The story of how Sugata Mitra put a computer in a hole in a Delhi wall at the end of the last century and how uneducated children used it to teach themselves all manner of things is now well known. So is the story of how Mitra’s work inspired the novel, Q&A, that became the film Slumdog Millionaire. But no government has taken more than a passing interest in his vision. Nor, although teachers have often tried his methods and reported miraculous results, have professional associations and university education departments responded with much enthusiasm. Seventeen years after Mitra conceived the idea that a computer could act as a kind of village well from which children could freely draw knowledge, the educational world treats him with deep scepticism.

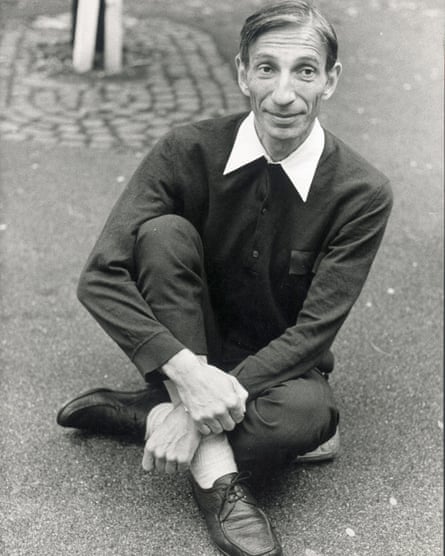

So when I meet him over lunch at Newcastle University, where he is professor of educational technology, I intend to ask how he plans to get his ideas more widely adopted and what answers he has to critics who accuse him of “magical thinking”.

But Mitra launches into a speech about “what is happening to the world”. He says: “A generation of children has grown up with continuous connectivity to the internet. A few years ago, nobody had a piece of plastic to which they could ask questions and have it answer back. The Greeks spoke of the oracle of Delphi. We’ve created it. People don’t talk to a machine. They talk to a huge collective of people, a kind of hive. Our generation [Mitra is 64] doesn’t see that. We just see a lot of interlinked web pages.

“In India, I found two illiterate people texting each other. They had invented a language for themselves which you and I would not understand. I wonder: are there such things as illiterates at all? Yes, if we give them an examination on grammar, but maybe we’ve got the definition wrong and there’s a new literacy that we’re unaware of.

“You can ask nine-year-olds to find out about the entanglement of particles and they will come back to you and explain in their nine-year-old way – not as a graduate would of course – exactly what it is. Things can be in two places at the same time, they say.”

Mitra says all this with fluency, conviction and wit, laced with just enough self-deprecation and speculative doubt to win you over. He’s a star turn at conferences, even if audiences frequently shout “rubbish” at him. “I hate to say it, but I think they invite me for entertainment,” he says.

And what entertainment! He brushes aside all established thinking about education. Examinations as we know them will have to go, he says. In India, the army is needed to stop students taking their smartphones into exams. Before long, the soldiers will need to ban wristwatches and eye-glasses.

“Within five years, you will not be able to tell if somebody is consulting the internet or not. The internet will be inside our heads anywhere and at any time. What then will be the value of knowing things? We shall have acquired a new sense. Knowing will have become collective.”

The status of reading, writing and arithmetic as fundamental skills – that, too, must be questioned, Mitra argues. Though “not usually a particularly aggressive fellow”, he has become aggressive about this, he says. “I can find on my phone a piece of Japanese and the phone will read it to me in English. So can I read Japanese? No. But if you imagine me and my phone as a single entity, yes. Very soon, asking somebody to read without their phone will be like telling them to read without their glasses.”

Even Jean Piaget’s supposedly immutable stages of child development – familiar to every trained teacher – now need a rethink, according to Mitra. His iconoclastic approach is, I think, at least partly attributable to his having no experience of school teaching and no academic background in education. His visionary ideas are reminiscent of the de-schooling movement of the early 1970s. That, too, argued that the conventional baggage of education, such as teaching knowledge in classrooms, was outdated. That, too, was led by a man with no professional background in education: Ivan Illich, an Austrian Catholic priest and philosopher. It faded away within a decade.

