One of the most common challenges for student journalists is identifying the right human sources to turn a lead into a fleshed out story. And one of the most common mistakes is not to spend enough time on this vital step in the reporting process.

To help with this, here’s a framework for brainstorming potential sources.

The five categories of source

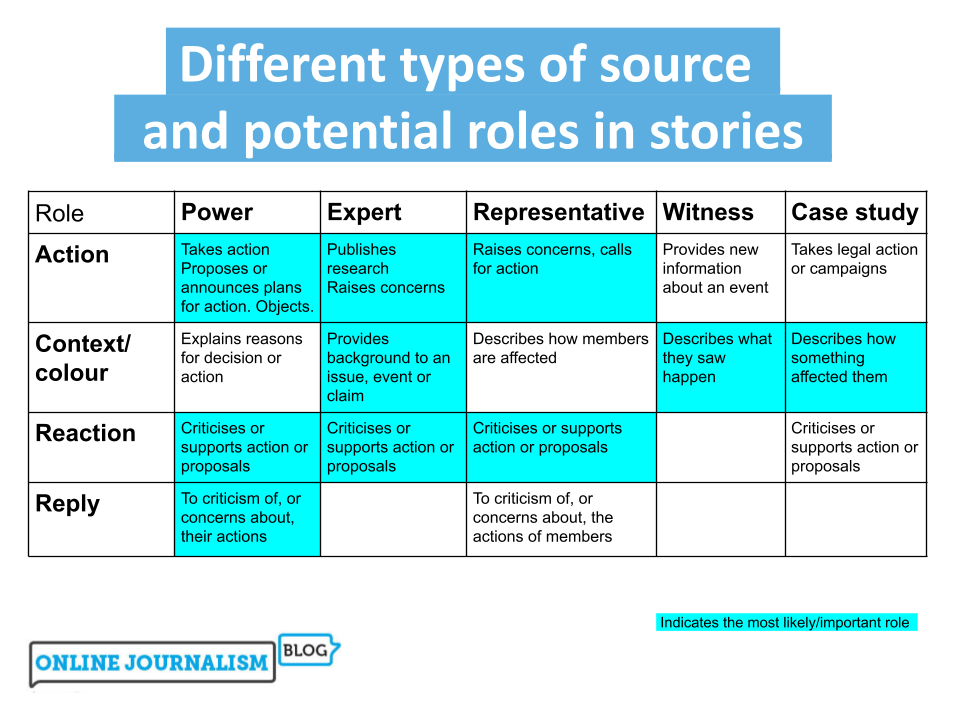

There are five categories of source in the framework:

- Power (political, financial or cultural): those who are responsible for preventing or stimulating the events you’re reporting on — or who have the power to change it (or both)

- Expertise (academic, professional, experiential): those who can provide the big picture, context, or analysis

- Representative: those who can act as the voice of a particular group involved in the story

- Witness: who can describe first hand an event that occurred

- Case study who can help the audience understand the impact of the issue we are reporting on

In the case of a story about crime, for example, powerful sources would include the relevant police force or team (e.g. the fraud squad), the part of government responsible for policing, and the politicians who manage that. But also relevant here would be opposition politicians who have the power to change policy, if elected.

Expert sources would include academics who have researched this type of event, but also professionals who have worked on similar cases in the past.

Case studies are likely to be people who have been affected by similar events in the past: for example, victims of crime and their families. Representatives are likely to be charities who campaign on their behalf, such as charities for victims of crime — or a local MP elected by their constituents to play just that role.

Four ‘roles’ in the story

Having identified the five categories of source, it is useful to consider the roles that they tend to play in a story.

Often we are looking for sources because we have identified a ‘story lead’ involving something that has happened or happening — but that alone isn’t enough to make a strong (that is, clear, accurate and engaging) story. We need context and colour, reaction, ideally some sort of response — and potentially action.

- Context and colour provide further details about the newsworthy event: for example witnesses might describe what happened; case studies might explain how an issue affects them; experts might explain the background to the issue in question, or whether it is getting better or worse.

- Reaction helps move a story on from the initial event, through confirmation, criticism, expressions of support, or questions — typically raised by representative groups. In some cases a reaction can become an action…

- Action, like reaction, can also move a story on: it might be someone telling you they have now taken action, or that they plan to, or it might be action in the form of ‘raising concerns’ or ‘calling for something to be done’.

- Reply is different to reaction — it is often a reply to the concerns or questions raised. Where a person or organisation or group is criticised (explicitly or implicitly) then a right of reply will need to be sought from whoever is responsible for a problem or event.

You can also see that particular types of source tend to be needed more often to play particular roles: context is most often provided by experts, and reaction by representatives; a response is most often sought from those in power. Witnesses are almost entirely quoted on details of description. Case studies provide the emotional context that helps us understand the individual impact of current issues.

Where are your blind spots?

Mapping out a framework in this way can help identify blind spots in our sourcing, and generate ideas for sources we might start to look at. Simple questions to ask might include:

- Does my story have a reaction to what’s happened? If not, identify who is affected and which organisations (unions, charities, membership groups) might represent them

- Does my story have context? If not, spend time identifying experts in the field and approaching them for quotes

- Does my story have a ‘reply’ in it? If not put aside time to identify which people might have some power in this issue

- Are there likely to be witnesses to the story event? If so, where and how might you find them?

- Does my story answer the question “Why does this matter?” If not, see if you can find a person whose experiences act as a case study (charities often know people who are willing to speak about their experiences)

- Does my story answer the question “What is being done?” If not, identify people in a position to do something, and ask them.

Adjusting the story angle to new information

Filling a blind spot can not only improve your reporting — it can also give you a stronger new angle to the story.

If an organisation says it has decided to take some sort of action as a result of the information you’ve drawn their attention to, then that often becomes the lead (what was the new information then becomes the context to that).

If a group reacts to your questions by criticising or supporting something, that might become the story (this ‘follow-up’ is a common way of finding a new angle on an existing story).

A strong quote from a case study might become the headline to the resulting story, and them ‘speaking out’ or ‘revealing’ their experience becomes the main angle.

If, when given a right of reply, an authority issues a denial, or acknowledges that mistakes were made, this can become a stronger ‘top line’ for the story.

Here are some examples of each:

- Reaction: Anger as Roma teen shot by Greek police dies

- Reply: EU corruption scandal: MEP denies Qatar bribery after over €1m seized

- Action: Give MPs deadline on hiring relatives, campaigners urge

- Context: Tony Hudgell: Family appalled at Gatwick wheelchair wait

If you struggle to find one particular type of source then you know that’s an area you need to work on. Devote some time to expanding your contacts book between stories, and reading up on newsgathering techniques for finding experts or case studies, witnesses or representatives — or the people that ultimately need to be held to account.

Pingback: Tendencias en periodismo en 2023 - Medianalisis