Abstract

In this paper, we investigate how highly ranked business schools construct their legitimacy claims by analysing their online organisational communication. We argue that in the case of higher education institutions in general, and business schools in particular, the discursive formation of these legitimacy claims is strongly connected to the future. Consequently, we utilise corpus-based discourse analysis of highly ranked business schools’ website communication by focusing on sentences containing the expression ‘future’. At first, we analysed the future-related language use to reveal the general future picture in the corpus. Furthermore, by combining qualitative and quantitative textual data, we identified six typical agency frames (i.e. preparing, shaping, adjusting, exploring, personal future, responsibility) about the future. By examining the co-occurrence of these frames, we were able to identify different discursive strategies. As we connected our findings to general societal phenomena we could interpret why and how business schools utilise these discursive strategies to (re)create and maintain their legitimacy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

All social organisations have implicitly or explicitly stated reasons about why they exist and why do they operate in a certain manner (Bronn and Vidaver-Cohen 2009). Finding the ‘right’ reasons and publicly stating them can be understood as the process of claiming organisational legitimacy (Suddaby et al. 2017). This is not a trivial matter since losing legitimacy can mean losing social support, social trust, and in turn, resources essential for operation (Deephouse et al. 2017). Therefore, organisations strive to maintain their legitimacy and find new legitimacy claims when old ones are no longer applicable in changing social contexts.

As far as business schools as organisations are concerned, the issue of legitimacy is particularly pertinent since they are under heavy criticism in relation to the (ir)responsibility they inculcate in their graduates, as well as to the role they play in shaping current and future economic realities (Miotto et al. 2020). One of the main criticisms towards them is that they encourage students’ ‘profit first’ and opportunistic mentality (Ghoshal 2005). This outlook posits shareholder value as a top priority even above societal well-being and takes market logic as the primary social and coordination mechanism. In this manner, business schools are held responsible for the frequent ethical scandals in the business environment (Beusch 2014).

Furthermore, they are often invoked as the very actors who train students for participating and maintaining managerial capitalism. This socio-economic order led to the market failures and the financial crises of the last decades (Murcia et al. 2018), as well as the overconsumption and degradation of natural resources. These raise the question of responsibility in relation to post-crisis business education. Given the widespread and all-encompassing nature of these critical arguments, business schools are under pressure to construct legitimacy claims maintaining, or even redefining their social acceptance (Miotto et al. 2020).

In this paper, we argue that business schools’ legitimacy-construction is tied to the future. In other words, they have to explicitly propose answers to the challenges the future holds. These answers are twofold, on the one hand business schools provide a ‘future-picture’ in their communication, and on the other hand they often appear as agents who do something (such as prepare, explore, shape) with the future.

In relation to the above-mentioned arguments, this paper attempts to answer the question of what kinds of linguistic tools and discursive elements business schools utilise in relation to the future to construct and (re)claim their legitimacy. This research question is connected to the academic discourse which investigates the external communication of higher education institutions (henceforth HEIs) to grasp sectorial and organisational characteristics, and strategical priorities (e.g., Bayrak 2020; Huisman and Mampaey 2018).

This paper contributes to the existing literature in so far as it presents an analysis of the external online communication of the 100 highly ranked universities’ business schools and economics departments (Times Higher Education (THE) list, see below). It extensively examines the language use and discursive strategies of business schools related to the conception of future on a large corpus, which is unprecedented to our best knowledge. Moreover, it also offers fresh methodological insights since it presents a corpus-based analysis of online texts in a mixed methodological framework.

As far as the structure of the paper is concerned, the ‘Conceptual frame: legitimacy and organisational discourse’ presents the conceptual background of our research, which is followed by a brief overview of empirical research results about HEIs’ communication. The ‘Research studies on HEIs’ external communication’ of the paper discusses the data-gathering and analytical process in detail followed by the results of our analysis. In the final, ‘Discussion: discursive legitimacy construction strategies’, we interpret the results by positioning them in a broader social context.

Conceptual frame: legitimacy and organisational discourse

HEIs can be seen as organisational actors, who strategically and deliberately choose their own actions to reach their predefined goals (Krücken and Meier 2006). Accordingly, their actions and performance could be measured and scrutinised, and they can be held responsible for their choices and actions. In this sense, these organisations can be understood as open organisations (Scott 2003), that is, entities that are in continuous interaction with processes, demands and changes of their environment. Conceptualising HEIs as open organisations also points to the fact that legitimacy and social acceptance is the key for their operation (Bronn and Vidaver-Cohen 2009).

Legitimacy is a complex concept, which can be viewed from different perspectives. Following Suddaby and his colleagues’ synthesis of the phenomenon (Suddaby et al. 2017), we could approach legitimacy from three different angles: as a property, as a process, or as a perception.

The legitimacy as a property concept focuses on the organisation itself and defines legitimacy as its inherent attribute. Accordingly, legitimacy is viewed as a (level of) ‘fit’ between the organisation and the expectations of its environment. As Suchman (1995) conceptualised, legitimacy is a socially constructed and perceived compatibility between the given organisation and its environment providing normative frameworks for its operation.

The legitimacy as process approach, however, directs our focus on those interactive processes which provide legitimacy that is those meaning-making procedures of social construction which contribute to the collective acceptance of a social entity (Suddaby et al. 2017). According to this interpretation, organisations possess a high level of agency in forming their interactions and pursuing their goals. Consequently, the role of language and communication is central to this approach.

Contrary, the legitimacy as perception strand of theory is focusing on the audience, that is, on the individual evaluators, who lend legitimacy to the organisation by accepting it. This version of the concept concentrates mainly on the micro-level, namely, on the perceptions of individuals. However, individual evaluations are eventually aggregated to a collective validity at the macro-level.

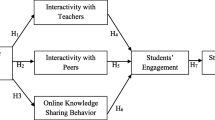

The schematized model of these legitimacy conceptions and their application to our research topic, i.e. business higher education can be seen in Fig. 6. As illustrated, the central actors of our research are business schools. They actively shape their external communication to address prospective students, as well as their parents (as individual evaluators), and to address the general social environment, such as other business schools, governance, and the general public (as social validators). In this sense, they are active agents forming their messages about their goals, roles and importance in society. In line with this, in our understanding, legitimacy is a constant process, a highly interactive ongoing ‘project’ for achieving social and individual acceptance.

This interactive character and the strategic language use points to the discursive feature of the legitimacy processes (Grant et al. 2004; Phillips et al. 2004). Discourse analysis (DA) and its theoretical framework can capture the connection between action and discourse, the role of texts and communication (Fairclough 2003; van Dijk 2007). As Phillips and Malhotra (2008) stated ‘individual actors affect the discursive realm through the production of texts. (…) In turn, discourse provide the socially constituted, self-regulating mechanisms, that enact institutions and shape the actions that lead to the production of more texts’ (p. 713–714.). That is, the website text of a given business school contributes to the general discourse about the role and responsibility of business schools, and at the same time, is constrained by that general discourse provided the other actors of the field.

Accordingly, business schools have to adjust their communication to the frames of the general discourse, but at the same time, there is space for manoeuvring in this regard. This is also related to the so-called uniqueness paradox, when an organisation has to be similar to the other actors of the field in order to be considered as a legitimate participant, while it should also be different to justify its existence as a separate and unique entity. As we can see, both of these sides are closely connected to processes of legitimation (Suddaby et al. 2017, p. 461).

Discourse analysis can capture this duality, because its interpretive approach focuses on the role of language in meaning-making processes at a societal level by uncovering frames of references utilised by the actors involved. This approach attempts to identify discursive patterns and structures in large corpora of texts (Heracleous 2006). At the same time, DA can be used to analyse the intentional nature of language use, focusing on how language can be effectively used to reach desired organisational results. Consequently, DA accentuates the goal-oriented aspect of language-use (see example on rhetorical strategies at Suddaby and Greenwood 2005; or discursive strategies at Vaara and Tienari 2008).

This strategical language-use gains a special importance in cases when the organisation is challenged by internal or external actors. This can be interpreted as a special ‘responding scenario’, as Deephouse and his colleagues label it (Deephouse et al. 2017): there is a challenge regarding the legitimacy of the institution, therefore, an immediate response is needed, which could reassure the audience and evaluators about the appropriateness of its performance and values. As we introduced it earlier, there is a growing criticism towards business schools related to recent financial crises and environmental degradation. One of the platforms which could provide reassurance to stakeholders is the website of these organisations where they can reinforce their importance, effectiveness, social role and responsibility. Therefore, we strived to compile a large corpus of website texts of business schools for our research.

A useful token to (re)build legitimacy could be a reference to the future. An institution’s future-oriented discourse (or anticipatory discourse) can contribute to their discursive legitimisation in two ways (Bondi 2016). Firstly, regarding their knowledge on future (de Saint-Georges, 2012) with the help of ‘futurological predictions’ the institution equips themselves with the social power and the expert authority of predicting what the future holds, as if they had factual knowledge of things that have not yet happened. This ‘knowledge’ makes them seem socially indispensable (Fairclough 2003). Moreover, through these authoritative predictions the institutions can legitimate certain actions in the present (Fuoli 2012; Oddo 2013). Secondly, regarding their agency concerning the future (de Saint-Georges, 2012) with future-oriented commissive statements the institutions show their ‘commitment to future action or conduct’ (Yu and Bondi 2019).

Projecting the findings of political discourse analysis (Fairclough 2003; Oddo 2013) and CSR analysis (Bondi 2016; Fuoli 2012; Yu and Bondi 2019) in futurity discourse to higher education discourse, we assume that HEIs use future-oriented discourse to legitimise themselves since they imply and self-evidently state their future existence both in the use of future-knowledge and future-oriented commissive statements. That is, by taking for granted their agentic role in the future, business schools claim their social importance and hence legitimise themselves. Consequently, we investigate how business school create agency (van Leeuwen 2008), how they construct their role and responsibility in shaping or adapting to a perceived future.

Research studies on HEIs’ external communication

Examining the academic literature on higher education, we can see the constant presence of studies concerning HEIs’ external communication. Most of these articles deal with issues such as organisational identity, branding and the connected stakeholder expectations. Accordingly, they analyse communication materials and texts which are generally about the purpose and values of HEIs, that is, missions, visions or welcome speeches (Morphew and Hartley 2006; Özdem 2011; Sauntson and Morrish 2011). By examining the content of these texts, researchers are able to identify the most important ‘messages’ signalled by the organisations. For example, when Huisman and Mampaey (2018) investigated the welcome addresses of 29 UK universities, they identified 21 categories related to research activity, education and third mission.

The most prominent theme of this literature is the dichotomy of sameness and difference (Huisman and Mampaey 2016; Kosmützky and Krücken 2015). This overarching issue refers to the inherent dilemma regarding the strong isomorphic forces of the field (especially by mimicking the leading institutions) and the unique-selling-point logic of ‘branding’ (as the ‘uniqueness paradox’ captures it — see above). Kosmützky and Krücken (2015) emphasise that the similarity aspect stems from the shared institutional purpose of HEIs. Nonetheless, there are organisational specificities leading to differences. The sources of these according to the literature are typically the age of institutions (Huisman and Mampaey 2016), the subject of education (Kosmützky and Krücken 2015), the institutional type (Morphew and Hartley 2006) or some measurement of prestige or ranking (Blanco and Metcalfe 2020).

These similarities and differences are typically analysed in national contexts (like UK in case of Huisman and Mampaey 2016, 2018; Turkey in Özdem 2011 and in Efe and Ozer 2015; Germany at Kosmützky and Krücken 2015, or USA at Blanco and Metcalfe 2020). However, there are a few cases of international comparisons. Bayrak (2020) for example based his selection of international HEIs on the THE ranking and chose region as the main dimension of his comparison.

Apart from the relative lack of international comparisons, another blind spot of the literature is research on business schools. Most research projects investigate universities and/or colleges in general with a national coverage. While HE is undeniably a highly diverse field, subject- or sector-related analyses are quite rare. An interesting exception is the paper of Palmer and Short (2008) focusing on US-based business schools. In this study, they collected mission statements from 408 AACSB (Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business) schools and examined the relations between the content of these statements and the performance of the schools.

As far as methodological issues are concerned, the applied method in these papers is typically (content-based) qualitative or quantitative thematic analysis. However, there are a few examples of discourse analysis in the field (see Fairclough 1993). For instance, Efe and Ozer (2015) used corpus-based discourse analysis to analyse the vision and mission statements of universities in Turkey. They focused on discursive strategies to understand how social actors and their actions are represented. Ford and Cate (2020) analysed the discursive construction of international students on US university websites, focusing on how they are framed as ‘markers of prestige and legitimacy as well as a means of economic stimulus’ (Ford and Cate 2020, p. 1196).

In summary, we can state that the practice of using organisational texts as relevant data plays an important role in the academic literature on HE. However, business schools as a sector and their discourses are somewhat under researched in this field. This study aims to provide new insights regarding this research gap by examining highly ranked business schools’ discourses. We are aware that rankings cannot be considered objective measures of quality (Bougnol and Dulá, 2015), and their use is constantly contested (Barron 2017); however, we have to acknowledge the fact that rankings are influential in many key decisions in HE, including funding, and choices of students and academics (Bowman and Bastedo 2011).

Methodology

Sample and data collection

The THE World University Ranking lists universities from all over the world and is not only an important source of data for prospective students and their parents but also a frequently cited sign of high-quality education by HEIs themselves (Blanco and Metcalfe 2020). Besides the main World University Ranking, THE makes sub-rankings by subjects, out of which we focused on the ‘business and economics’ list.

The source of our data collection was the website of each university’s business and economy school/department.Footnote 1 Specifically, those pages of the websites that present the school/department to the general public (i.e. the’About us’ sections). We imported the downloaded data to R, where sentences containing some form of the word ‘future’ were selected, resulting in 376 units that constitute our corpus.

Analysis and interpretation

As the first step of the mixed methodological approach (Fig. 1), we carried out some quantitative analyses that generated descriptive data. In this phase we analysed the distribution of the expression ‘future’ (and its related forms) in the corpus and its association with universities’ geographical location.

Our qualitative lexical analyses at first focused on the grammatical and lexical structure of each unit. This process highlighted the role that the expression ‘future’ plays in the analysed sentences and the words accompanying it.

Next, we moved on to the discourse analysis of the texts. The methods applied are based on the methodological propositions of Gee (2011) and Tonkiss (2012). The first discourse analysis phase focused on the textual construction of the social context of ‘future’. That is, we analysed the scope to which ‘future’ referred to explicitly or implicitly. By doing so, three levels were distinguished: individual level, community level, and social/global level. This analysis highlighted the specific societal levels on which the HEI’s discursively constructed the future.

In the next phase, we analysed agency regarding the future. Founding our methods in interpretive discourse theory (Heracleous 2006), we aimed to analyse whether future is framed as something that can be shaped, or as a phenomenon that shapes the world around itself. In other words, we wanted to know who has agency in the practices and activities that occur in our corpus (Gee 2011; Tonkiss 2012). As the units of analysis were the sole sentences that contain the expression ‘future’, the analysis was content based. Through this inductive, data-driven approach, we sorted the units into at least one of the following categories (agency frames): preparing, shaping, adjusting, exploring, personal future, (social) responsibility. Agency frames in this analysis are not exclusive, meaning that one unit can contain the characteristics of different portrayal techniques. These frameworks highlight the techniques of future representation and; thus, the modes of the discursive construction of future in university texts.

As our last step, we carried out a quantitative analysis based on the defined frames (Géring 2021). In this, units were analysed individually and per institution, to see if there are correlations in the occurrence of different frames.

Finally, we would like to reflect on the shortcomings of this research in order to help interpret and put in context our findings. Firstly, as the consequence of our corpus-based approach (Baker et al. 2008), the analysis is based solely on these units that is those sentences where the word ‘future’ (or its different forms) appeared. This affects the interpretation of the results: the findings can only speak for the business schools’ future portrayal, and in no way are reflective of the entire universities’ communication. Moreover, one should keep in mind, that the corpus reflects only the explicit future-related discourse, and furthermore represents a snapshot in time, as the websites can be changed relatively easily and often. We also would like to emphasise that the qualitative analyses are based on the researchers’ interpretations, as words and sentences do not have inherent meanings, but are understood through the personal and social processes of meaning-making (Gee 2011).

Findings

In the following subsections, we aim to show how business schools use language strategically in order to make future-related legitimacy claims. The order of these subsections moves from basic linguistic building blocks to more complex forms illustrating the full repertoire of discursive strategies.

Descriptive statistics of studied HEI’s

Out of the highly ranked 100 business schools, 89 have ‘future’ expressions in their texts. These schools are from four continents distributed as shown in Table 1. As we can see these ratios are not significantly different from the general regional distribution of all the schools. In other words, regionality does not contain information on institutions tendency to utilise the expression ‘future’.

Word-level analysis: the role of the expression ‘future’ and associated phrases

At first, we shall present some basic descriptive data regarding immediate context of the word ‘future’ by showing the frequency and attributes of the different grammatical functions it plays.

As for the attributive adjectives (i.e. what kind of future) associated with the word ‘future’, we can see (Fig. 2) that mostly positive expressions are attached to it, like ‘better’ and ‘brighter’ futures (40%) or ‘responsible’ and ‘sustainable’ futures (37%). Even the least positive expressions are conveying only mild disconcert when they refer not to strong negative feeling but only to uncertainty (23%). This general positive tone could be attributed to the genre, that is, organisational image texts are generally positive or neutral in their manner.

As for possessive phrases (such as pronouns and determiners, i.e. somebody’s future or the future of something), it can be seen in Fig. 3 that the most often applied possessive compound together with ‘future’ contains ‘your’ (26%), closely followed by ‘business’ (25%). The use of expressions such as ‘their’ and ‘our’ are much less frequent (10–10%).

If we examine the expressions (n = 188) where future is the qualification of something (i.e. future something), we can see that expressions about leaders represent the largest category with 39% (Fig. 4). The ‘leaders’ category is followed by a group containing abstract and cognitive entities such as future visions, values and opportunities with 17%. The third largest group of sentences (14%) contain compounds regarding education and students.

These word-level attributes show how ‘future’ can be used to create positive connotations and meaning in different ways even in the simplest semantic level. However, if we move to a more complex level, we can detect more complex language-use and discursive strategies.

Content-based analysis

Societal levels referred to in the sentences containing ‘future’ expressions

By moving from the word-level to the content-based analysis, at first, we coded the data — that is the sentences containing future-expressions — in connection with the societal levels they refer to. By doing so, we distinguished sentences referring to individual, community or social/global levels. Units not specifying the extent of future influence were not coded in this aspect (i.e. very short mottos). As for the individual level, most often these sentences were about the personal future of the students (e.g. your own future). We coded to the community level all those sentences which invoked a common, shared future (e.g. our future), referred to organisations (e.g. future-focused business school) or to a specific community of people (e.g. future business leaders). Lastly, we assigned those sentences to the category of social level which referred to a particular industry or field (e.g. future business), to a specific country or nation (i.e. the future of Korea) or to the global level (e.g. global economy).

Regarding the general distribution of these categories, Table 2 shows that the slight majority (51%) of sentences imply future at the community level, while the second biggest category is the social level with 33%. It might be surprising that the individual level is the least utilised category (16%) in terms of institutional communication about the future.

We can also investigate the data in regional distribution (Table 2). As the table shows, the sentences stemming from Australian institutions deviate the most from the general proportions; however, this might be due to a bias caused by the low number of sentences from Australian institutions (nAus = 25) in the sample. As for the sentences of Western European institutions (nWEur = 115), the individual level category is more strongly represented with 21.7% than in the general data. The communication of the North American institutions largely corresponds to the general proportions between levels, which is understandable given that most of the sentences in the sample belong to this region (nNAmer = 183). It is interesting to see that while both societies in Western Europe and North America can be characterised with an individualised value system, the individual level is more prevalent in Western European than in North American institutional communication. Lastly, we can see that the East Asian institutions (nEAsia = 53) considerably differ from the general pattern. The individual level is relatively missing from the institutional communication about the future, while the community and social level is almost equally represented. While this is interesting, it is also in accordance with our expectations given East Asian countries’ more collectivistic value systems.

These results lead us to the next topic that is the question of agency behind these patterns of future-related language use.

The identified agency frames

To capture the diverse agency patterns in the future-related communication of business schools, we identified 6 frames in the corpus: preparing, shaping, adapting, exploring, personal future, (social) responsibility.

We coded sentences as ‘preparing’ if they state that somebody/something can be prepared for the future. In these, future is something that happens to mankind and for which the students, the future leaders or the business can and/or should get ready for. In this regard, business schools claim to have the agency to prepare them. In our analysis, words and phrases like ‘provide [skills or knowledge]’, ‘prepare’, ‘to help [develop]’, ‘to create [leaders, role models, etc.]’ and ‘to train’ indicate this frame.

‘Shaping’ sentences focus on the ability of affecting the future. In such sentences, either the schools or the students have agency over the future. The latter instance consists of sentences that explicitly assign agency to students and of sentences implying that the students’ agency is achieved through participating in the educational programme. The analysis focused on processes and activities in the sentences that suggested that the future can be changed. ‘Shaping’, ‘changing’, ‘impacting’, ‘building’, ‘powering’ and ‘supporting’ are just a few processes through which the school or its students are to achieve a change.

‘Adapting’ framing of the future refers to sentences in which it is suggested that the future is inevitable and the students, leaders, schools, industry, etc. will or already have to adapt to it.Footnote 2 In these units, actors in connection with the business schools do not have agency over the future, their processes and activities imply a future independent of human intervention.