Mitra was born to an affluent, middle-class family in Calcutta who later moved to Ahmedabad and then to Delhi, where Mitra, an only child, went to Jesuit schools. After a physics degree in Calcutta and a PhD in Delhi, he could get a job only as a computer programmer for NIIT, an India-based multinational that sells IT training packages. He was soon moved to teaching other people how to program. “I ended up,” he says, “doing what I most hated: standing in front of a class.” At NIIT, he began his hole-in-the-wall experiment.

It was repeated in several hundred learning stations in India and elsewhere. But none of the original holes is still operating. Mitra has developed what he calls the “self-organised learning environment” (Sole), also known as “the school in the cloud”, which transfers the hole to the inside of a building, usually a school. Twenty children are asked a “big question” such as “Why do we learn history?”, “Is the universe infinite?”, “Should children ever go to prison?” or “How do bees make honey?” They are then left to find the answers using five computers. The ratio of four children to one computer is deliberate: Mitra insists that the children must collaborate. “There should be chaos, noise, discussion and running about,” he says.

The teacher’s role is to encourage, prompt and then to lead a session where the children report back. In developing countries, with teachers in short supply, that role can be performed by someone else, including a British grandmother with a Skype connection. Though many of those involved are young locals, this became known as the “granny cloud”.

Mitra persuaded about 40 schools in the north-east of England to try out Soles, starting with a Gateshead primary. News of this experiment, Mitra says, “went viral”. Even he doesn’t know how many schools across the world are operating Soles. He does know that hundreds of teachers report back enthusiastically. “They say: we don’t have time to wait for academic findings, we know it works.”

But the lack of academic findings is precisely what troubles Mitra’s critics. They say his claims need to be tested by properly controlled experiments that allow for the galvanising effects temporarily created by any new idea, which will lead to papers published in reputable, peer-reviewed academic journals.

The most quoted paper, written jointly by Mitra with a teacher at the Gateshead primary, was published in a little known journal with a low impact rating. It reported startling results. Year 4 children (aged eight to nine) were given questions from GCSE physics and biology papers. After using their Sole computers for 45 minutes, their average test scores on three sets of questions were 25%, 26% and 13%. Three months later – the school having taught nothing on these subjects in the interim – they were tested again, individually and without warning. The scores rose to 57%, 80% and 16% respectively, suggesting the children continued researching the questions in their own time. For questions on molecular structure, radiation and geography, taken from A-level papers by another year 4 group, results were more mixed but still remarkable.

The authors admit the samples were tiny and, to draw valid conclusions, more rigorous measurements are needed.

Some critics go further, arguing that testing children on thin slices of a GCSE or A-level syllabus tells us nothing. Knowledge is incremental and requires competent scaffolding if it is to lodge properly in children’s minds, they say.

Using money from a $1m prize he won in 2013 for a celebrated TED lecture, Mitra has set up seven Soles, five in India, two in deprived areas of north-east England, which he is evaluating with a team from Newcastle University. I suggest he needs fully independent evaluation, including a means of measuring long-term results after the novelty effects wear off. He quotes a few anecdotal examples of eight-year-olds who started at a hole-in-the-wall and later made good, including a boy who did a PhD in evolutionary biology at Yale. “Most of the others probably became rickshaw drivers, but the one doing evolutionary biology is surely worth it.”

Pressed further, he says the main benefit of his methods is that children’s self-confidence increases so that they challenge adult perceptions. “But most people don’t see that as an educational objective. As far as they are concerned, the children just become more unruly.”

The proposition that Soles can provide intellectual stimulus and encourage children to achieve more than we previously thought possible is entirely reasonable. So are the propositions that children can benefit from collaborative learning and that banning internet use from exams will get trickier, to the point where it may prove futile. It’s worth remembering that new technologies nearly always deliver less than we expect at first and far more than we expect later on, often in unexpected ways.

But Mitra seems to argue – it can be hard to tell whether he’s exaggerating for dramatic effect – that we should transform the whole basis of schooling. And to convince us of that, I fear, he needs far better evidence than he has or seems likely to get.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion