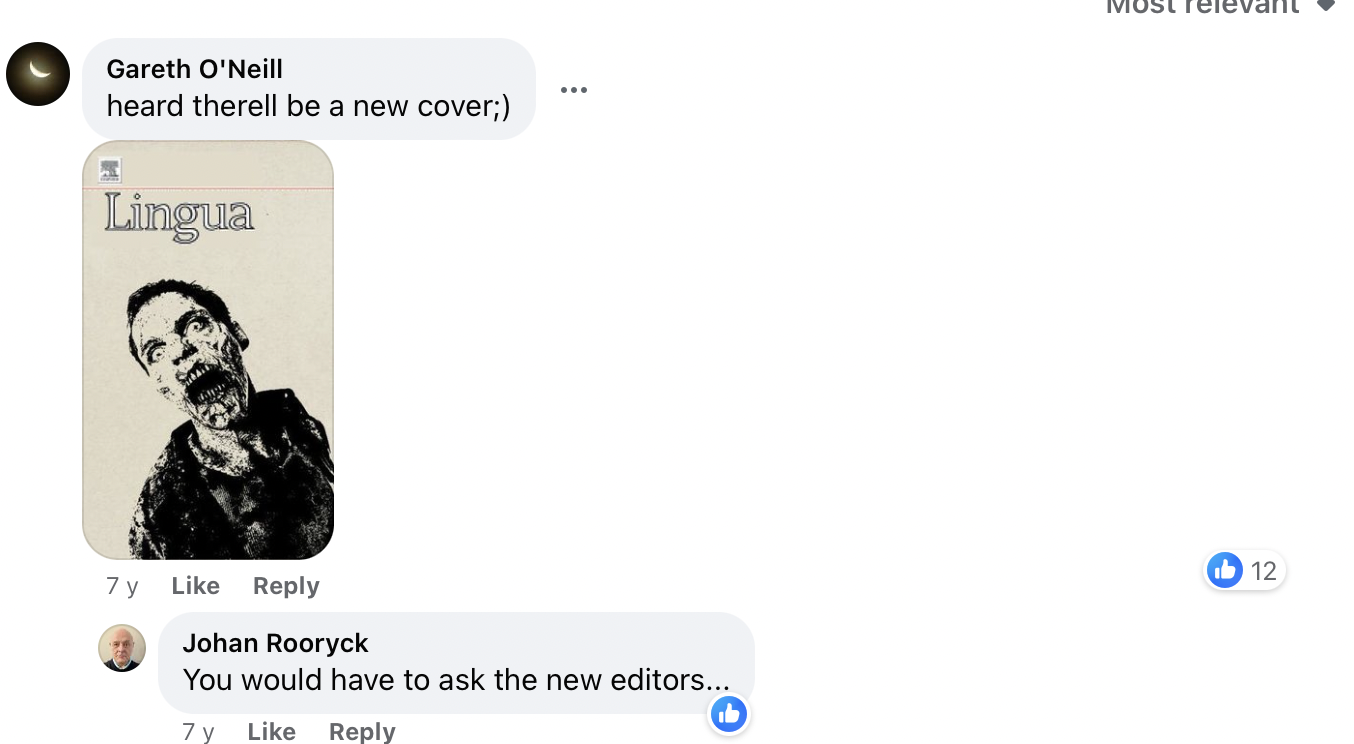

Doing the sleuth work for this post sent me back into the world of Facebook in 2015 where this moment of collective defiance and satire has been preserved. Scrolling through timelines, I found people marking up the Lingua cover with zombie imagery, writing to the new editorial board to make them aware, playfully embracing the term ‘deviant linguists’ that featured in a headline. Facebook also preserved calls for temperance but in a context where some were claiming that ‘toppling Elsevier had become a kind of collective fetish’, with everyone wanting to be ‘open access heroes’. Sifting through this electronic paper trail, I was charmed by Rooryck’s unapologetic public declaration that ‘I’m doing this purely for idealistic reasons’.

Figure 1: Facebook thread, 11th November 2015

Elsevier responded to the publicity in the way that is typical of big corporations. They released a bland statement purporting to ‘clarify’ the ‘misunderstandings’ surrounding the resignation. The statement includes multiple face-palm moments, not least of which is a claim to be the Lingua founders. The community took to Facebook to encourage people to consult Lingua’s first issue where the introduction states quite clearly that the founders are the 1949 founding editors not the publisher. Elsevier’s statement also accused Rooryck of wanting to seize ownership of the journal, which on request was publicly corrected to: ‘The editors of Lingua wanted for Elsevier to transfer ownership of the journal to the collective of editors at no cost’.

Rooryck revealed to me that Elsevier’s public statement framed his decision to go open access as careerist and self-motivated, misrepresenting private communications with the publisher. He recalls that the negotiations were ‘gentlemanly’ at first, but then he began to hear about rumours circulating that appeared to be ‘a deliberate attempt to blacken my name’. Of course, this comes straight from the corporate playbook and works so well because it happens behind closed doors.

In an act of radical openness, Rooryck responded to these tactics by publishing the entire correspondence with Elsevier on his personal blog. These now publicly accessible documents include an email chain that contains the gloriously performative utterance: ‘I have made your statements to these reviewers public, by the way and will meet your underhanded tactics with complete transparency. I will also make this correspondence public’.

The published correspondence reads like an object lesson in what can still be done when ‘saying no to power’ feels futile. The editors recognised that the battle over legal ownership could not be won. So, they turned their backs on the journal’s existence. They realised that they could not fight the stipulation in their contracts, which disbarred them from working on another journal for a defined period. So, they found interim editors for Glossa.

Journal publishing runs on reputation and because a huge part of a journal’s reputation rests on the work of its editors, when they acted collectively they represented a dangerous force. The editorial team leveraged their prestige, networks, and resources to make a very public bet that there was a truth that ran deeper than the legal small print: what makes a journal precious is the accumulated labour and vision of its scholarly community which has little to do with the publisher. Their approach illustrates that even when we can’t ‘say no to power’, we can acknowledge its workings and yet still find other kinds of creative refusal. We are never completely trapped. Walking away, the editors were prepared to relinquish their journal’s title and take the risk that the community would recognise where a journal’s value lies and follow them to Glossa.

The OLH Zombie poster!

Journal flipping is not new. There has been a steady and growing exodus of journals leaving commercial publishers, and our research suggests that there has been a groundswell of journals 'flipping' to open access in 2023 (which has been accelerated as a result of commercial publishers ditching their less profitable titles). However, it can be difficult to join the dots and see these individual actions as part of a growing political movement. Commercial publishers tie editors into contracts that prevent them from running another journal, sometimes for years, which strangles exploratory conversations about how things might work differently. These contracts also stipulate that the publisher owns all editorial labour as their property, including correspondence, so dissenting voices are effectively silenced. As part of our investigation, the OLH team has reached out to other editors involved in flipping formerly subscription journals to open access. Many came forward with similar stories. Others were not able to speak because of fear of legal consequences.

Don’t be the last editor at a zombie journal. Our poster reminds academics what can happen to a journal in the struggle with commercial publishers to regain community control of our research. A zombie journal may look like the real thing: severance is protracted due to the way rankings work. It may feel and sound familiar. But a zombie is not alive. It preys on life. Channelling the eery monologue of televised scientist Richard France from the 1978 cult classic Dawn of the Dead, we warn you of the challenge of eradicating that which has human likeness: zombies are ‘pure motorised instinct with remembered behaviours from normal life’.

In historicising the term ‘zombie journal’, I and the wider OLH team hope to identify editorial frustrations at commercial practices as part of a wider movement for change. I have seen the tireless work that Rooryck has undertaken since launching Glossa, regularly offering guidance and support to other frustrated journal editors who need inspiration and guidance to find another way. During our interview, I asked Rooryck whether he saw his work as activism. ‘Yes, of course’ he replied, ‘but this is definitely something that came with Glossa. One of the things that I learnt with the move was that it is liberating. But with that liberation comes responsibility’.

Despite these difficulties, sites of resistance to the commercial control of academic research do exist. As any classic zombie film makes abundantly clear, we are more likely to survive in groups, where we can share resources, skills, and knowledge. At the OLH, we want to encourage more editors to find ‘shelter’ with diamond open access publishers and know that there are alternatives even in times of austerity and rampant commercialisation. The diamond open access organisations participating in this year’s Open Access Week have led the way in providing innovative solutions to otherwise prohibitive article processing charges (APCs) and put sharing resources at the heart of a collective mission to bring journals back into community ownership.

Keep the term alive, keep zombie journals dead!

Our work at the OLH is indebted to decades of internet activism, of which the linguistics community's 2015 zombie campaign is just one example. As we have seen, however, it is easy for these moments of resistance that use social media to get lost in a huge flow of Internet data. How can we ensure that these stories don’t get buried on someone’s timeline? How can we preserve flashes of community activism so that they may inspire change in our institutions and day-to-day activities?

In researching this blog post, I had to scroll through year after year of Facebook content to recover the original discussions around the term ‘zombie journal’. I was stalled time and again by broken links to blog posts that hadn’t been preserved. When I did find what I was looking for, I was humbled by the perfectly preserved boldness of a group of people who were willing to take a stand, but also the pathos that these voices are now buried by almost a decade’s worth of content that has piled up like the settled snow after an avalanche.

