Mirjam Neelen & Paul A. Kirschner

We’re approaching 2023 and we wish we didn’t have to write this blog. It’s not as ‘stylish’ as the title might suggest. Unfortunately, the idea that we should adapt instructional/learning methods for various ‘learning styles’ because it accommodates for diversity is still flourishing. It’s worth exploring why that idea is fundamentally flawed and what we should do instead.

Recently, a very senior learning leader[1] posted on LinkedIn about the importance of acknowledging workplace diversity and (s)he then used learning styles as an example of how we can accommodate for diverse needs in the context of learning. (S)he used this article, in which Terrence Maltbia, associate professor of organisation and leadership at Columbia University, argues that employers should understand individual differences and ‘personalise learning accordingly’. He goes on to explain Kolb’s learning styles (note that Kolb isn’t referenced in the article): diverging, assimilating, converging, and accommodating. He then claims that ‘learning designers should know that learning styles exist’ and that, when people identify their own learning style, it allows us to produce ‘greater organisational empathy’ and that that ‘invites learners to flourish’. This might sound nice and many probably welcome empathetic organisations and flourishing learners.

Next, he throws in visual and auditory learners, referring to the VARK learning styles model, which are, again, not referenced.

Despite the fact that Maltbia says to be aware of ‘the core critique’ on learning styles, he still argues that organisations need to affirm people in their learning styles, and adjust and adapt work and learning to those styles.

There are two major problems with both the article and the learning leader’s post.

- The idea that accommodating for learning styles is ‘good’ because it accommodates for diversity, which in turn helps organisations to do better when it comes to inclusion and equity is fundamentally flawed.

- Senior leaders who post with good intention yet use a fundamentally flawed approach is highly problematic because they should be advocates for improving (evidence-informed!) learning and development practice, instead of focusing on the superficial message and the ‘empathetic’ tone without realising how flawed the resource is that they use to reinforce their message.

Let’s start with untangling the first problem.

The learning leader’s post implies a linkage between learning styles and diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI). The article (s)he references suggests that, if we don’t acknowledge that learning styles exist and accommodate for them when designing for work and learning, we’re not acknowledging diversity and we’re not being inclusive. It proposes that accommodating for learning styles means that we put ‘people at the centre’ and that tailoring approaches and methods to people’s preferences is a good thing.

DEI is always tricky. Most people want to do ‘the right thing’ (and rightly so!), yet it’s not so easy to ‘get DEI right’. It’s a very complicated topic that needs to be approached with caution and precision. When looking at the debate that followed on the senior learning leader’s post on LinkedIn, the proponents of the ‘learning styles’ message are loud and clear towards those who criticise Maltbia’s assumptions: “Oh, don’t be such a pain! It doesn’t matter what we call it – learning styles or learning preferences – it’s about accommodating for people’s needs and preferences and that’s an intention we should embrace!”

The thing is: it does matter. Good intentions aren’t enough. The expression ‘the road to hell is paved with good intentions’ exists for a reason. Not only are good intentions not enough, they can also be harmful, such as in this particular case!

DEI is not about ‘having good intentions and accommodating for people’s preferences’, it’s about (what follows is an incredibly simplistic summary of what DEI is about) considering what makes individual people ‘unique’, for example based on their backgrounds, personalities, life experiences, beliefs, basically anything that makes us ‘who we are’. It’s about recognising, respecting, and valuing differences (e.g., based on ethnicity, gender, age, disability, sexual orientation, educational background, income level, life experience, or whatever).

Inclusion is about making sure that people feel, and are, valued and respected. And then lastly, equality is about people’s ability to participate equally in ‘life’; in the workplace, in education, in accessing goods and services.

The idea that accommodating for learning styles is ‘good’ because it accommodates for diversity so that we’re doing better when it comes to inclusion and equity is fundamentally flawed. Here’s why.