In several cases, the schools frame the future as something to be explored either by them, or by their students. Units that are coded as exploring suggest that the future is yet uncharted and the institutions and/or their students agency extends to the point of being motivated and brave enough to delve into it. Processes and activities in this category are frequently phrased as ‘explore’, ‘discover’, ‘[unknown] future opportunities’, ‘[unknown] future challenges’ and always tackle the topic of discovering the unknown future.

Personal future as the framing of agency appeared in the units through promises and possibilities in connection with the students’ own future. In these sentences, the business schools pledge they can help their students’ future: by teaching them how to shape it, helping them in discovering, adjusting or preparing them for it. The key is that they all represent future-related agency on a personal level. Although the sentences concern the personal future of the students/leaders/etc., institutions are sometimes portrayed as the active agency behind them.

Business schools put great emphasis on (social) responsibility in their future corpus. In such sentences, the schools and/or the future leaders (aka. students) have agency in creating a sustainable, more equal future with responsible leaders. Most of the institutions focus on either the representation of their own efforts or their goal of providing an education that emphasises the importance of responsibility.

The figure below shows the distribution of agency frames. Nevertheless, one has to keep in mind that they are not mutually exclusive categories; that is, one sentence can belong to more than one frame (Fig. 5).

Looking at the data (Fig. 5), it can be stated that almost half of the sentences (48%) portray future as something one can be prepared for. Business schools find it important to emphasise that they can prepare, train, develop the leaders of the future. Another conclusion is that in the future discourse of business schools, future is rather shapable (30%), and less of a phenomenon that one adapts to (7%). Responsibility appears at this level of analysis, in more than a fifth of the sentences (21%). It seems that the remaining frames that is exploring (19%) and personal futures (17%) are less characteristic to the discourse, yet some institutions still utilise them to express their relation to the future.

Co-occurrence of frames

The distribution of agency frames exhibit co-occurrence patterns within schools, which means that if a certain frame or a collection of frames are used by an institution then some other frames are significantly more likely to be included than pure chance. To discover these patterns, the classical association rules mining technique was used (Agrawal and Srikant 1994), in which business schools are the agents selecting frames to include in their texts.

The rules are stated as associations between two parts comprised of frames, the left-hand side (LHS) and the right-hand side (RHS), which can be considered as the two parts in an if–then clause (with some probability). Significance was determined by a chi-squared test for probability of the frames in both the LHS and the RHS present for a HEI compared to the probability of these two being independent. Table 3 shows the significant rules with their statistics ordered according to ‘lift’ as that can be interpreted as the strength of a rule.Footnote 3

As it can be seen, the significant co-occurrences can be divided into two groups. The first group of rules (Rule ID: A, B, C) states that if a business school included some combination of the frames ‘preparing’, ‘exploring’, and ‘personal future’ in its text, then ‘adapting’ is more than two-times more likely to appear than by chance. That is, the frames in these three rules invoke a discursive strategy, which seems to focus on the individual and portray the future as something that the person prepares for and explores to be able to adapt when needed. Thus, the agent is only reactive to some unknown future which may not be altered.

However, the other group of the rules (from D to I) paint a different picture. As it can be seen in Table 3, in these frame-combinations ‘adapting’ is completely missing, and all of they are connected to ‘shaping’ and ‘responsibility’. In this sense, this group of significant rules (frame-combinations) can be understood as a different discursive strategy, which shift the emphasis from the individual and deterministic future to the community or social level and a future that can be shaped. Here, the agent needs to prepare themselves and assume responsibility in shaping the future.

Discussion: discursive legitimacy construction strategies

In the following, we shall discuss the interpretations of our findings regarding the representation of future in business schools’ external online communication. The results are reviewed through three identified modes of legitimacy strengthening organisational communication: the generated future-picture, the applied discursive strategies and specific organisational communication regarding sameness and differences.

Positive future-picture as strategic language use

The analysed language-use underpins the legitimacy claims of business schools. As it mirrors the principles of organisational communication, it is supposed to strengthen the organisations’ legitimacy and social acceptance that is vital for their operation (Bronn and Vidaver-Cohen 2009). Our corpus fits strategic organisational communication in that it is written in a rather positive tone, both in wording and in explicit and implicit content.

It is clear not only from the list of adjectives future is associated with, but from the identified agency frames as well, that a hopeful and progressive visions dominate the representation of future. That is, the future is bright and better or, in the ‘worst case scenario’, it is unknown (yet), so it can be explored. This positive future-picture with positive agency frames is not surprising in itself, however, as a strategic choice not only invokes positive emotions in the reader but also provide an action set (shape, prepare, explore, responsibility etc.), which indicate active and responsible behaviour from the business schools. Nevertheless, both the positive future portrayal and the provided action set imply the schools’ legitimacy in the present and the future. On the one hand, overwhelmingly positive statements regarding the future can be interpreted as ‘futurological predictions’ that represent the institutions as experts with exact knowledge on the nature of future (de Saint-Georges, 2012), hence posing as socially essential sources of knowledge about the future. On the other hand, presenting an action set ‘reveals how empowered that speaker feels to act and affect situations to come’ (de Saint-Georges, 2012:2), while commissive statements with aforementioned action sets show the institutions’ commitment to future action (Yu and Bondi 2019). Understandably, business schools will not communicate about doom and collapse (even if these are also part of the future-related archetypes, see Fergnani and Jackson 2019). However, presenting such a one-sided image of the future almost as a fact leaves very limited space for reflexivity and self-criticism.

Social role-related and action-related discursive strategies of legitimacy

If we look at the co-occurrences of the identified agency frames, we can see that legitimacy claims are embodied through different discursive strategies. On the one hand, business schools argue for their important role in society by emphasising either the (social) responsibilities they take on or their role in preparing students for their personal future (social role-related discursive strategies). On the other hand, the future-related discourse about their actions seems to be built around two building blocks: either shaping the future or adapting to it (action-related discursive strategies).

Turning our attention towards the social role-related discursive strategies, we can see two discursive tokens around which the discursive strategies are built: (social) responsibility and personal future. As our findings showed, responsibility appeared both in word-level analysis and in agency frame analysis. We suspect that this is — at least partly — the business schools’ answer to the criticism towards them. The global financial crisis in the late 2000s shook the trust in the so-called Western economic systems. At the same time, a significant portion of society lost its faith in the business leaders who were meant to control the system that failed (Murcia et al. 2018). Moreover, after the crash, business schools continued to teach mainstream economics underlying managerial capitalism that led to the crisis in the first place. Criticism regarding the operation of these schools emerged both in the public and the scientific discourse (e.g., Miotto et al. 2020; Parker 2018). The schools in order to keep their prestige and good social standing have to response to these challenges (Deephouse et al. 2017). Accordingly, they should put more emphasis on social responsibility, teaching students the bases of ethical economic thinking and other social matters, too, like environmental and minority issues. Furthermore, based on the co-occurrence of the agency frames, it is clear that the responsibility frame is mainly connected to the ‘shaping’ and ‘preparing’ frames; that is, it appears in a very active action set indicating changing and readiness towards the future.

One more reason for universities to discursively reinforce their legitimacy is the general decline of trust in their competency regarding useful knowledge transfer (Király and Géring 2019). An ongoing debate appears frequently in the public discourse on the raison d'être of traditional HEIs, one side claiming that they are not capable of teaching useful skills but focus too much on theoretical knowledge, which the students can hardly apply later (Király and Géring 2021). The analysed business schools seem to have two strategies to regain the public’s trust in this matter. First is by framing the institutions as places where the future leaders will learn how to shape and change the future (see below). Second is by putting great emphasis on preparing students for their own future: 38% of the units engaging in the agency frame ‘personal future’ also employ the ‘prepare’ frame. Hence, the external online communication delineates an organisational environment that encourages students to achieve their future goals, in becoming successful and productive members of the society. This way anchoring and legitimising their importance and role in society by using students’ personal future agency frame.

Regarding the action-related discursive strategies, a discursive pattern which can be interpreted as an attempt at strengthening business schools’ legitimacy is the recurring representation of future as something that can be shaped. In engaging in this discursive strategy, the institutions claim legitimacy through empowering themselves (or their students) to be the actors who are in the know about the future, and also the ones who can ‘act and affect the situations to come’ (de Saint-Georges, 2012:2). The prevalence of this strategy was underpinned both by word-level analysis and the agency frame analysis. In such units, actors who shape the future are mostly the institutions and the students (‘future leaders’) with the contribution of the schools, through, e.g. teaching, preparing and training. Therefore, future change is tied to the business schools both directly and indirectly. As already mentioned, there are some critical voices towards business schools and the last global economic crisis battered their reputation. One possible way to restore the social faith in them is to represent themselves as active shapers of the future economy, as they could prevent such a crisis from happening again. This, again, is a legitimising gesture, as they argue for their current decisions and existence based on prognoses about the future (Fuoli 2012), namely that their changed education can lead to a sustainable and responsible economic future — of which they cannot have knowledge of, only hypotheses.

Another action-related discursive strategy is connected to the ‘adapting’ agency frame, which invokes less active actions in relation to future; however, it emphasises that even if the future is not changeable, business schools have the necessary knowledge and capacity either to adapt to it (and its challenges), or help their students to adjust to it. Hence, they invoke legitimacy by claiming to help their students adapt to the future, which implies that they are the experts to make futurological predictions and determine what and how to adapt to. Although this frame is the least frequent among the identified agency frames, it is playing a significant role in shaping the discursive strategies, because it appears typically with the ‘personal future’ frame (but not with social responsibility). Furthermore, even if adaptation could be seen as a rather passive attribute, it is mainly occurred with preparation and exploration, that is, it invokes active actions, even if they are much more cautious and avoid interfering with the future.

The sameness-difference dimension of organisational communication

As we saw both in the conceptual frame and in the academic literature, an often recurring theme in HEIs organisational communication is the question of sameness and difference. This topic may be interpreted as means of legitimacy through the ‘uniqueness paradox’ that pressures the institutions to produce similar texts as other actors in the same field in order to seem legitimate actors; nevertheless, it also demands the organisations to justify their existence through emphasising their uniqueness (Suddaby et al. 2017). Our findings underpin the notion that universities intend to produce self-representational content that is similar to each other as it strengthens their legitimacy discursively. In our analysis, the overarching positive tone of the utterances is evident, just as the application of the six identified agency frames.

However, as the paradox highlights, the HEIs are interested in creating original texts as well, to distinct themselves from other institutions and thus validate themselves as a separate entity (Krücken and Meier 2006). In this case, the differentiation was embodied in the distinct discursive strategies focusing on individual/personal future or on community/social responsibility.

Focusing further on divergence, cross analysis revealed that the business schools’ geographical location also plays a noticeable part in the differences between their communication related to the societal level they invoke. This is in parallel with previous research (Bayrak 2020). Yet, it also implies that even though there is a pressure in the field to communicate in a similar, legitimating organisational genre, the institutions also have to comply with the different cultural environments they are operating in and with the ones they are trying to reach through their English online communication.

Conclusion

In this paper, we aimed to show how business schools discursively (re)create their organisational legitimacy in relation to the expression ‘future’.

The corpus-based discourse analysis of the highly ranked 100 business schools revealed a very positive language use related to the future. Furthermore, we were able to identify six main ways these organisations relate to the future: preparing, shaping, adapting, exploring, personal future, (social) responsibility. Through the strategic language-use concerning these agency frames, business schools can also position themselves as important and relevant organisations who can contribute to individual and social futures. Moreover, by doing so they can also react to social criticism regarding their role of the maintaining present form of managerial capitalism.

Notes

The London School of Economics and Political Science was excluded from the collection due to this very reason. Since it is an economics focused institution, their website mostly concentrates on economic education, as well as several of their departments’ sites. Instead of downloading excessive amounts of text from the various departments’ webpages, and thus creating an uneven amount of content on the university’s behalf, we chose to exclude the institution to avoid this inconsistency.

It can go hand in hand with preparing, but it does not have to: in several sentences the school does not imply that they will prepare students for this future, but emphasises for example, that the school is able to adjust to the unavoidable.

‘Lift’ is directly proportional to pointwise mutual information, a basic information-theoretic measure of association (Church & Hanks 1990). A lift value of 1 indicates that the co-occurrence of frames in the LHS and RHS is not higher than expected by chance, values over 1 indicate a higher than chance co-occurrence. Since lift is relative to the basic probabilities of frames or groups of frames, these probabilities are also useful for interpretation. In association rules mining, the probability of frames in both the LHS and the RHS is called support, while the conditional probability of the RHS given the LHS is called confidence.

References

Agrawal, R., & Srikant R. (1994). Fast algorithms for mining association rules in large databases. In VLDB ’94: Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Very Large Data Bases (pp. 487–499). San Francisco: Morgan Kaufmann Publishers Inc.

Baker, P., Gabrielatos, C., Khosravinik, M., Krzyzanowski, M., Mcenery, T., & Wodak, R. (2008). A useful methodological synergy? Combining critical discourse analysis and corpus linguistics to examine discourses of refugees and asylum seekers in the England press. Discourse & Society, 19, 273–306. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926508088962

Barron, G. R. (2017). The Berlin principles on ranking higher education institutions: Limitations, legitimacy, and value conflict. Higher Education, 73(2), 317–333.

Bayrak, T. (2020). A content analysis of top-ranked universities’ mission statements from five global regions. International Journal of Educational Development, 72, 102130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2019.102130

Beusch, P. (2014). Towards sustainable capitalism in the development of higher education business school curricula and management. International Journal of Educational Management, 28(5), 523–545. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-12-2012-0132

Blanco, G. L., & Metcalfe, A. S. (2020). Visualizing quality: University online identities as organizational performativity in higher education. The Review of Higher Education, 43, 781–809. https://doi.org/10.1353/rhe.2020.0007

Bondi, M. (2016). The future in reports: Prediction, commitment and legitimization in corporate social responsibility (CSR). Pragmatics and Society, 7(1), 57–81. https://doi.org/10.1075/ps.7.1.03bon

Bougnol, M. L., & Dulá, J. H. (2015). Technical pitfalls in university rankings. Higher Education, 69(5), 859–866.

Bowman, N. A., & Bastedo, M. N. (2011). Anchoring effects in world university rankings: Exploring biases in reputation scores. Higher Education, 61(4), 431–444.

Bronn, P. S., & Vidaver-Cohen, D. (2009). Corporate motives for social initiative: Legitimacy, sustainability or the bottom line? Journal of Business Ethics, 87, 91–109. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-008-9795-z

Church, K., & Hanks, P. (1990). Word association norms, mutual information, and lexicography. Computational Linguistics, 16, 22–29.

de Saint-Georges, I. (2012). Anticipatory discourse. In C. A. Chapelle (Ed.), The Encyclopedia of applied linguistics (pp. 118–124). Wiley-Blackwell.

Deephouse, D. L., Bundy, J., Tost, L. P., & Suchman, M. C. (2017). Organizational legitimacy: Six key questions. In R. Greenwood, C. Oliver, T. B. Lawrence, & R. E.Meyer (Eds.), The Sage handbook of organizational institutionalism (pp. 27–54). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

van Dijk, T. A. (2007). The Study of Discourse – An Introduction. In T. A. van Dijk (Ed.) Discourse Studies (Vol. 1, pp. xix-xlii). London: Sage Publications.

Efe, I., & Ozer, O. (2015). A corpus-based discourse analysis of the vision and mission statements of universities in Turkey. Higher Education Research & Development, 34, 1110–1122. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2015.1070127

Fairclough, N. (1993). Critical discourse analysis and the marketization of public discourse: The universities. Discourse & Society, 4(2), 133–168. https://doi.org/10.1177/0957926593004002002

Fairclough, N. (2003). Analysing discourse: Textual analysis for social research. Routledge.

Fergnani, A., & Jackson, M. (2019). Extracting scenario archetypes: A quantitative text analysis of documents about the future. Futures & Foresight Science, 1, e17. https://doi.org/10.1002/ffo2.17

Ford, K. S., & Cate, L. (2020). The discursive construction of international students in the USA: Prestige, diversity, and economic gain. Higher Education, 80, 1195–1211. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-020-00537-y

Fuoli, M. (2012). Assessing social responsibility: A quantitative analysis of Appraisal in BP’s and IKEA’s social reports. Discourse & Communication, 6(1), 55–81. https://doi.org/10.1177/1750481311427788

Gee, J. P. (2011). An introduction to discourse analysis: Theory and method. Routledge.

Géring, Z. (2021). Mixed methodological discourse analysis. In J. Burke & A. J. Onwuegbuzie (Eds.), The Routledge Reviewer’s Guide to Mixed Methods Analysis (pp. 161–170). Routledge.

Ghoshal, S. (2005). Bad management theories are destroying good management practices. Academy of Management Learning and Education, 4(1), 75–91. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2005.16132558

Grant, D., Hardy, C., Oswick, C., & Putnam, L. (Eds.). (2004). Sage Handbook of Organizational Discourse. Sage Publications.

Heracleous, L. (2006). Discourse, interpretation, organization. Cambridge University Press.

Huisman, J., & Mampaey, J. (2016). The style it takes: How do UK universities communicate their identity through welcome addresses? Higher Education Research & Development, 35, 502–515. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2015.1107889

Huisman, J., & Mampaey, J. (2018). Use your imagination: What UK universities want you to think of them. Oxford Review of Education, 44, 425–440. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2017.1421154

Király, G., & Géring, Z. (2019). Introduction to ‘futures of higher education’ special issue. Futures, 111(3), 123–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2019.03.004

Király, G., & Géring, Z. (2021). Having nothing but questions? The social discourse on higher education institutions’ legitimation crisis. Journal of Futures Studies, 25(4), 57–70. https://doi.org/10.6531/JFS.202106_25(4).0005

Kosmützky, A., & Krücken, G. (2015). Sameness and difference: Analyzing institutional and organizational specificities of universities through mission statements. International Studies of Management & Organization, 45, 137–149. https://doi.org/10.1080/00208825.2015.1006013

Krücken, G., & Meier, F. (2006). Turning the university into an organizational actor. In G. S. Drori, J. W. Meyer, & H. Hwang (Eds.), Globalization and organization: World Society and organizational change (pp. 241–257). Oxford University Press.

Miotto, G., Blanco-González, A., & Díez-Martín, F. (2020). Top business schools legitimacy quest through the Sustainable Development Goals. Heliyon, 6(11). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e05395

Morphew, C. C., & Hartley, M. (2006). Mission statements: A thematic analysis of rhetoric across institutional type. The Journal of Higher Education, 77, 456–471. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2006.11778934

Murcia, M. J., Rocha, H. O., & Birkinshaw, J. (2018). Business schools at the crossroads? A trip back from Sparta to Athens. Journal of Business Ethics, 150(2), 579–591. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3129-3

Oddo, J. (2013). Precontextualization and the rhetoric of futurity: Foretelling Colin Powell’s UN address on NBC News. Discourse & Communication, 7(1), 25–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/1750481312466480

Özdem, G. (2011). An analysis of the mission and vision statements on the strategic plans of higher education institutions. Educational Sciences: Theory and Practice, 11, 1887–1894.

Palmer, T. B., & Short, J. C. (2008). Mission statements in US colleges of business: An empirical examination of their content with linkages to configurations and performance. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 7, 454–470. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2008.35882187

Parker, M. (2018). Shut down the business school. What’s wrong with management education. Pluto Press.

Phillips, N., & Malhotra, N. (2008). Taking social construction seriously: Extending the discursive approach in institutional theory. In R. Greenwood, C. Oliver, K. Sahlin, & R. Suddaby (Eds.), The Sage handbook of organizational institutionalism (pp. 702–720). Sage.

Phillips, N., Lawrence, Th. B., & Hardy, C. (2004). Discourse and institutions. Academy of Management Review, 29, 635–652. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2004.14497617

Sauntson, H., & Morrish, L. (2011). Vision, values and international excellence: The ‘products’ that university mission statements sell to students. In M. Molesworth, R. Scullion, & E. Nixon (Eds.), The marketisation of higher education and the student as consumer (pp. 73–85). Routledge.

Scott, W. R. (2003). Organization. Rational, Natural and Open Systems. New Jersey: Pearson Education International.

Suchman, M. C. (1995). Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. The Academy of Management Review, 20, 571–610. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.1995.9508080331

Suddaby, R., & Greenwood, R. (2005). Rhetorical strategies of legitimacy. Administrative Science Quarterly, 50(1), 35–67. https://doi.org/10.2189/asqu.2005.50.1.35

Suddaby, R., Bitektine, A., & Haack, P. (2017). Legitimacy. Academy of Management Annals, 11(1), 451–478. https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2015.0101

Tonkiss, F. (2012). Discourse analysis. In C. Seale (Ed.), Researching Society and Culture (pp. 405–423). Sage.

Vaara, E., & Tienari, J. (2008). A discursive perspective on legitimation strategies in multinational corporations. Academy of Management Review, 33(4), 985–993. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2008.34422019

van Leeuwen, T. (2008). Discourse and practice. New tool for critical discourse analysis. Oxford University Press.

Yu, D., & Bondi, M. (2019). A genre-based analysis of forward-looking statements in corporate social responsibility reports. Written Communication, 36(3), 379–409. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741088319841612

Acknowledgements

This paper was prepared as part of the project ‘The future of business education’ funded by National Research, Development and Innovation Office, Hungary (FK127972).

Funding

Open access funding provided by Budapest Business School - University of Applied Science.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Highlights

• Business schools’ discursive legitimacy claims are future related.

• A progressive vision dominates the representation of future in business schools’ communication.

• Business schools apply six future-related agency frames in their communication.

• Business schools use social role-related and action-related discursive strategies of legitimacy.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Géring, Z., Tamássy, R., Király, G. et al. The portrayal of the future as legitimacy construction: discursive strategies in highly ranked business schools’ external communication. High Educ 85, 775–793 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-022-00865-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-022-00865-1