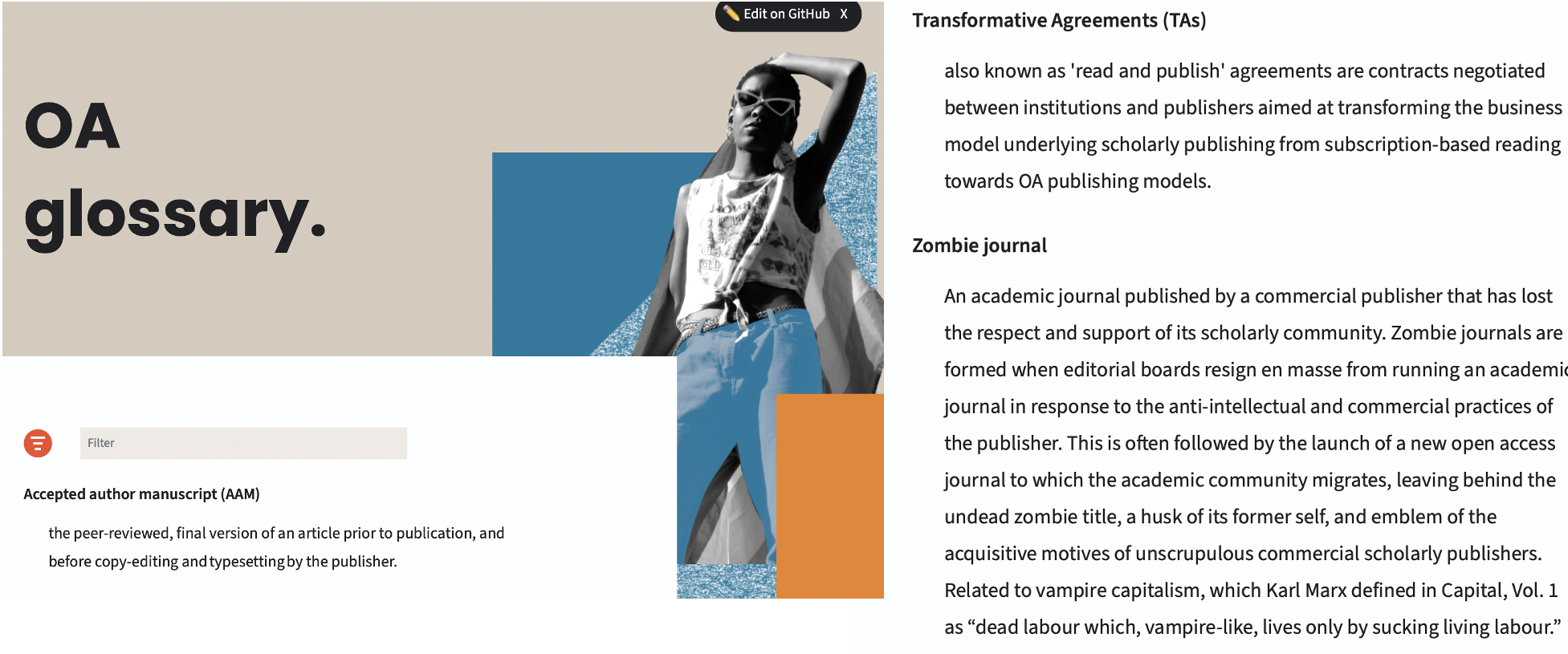

Knowing how difficult it can be to keep these fragile networks of activist knowledge alive, the least we can do at the OLH is update our Glossary with the term ‘zombie journal’. Even if wearing a zombie t-shirt is not your style, I implore you to update your own institutional glossary if you have one (you are welcome to borrow our wording).

Figure 2: updating the OLH Glossary

Just this small act of resistance could keep the term in wider circulation and help us see individual journal flips not just as backstage technical processes but part of a political movement. It helps us connect our open access work to the original vision of scholar-activists who dreamed of unrestricted online access to scholarly journals and articles, for the benefit of people over profit.

Call to arms

We are calling on our open access community. Help keep alive this story of rampant commercialism and the people who rallied together to prove that we are the scholarly community and that where there is community, there is life.

We need you to:

- Share and display the Zombie Poster.

- Print the poster, put it up on your office doors and anywhere editors will see it.

- Take a photo of the poster, use the #OAWeek hashtag and tag @openlibhums on social media to make sure we see and share your photos.

- Wear a t-shirt in the classroom, in the library, on your campus (you can order it here: https://chipsandgrady.uk/product/zombie-journals-tee-unisex/)

- If you have an open access glossary on your website, put in an entry for ‘zombie journal’ and share it widely.

We want to make sure that the term sticks. We encourage you to post them in what we are calling ‘jump-scare’ locations, where we can be sure they will register with their audience! We have commissioned a run of t-shirts featuring the artwork and are giving away one to the top poster location.

Finally, we are interested in publishing further research on the zombie journal phenomenon and wider malpractice within commercial publishers so that we can raise awareness amongst our research communities. If you would like to share information with us, anonymously or otherwise, please contact: r.harris-birtill@bbk.ac.uk

Happy Halloween, open access heroes!

This post was written by Dr Katherine Parker-Hay (Publishing Development Officer). Thanks to Dr Rose Harris-Birtill for research contributions, Dr Caroline Edwards for edits and the glossary definition and Andy Byers for help with the html mechanics underpinning this post. Gratitude to Johan Rooryck for agreeing to be interviewed and for sharing his story with the OLH.