For a long time I hated tuition fees. I hated them for moral reasons and for selfish ones. I obviously wasn’t too thrilled to pay them. If I’m honest, it felt like a tax on effort, on intelligence, on wanting to make a contribution to society. ‘The country will benefit from me and people like me,’ I smugly and conveniently believed, ‘and so my education should be a taxpayer investment.’

A better reason to hate them was, I believed, the deterrent effect that they would have on poorer people entering university. If you make it more expensive to get a degree then naturally that’s going to favour people with more money. That much seems pretty obvious. It’s certainly obvious to Jeremy Corbyn, who has a whole policy built around the idea: scrap tuition fees completely, and fund the £10bn required by raising national insurance or corporation tax or borrowing money from unicorns or something.

Solid stuff. There’s just one teeny tiny problem. The evidence shows that if you want to invest ten billion reducing inequality, the university system is about the worst place you can possibly put it. In fact it’s such a bad idea that it could have the exact opposite effect.

There are two basic problems with my old beliefs. The first is the impact high tuition fees have actually had, which we have solid data on for several years now. The second is a misconception about where inequality takes root in Britain’s schools.

Let’s look at some numbers. In 2015, UCAS report that “18 year olds from across the UK were more likely to apply to higher education than in any previous year.”

That’s for all students though, so what about the poorer ones? “In 2015, application rates of 18 year olds living in disadvantaged areas in all countries of the UK increased to the highest levels recorded.” This is as a percentage of the population, not an absolute number, so we’re talking about a genuine increase here even above the rate of population increase generally.

Even more striking is how those figures have changed over a decade. In England, 18 year olds living in disadvantaged areas were a staggering 72% more likely to apply for higher education in 2015 than in 2006. In Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland the figures were 63%, 39% and 36% - lower, but still a huge increase.

Maybe the increase among rich kids is even greater though? Nope. Inequality is actually falling. “In 2006 advantaged UK 18 year olds were 3.7 times more likely to apply that disadvantaged 18 years olds.” By 2014 the ratio had fallen to 2.4. “A similar fall is seen for each country of the UK.”

The data simply couldn’t be clearer. In the last decade, in spite of rising tuition fees, students are more likely to apply for university, poorer students are more likely to apply for university, and the inequality gap – while still a problem – has closed. We’re not talking about small debatable improvements here – these are massive changes.

At best, there is no evidence here that the £10bn Jeremy Corbyn proposes to scrap fees and reintroduce grants would make any difference in tackling inequality. At worst, it could reverse the improvements we’ve seen.

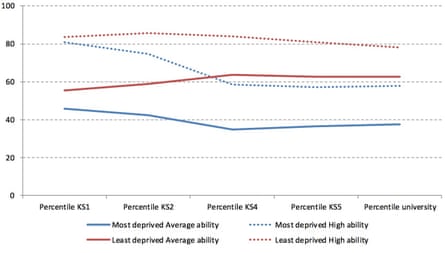

Which brings me on to that second problem. The truth is that the rot of inequality sets in years before a pupil reaches the age to be thinking about university. Research published in 2014 by the Centre for Analysis of Youth Transitions – and a stack of similar studies before that – tell us exactly where. The answer lies in the following chart.

The chart above tells the story of four groups of children. The red lines show the richest 20% while blue lines show the poorest 20%. The dotted lines are the high ability kids from each demographic, and the solid lines are the average ability children.

The high ability kids start off about the same, but over time the rot sets in. The gap grows and grows, with a dramatic decline for the less advantaged kids between key stage 2 (7-11) and key stage 4 (14-16). The same gap opens up between the average ability kids too, to such a large extent that by the time the four groups of children reach their GCSEs, the average ability rich kids are pulling ahead of the high ability poor kids, who by the age of 16 are already stuck in a long term rut that will affect how the rest of their lives unfold.

So taking all of the above into account, the impact of tuition fees to date and the evidence about where inequality sets in among children, I think I’m pretty clear now on where I’d like to see extra cash spent.

It’s not fashionable. You won’t see many middle class students protesting about it, and it tends to be overlooked by graduate writers (like me) who tend to assume that the world revolves around our experiences; but if you want to spend ten billion quid addressing inequality in the education system then the target is pretty obvious – don’t give tax breaks to us graduates, pour the cash into secondary schools instead.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion