Indian tech entrepreneur Kesavan Kandadai has many accomplishments under his belt: launching Amazon Prime Video in India and founding his own generative-AI startup, to name a couple. But at the age of 45, when people introduce him to a stranger, they always name-check his very earliest career achievement: graduating from Indian Institute of Technology Bombay.

“Even after 24 years,” Kandadai told Rest of World, “all the work I did, whether I had success or not, is secondary.”

IIT Bombay, in Mumbai, is one of India’s most prestigious higher education institutes. It’s one of the five original IIT engineering schools established in the 1950s and ’60s as the Indian government’s attempt to emulate the success of the United States’ Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Major expansions since 2008 have grown the system to 23 schools in total.

The IITs are now among the world’s top schools. Many young Indians apply for the entrance exams every year. Very few get in. In 2022, the IITs accepted just 1.83% of applicants, a rate more selective than that of U.S. Ivy League universities. The struggle to get into an IIT is so dramatic, Netflix has a multi-season scripted show, Kota Factory, about the country’s many prep schools that have sprung up to help coach applicants to pass the entrance exams.

Becoming an IIT one-percenter is often a ticket to tech success. Many big names in India’s startup scene are IIT alums. Of the country’s 108 unicorns, 68 were founded by at least one IIT graduate, according to data from analytics firm Tracxn.

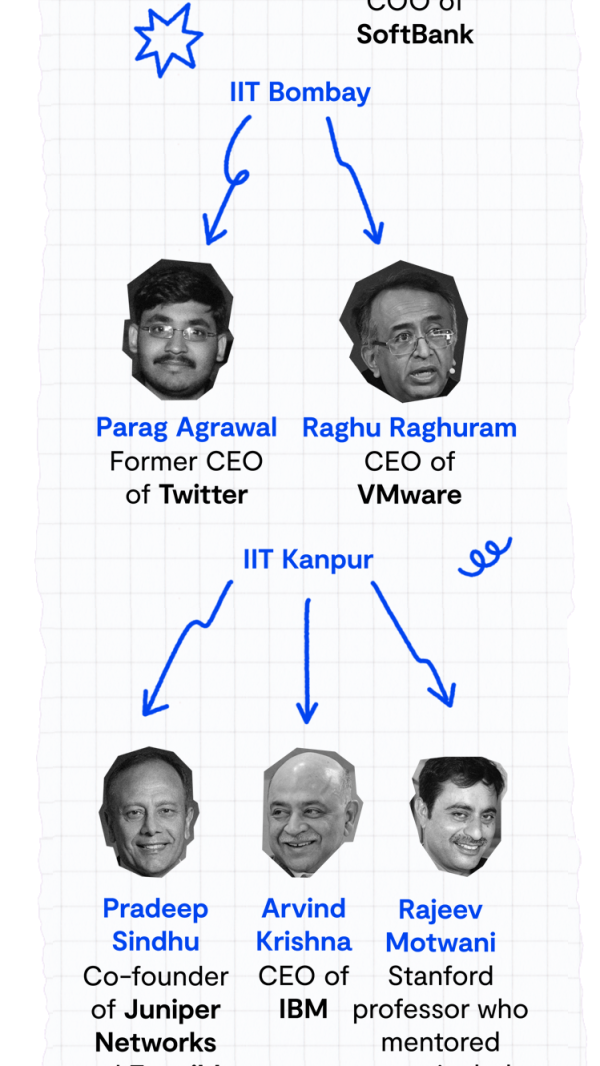

The schools’ influence expands abroad too. Some of Silicon Valley’s biggest companies are run by “IITians.” Google CEO Sundar Pichai said during a 2016 speech that going to IIT Kharagpur “changed the course of my life.” In 2005, the U.S. House of Representatives honored the graduates of IITs for their contribution to American society.

The IITs’ superpower is their tightly knit network of alums. Graduating from an IIT puts you in a special club. Rest of World spoke with IIT students, alums, and professors and discovered just how deeply embedded the schools’ network is in the tech ecosystems of India and beyond. At some companies, it’s IITians wherever you look. Founders, mentors, advisers? All IIT. The funders? Them too.

For alums, a resume adorned with an IIT degree opens doors that are harder to crack for graduates of other schools. Whether they are looking for a job in Bengaluru, an investor in Silicon Valley, or simply some career advice, IITians know who to call: each other.

IIT Kharagpur

- Founded: 1950 • Rank among Indian universities: 7 • Startup founder alums: 806 • Students claim their Spring Fest is the largest college festival in Asia.

IIT Bombay

- Founded: 1958 • Rank among Indian universities: 4 • Startup founder alums: 985 • Students also claim their Mood Indigo is the largest college festival in Asia.

- Sources:

IIT Bombay

Ministry of Education

Tracxn

Mood Indigo IIT Madras

- Founded: 1959 • Rank among Indian universities: 1 • Startup founder alums: 489 • An alum is the first female IIT director — at a new campus in Zanzibar, Tanzania.

- Sources:

IIT Madras

Ministry of Education

Tracxn

Mint IIT Kanpur

- Founded: 1959 • Rank among Indian universities: 5 • Startup founder alums: 605 • The Aerospace Engineering department has its own airstrip.

- Sources:

IIT Kanpur

Ministry of Education

Tracxn IIT Delhi

- Founded: 1961 • Rank among Indian universities: 3 • Startup founder alums: 1,054 • One campus building has a roof shaped like a hyperbolic paraboloid, a math concept.

- Sources:

IIT Delhi

Ministry of Education

Tracxn

The OG IITs

When Kandadai entered the IIT Bombay campus in the mid-’90s, it was the first time he’d laid eyes on a computer. Students learned how to code and read up on Silicon Valley, where tech companies were riding a wave of investment. It didn’t take long for Kandadai and his classmates to feel an entrepreneurial itch. “These were very early days of the internet, and there was a lot of hype around internet-based startups,” he said.

India’s tech boom was starting, and the IITs were at the center.

Back then, the school’s dorms did not offer much in the way of digital distraction. Instead, students discussed business ideas. Kandadai and three friends from the same dorm building came up with the concept for Albits, a startup for online events and trade shows. “We were among the few people who saw the opportunity of the internet and felt we could create something together,” he said. An investor, with whom they connected through an IIT professor, acquired the company after about 18 months.

After the dot-com bubble burst, students’ startup dreams briefly gave way to pragmatism. “Our goal was to get into [consultancy firm] McKinsey,” Zishaan Hayath, an angel investor who attended IIT Bombay in the early 2000s, told Rest of World. But tech’s appeal swiftly returned. Three years after graduating, Hayath launched Chaupaati Bazaar, a phone-based shopping startup.

Like many IITians, Hayath knew exactly where to turn when he wanted to kick-start his entrepreneurial dreams: the IIT’s alums network. He met his co-founder, serial entrepreneur Kashyap Deorah, at a reunion party. Deorah was already a big name in the IIT scene. During his senior year, between 1999 and 2000, he had founded blogging website RightHalf, the first startup to come out of IIT Bombay’s business incubator.

“You meet these incredible people, and eventually you start companies with them.”

“You meet these incredible people, and eventually you start companies with them,” Hayath said. “That’s the case with so many IITians, including me.” The first engineer he hired was Hemanth Goteti, a former IIT Bombay classmate.

Eventually, the Mumbai suburb Powai became a startup hotspot, earning it the nickname “Powai Valley.” Fast-growing companies — including real estate site Housing.com — hired dozens of IIT Bombay graduates; experienced entrepreneurs like Hayath mentored and funded young founders from the school.

Multiple founders told Rest of World that having an IIT background made it much easier for them to secure investment. “You’ll find your alumni everywhere. Some go to McKinsey, from McKinsey they go to [venture capital firm] Sequoia, from there you will meet someone for a pitch meeting, then sometimes they quit VC and start up,” said Hayath. “It’s an intermingling path.”

The IITs themselves have embraced their startup-spawning potential — there are currently 4,459 Indian startups that have at least one IIT-educated founder, according to Tracxn. Many of the schools run campus programs to foster entrepreneurship.

Prabhu Rajagopal, a professor at IIT Madras in Chennai, told Rest of World that until about 15 years ago, graduates felt that the education was “top notch” but too theoretical. “It was all class-based, equations, analysis — best training but very little practical execution,” he said. “So, many of our alumni got together and said, We should make a makerspace.”

The result is a “center for innovation,” which helps students with their projects. Those with commercial viability can join the institute’s “incubation cell” that provides free space and discounted legal, accounting, and back-end services. Since launching in 2013, the incubation cell has helped develop 325 startups, which have a cumulative valuation of about $4.9 billion.

One company epitomizes the power of the IIT alums’ effect like no other: e-commerce behemoth Flipkart, one of India’s biggest tech firms. Its founders, Binny Bansal and Sachin Bansal (no relation), were one year apart at IIT Delhi. They weren’t friends at school but connected after they both moved to Bengaluru for work and ended up in the same circle of people who had attended IITs. Flipkart and the Bansals declined to comment.

After they founded Flipkart in 2007, they hired many IIT alums. One early employee, Sujeet Kumar, had lived in the same dormitory building as Sachin Bansal. One day, Kumar told Rest of World, Bansal called him up to ask whether he’d like to join his book-selling startup. He went on to become Flipkart’s president of operations.

In turn, Kumar tapped his own IIT Delhi network to recruit more Flipkart employees. “The IIT connection helps us connect with the right people; it saves time,” said Kumar. “Some of the first critical people [at Flipkart] were from IIT.”

For Flipkart’s founders, their IIT backgrounds also helped secure early funding. IIT Kanpur graduate Abhishek Goyal was an associate at VC firm Accel in 2008 when he started hearing about the Bansals at parties in Bengaluru. “I had heard about them from my former colleagues at Amazon, that these two IIT Delhi graduates have started Amazon for India,” Goyal told Rest of World. “Everyone was talking about them.”

Goyal met the Bansals and was impressed. Their IIT backgrounds helped him make the case for investment. “It’s just easier to find reference checks, find common friends — so all of them help in scouting as well as building trust,” he said. Several months and meetings later, Accel invested $800,000 in the startup. “If someone comes with a large market, and they come from tier 1 schools, it’s easy to validate and back them,” said Goyal. “It’s not like good people don’t exist outside [of the IITs], but it’s just much harder to segregate.” (Goyal later launched Tracxn with another IIT alum. Both Bansals invested.)

The IIT connection also worked the other way, with prospective employees using their network to try to get a foot in the door. Around 2010, Ankit Nagori, an IIT Guwahati alum, worked his IIT connections to get in touch with Binny Bansal. He eventually became Flipkart’s chief business officer. “IITs have created a high density of people in different companies and roles, from the Bay Area to Bangalore,” Nagori told Rest of World. “So if you are from [an] IIT and called or wrote to any of these people, they will acknowledge and have a good conversation.” He added that while “the initial chunk of people were from IITs,” Flipkart became more diverse as it grew, “which was good for the company.”

While IITs are household names in India, their influence extends globally. During the 1980s and ’90s, when India’s own tech industry had yet to take off, IIT undergrads had one goal: pursue a master’s degree in the U.S. This included some of the biggest names in Silicon Valley today, such as Alphabet CEO Sundar Pichai and IBM’s chairman and CEO, Arvind Krishna.

Pichai attended IIT Kharagpur, where, like Kandadai, he had his first encounter with a computer. “I remember jumping onto a crowded train in Chennai and traveling for 24 hours to attend my school,” Pichai recalled at the 2016 Global Entrepreneurship Summit in California. “That opportunity changed the course of my life.”

Smeet Bhatt — IIT Bombay class of 2012 — has been in Silicon Valley since 2020, where he now runs his bitcoin startup Theya. He is part of a thriving community of IITians that connects over WhatsApp and Facebook or at special IIT events. “The IIT crowd is very very large and fairly concentrated in major companies and communities in [Silicon Valley],” he told Rest of World.

“That opportunity changed the course of my life.”

IIT Kharagpur alum Bidyut Parruck told Rest of World that when he moved to Silicon Valley three decades ago, it was almost impossible to stay connected with other IIT alums in the area. “There was no LinkedIn,” he recalled. In the 2000s, one local IITian published a directory of fellow graduates. “When I launched my startup [Azanda Network Devices] in 2000,” Parruck said, “I reached out and recruited one person [from that list], and then he brought his classmate, and soon we had, like, eight or 10 IITians in the company.”

Now, Parruck is president at IIT Startups, a nonprofit organization that provides young IIT alums in Silicon Valley and India with skills and connections. The organization relies on the IIT network to find speakers from around the world. “For instance, we had a mentor from the Philippines, a panel expert from the Middle East, and a panel expert from Germany,” said S. Muralidharan, a coach at the India chapter of IIT Startups, who is himself a class of 1981 IIT Kharagpur graduate.

IIT Startups’ ultimate goal is to make IITs collectively the largest unicorn producer in the world. “When we started, IITs were number four in creating unicorns,” Parruck said, without providing the figures behind his ranking. “Today, we are number three. We want them to be number one.”

An IIT education can set graduates up for much more than just their first job. Advaith Vishwanath, a graduate of IIT Bombay in 2014, shared how his IIT connections have been a continual source of support in his career to date.

When he graduated, Indian startups were on the ascendancy of a funding boom. That year, they raised $5.2 billion, according to YourStory. The next year, the publication calculated, they netted a record $9 billion. Noticing the money sloshing around, Vishwanath and five friends from campus launched Cityflo, a mobility app for office workers. “Starting up was definitely inspired by seeing a lot of our immediate seniors or peers starting up and getting capital,” he told Rest of World.

Vishwanath and his co-founders leaned on IIT Bombay alums to navigate the industry. “We knew one of the Housing.com founders pretty well,” said Vishwanath. “He would just tell us about small things that he had to deal with while fundraising and how we change our pitch accordingly.”

A few years later, when Vishwanath was ready to move on, he again turned to his alma mater’s alums network. All of the classmates he spoke with for career advice told him to go into venture capital. Being an IIT graduate came in handy there too. “One person from my college was definitely there at every [VC] fund,” he said. “Reaching out to these people is not that difficult.”

Vishwanath joined Accel as an analyst. His IIT connections helped him verify investment opportunities. “There are many companies that were started by folks within our peer group,” he said. “I could get a reference check easily. Sometimes I myself would know them.”

In 2019, Vishwanath quit Accel and co-founded his second startup, SuperShare, a content-sharing platform, with IIT Bombay friend Sagar Modi. In a way, his career has come full circle. Students now contact him. “I still get a lot of juniors from my college who reach out to me for tips because I used to work at venture capital,” he said. Everyone in the IIT community helps each other. “I take calls from people who I barely knew in college.”

There is a dark side to the IIT network. Not everyone feels like they’re part of the club. Students from minority groups in particular can feel like outsiders. Some students also struggle to cope with the academic pressures of both getting into an IIT and keeping on top of schoolwork once enrolled.

This is reflected most starkly in the IITs’ suicide crisis. Over the past five years, 33 IIT students have died by suicide. Many cases, news reports say, have been linked to caste discrimination.

In India, government-funded institutes like the IITs set aside a certain percentage of seats for people who are from historically oppressed castes. But many of the IITs don’t meet these quotas, and students from these minority groups face discrimination for being admitted through this system. One study of seven IITs between 2016 and 2021 found that more than 60% of students who dropped out were from “reserved categories,” which includes students from oppressed castes.

In 2021, a video of an IIT Kharagpur professor berating a group of underprivileged students was seen by many as indicative of how prevalent casteism remains at IITs. In an attempt to curb such issues, IIT Bombay last year introduced a mandatory caste awareness course and, last month, issued a directive that students cannot ask each other about their admission rank — a question that can identify people who were admitted because of their oppressed caste identity.

Women, too, have been — and still are — severely underrepresented at IITs. Anu Acharya, founder of DNA testing and fitness company Mapmygenome, remembers just 10 women in her first-year class of about 400 students at IIT Kharagpur in 1990. In some of her classes, she was the only woman.

Acharya told Rest of World that she didn’t find the experience detrimental, emphasizing that the tech industry is dominated by men as well. “In fact, it helps you in sort of going into the world much, much better prepared.”

But others felt the gender imbalance’s impact. In 2003, then 18-year-old Neha Singh followed her brother’s footsteps into IIT Bombay. She recalls her batch of about 500 students included only 30 women.

“Things have certainly changed.”

“It’s just something you’re not used to seeing in [elementary and high] school, and that suddenly changes, and you become a minority with a maximum of three to four females in most classes,” Singh, now co-founder of Tracxn, told Rest of World. “I realized afterwards that while there’s interaction amongst everyone, the men just knew a lot more people than some of the girls.”

Shruti, CEO of wholesale startup ApnaKlub, started at IIT Delhi in 2008 and said she was one of about 80 women in her 500-student third-year class. The campus was a place where she found friends, her spouse, and “massive growth” but also misogyny. “The spotlight on women on campus was evident from day one, and there were instances of gross apathy to how we felt,” Shruti, who goes by only her first name, told Rest of World. She recalled the first-year students’ magazine introducing new arrivals to “IIT Delhi lingo … one [item] of which was that ‘there are males on campus, and there are non-males on campus’ — and not girls.”

Both Singh and Acharya were quick to point out that IITs’ gender imbalance has improved in recent years. To encourage more girls to consider a future in engineering, the government’s council of IITs in 2018 set a quota for female applicants and reserved additional women-only admission slots. As a result, 20% of the first-year IIT students in 2022 were women, compared to 9% in 2017.

Prinal Kumat, currently a second-year student at IIT Madras, is never the only woman. “In every event we go [to], female participation [is high],” Kumat, 19, told Rest of World. Fourteen of the 70 students in her freshman batch were female, she said, adding that she considers it a step in the right direction. “The numbers should go up, but it’s decent right now.”

Acharya agrees. “When I went back to the campus recently for our 25th-year reunion, I saw a lot more women,” she said. “Things have certainly changed.”

Testing into an IIT remains the number one choice for Indians who want a career in tech. Every year anew, hundreds of thousands of Indians try but fail to get into the IITs. In 2018, 18-year-old Raghav Talwar was one of them. He said he’d prepared half-heartedly for the exam, and flunked it.

Then, in August of that year, Walmart acquired Flipkart for $16 billion, a record amount in Indian tech. Talwar was inspired. He read up on Flipkart’s founders and realized where his path to entrepreneurship would need to start.

“When I read about Sachin Bansal, I realized the role that the IIT had played in his journey,” Talwar, now 23, told Rest of World. “That was my motivation — I wanted to get into one of the old IITs, be around the smartest of the smart people, build a team and a venture.”

It was easier dreamt than done. Admission into an IIT requires taking the Joint Entrance Exam (JEE) Mains, scoring high enough to be allowed to take the JEE Advanced, and scoring high enough again to be given a spot at one of the 23 IITs. The original five schools — Kharagpur, Bombay, Madras, Kanpur, and Delhi — are still considered the best and are the hardest to get into.

To beat the odds, Talwar entered India’s vast ecosystem of test prep schools — some of these are so competitive, they have entrance exams of their own. He spent long hours every day studying in preparation for the JEEs.

This time, Talwar did much better. He ended up getting assigned to IIT Madras, which he had ranked as his third preference behind Bombay and Delhi, becoming the first person in his family to attend a prestigious engineering institute.

While on campus, Talwar realized how different studying at an IIT was compared to the studying he had done to get in. “When you are in the coaching phase, it’s very linear — you have to study and secure as many marks as possible,” he said. “But on campus, your success can be multidimensional and not just academic.”

After his second year, Talwar came up with a fintech startup idea: a platform allowing retail derivatives traders to automate their trading strategy. He joined the campus entrepreneurship cell and waded into the IIT network. “[There are] so many role models to interact with and learn from,” he said.

“I am now looking for a co-founder to take this company forward,” said Talwar, who graduated this summer. He is talking to two potential candidates — both from IITs.

In India, suicide prevention organization Aasra can be reached at +91-98204-66726 or at these local numbers. In the U.S., the Suicide & Crisis Lifeline can be reached by dialing 988. A longer list of helplines by country is available.