The whole idea of ‘learning styles’ is based on the fact that we’re all different (we are) and that we all learn in different ways (we don’t when it comes to our cognitive architecture as that’s essentially the same for everyone[2]). However, as always, the devil is in the details. What does it mean when we say that we ‘all learn in different ways’? Spoiler alert: It’s not about learning styles.

Learning styles: Intentions & evidence

Let’s make something clear. The research on learning styles is about people’s learning preferences. It all started in the 1970s. In 1971, Kolb published ‘Individual learning styles and the learning process’. In 1975, Dunn and Dunn published their article ‘Learning Styles, Teaching Styles’. In short, the idea is that, if we figure out what people’s individual learning preferences are, we can then accommodate for them, so that… they can then learn better.

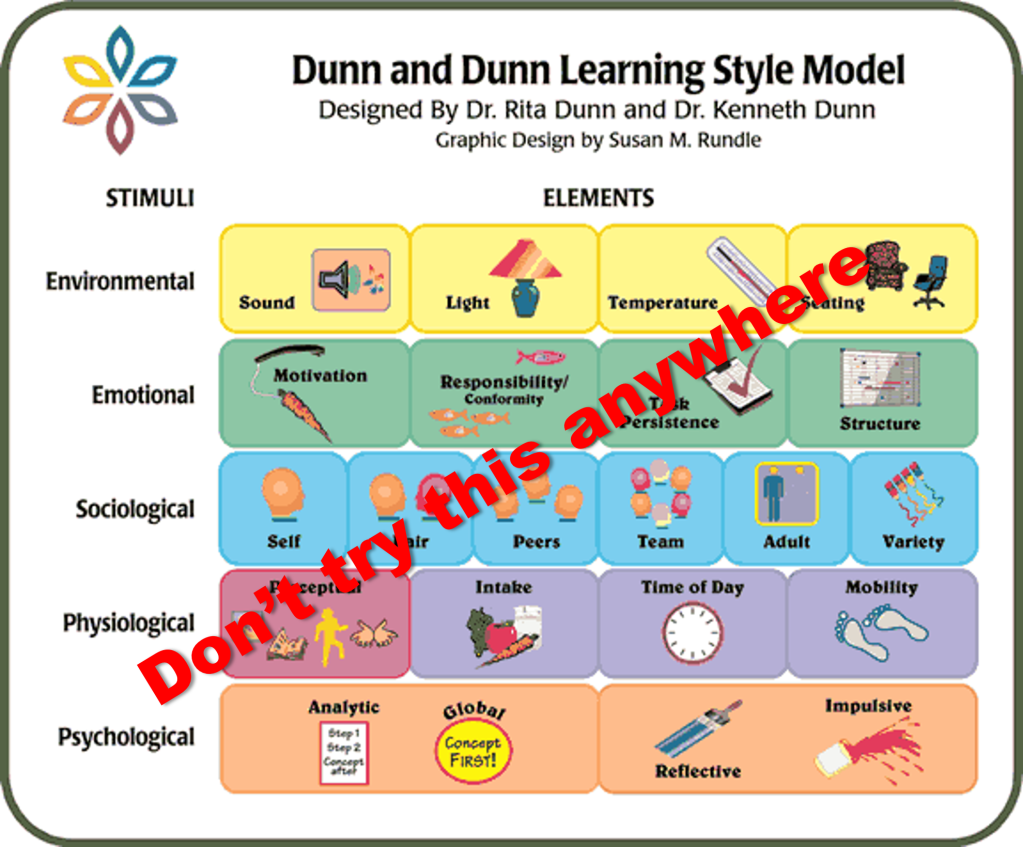

The image shows an example of what such a ‘learning styles inventory’ (in this case, a Dunn & Dunn’s version) can look like.

There’s a big underlying assumption here that when we help people to follow their preferences, that that’s a good thing. Of course, this isn’t necessarily the case. People have food preferences, too! Salty, sweet, fatty or a combination of two or all three (we love sea-salt caramel ice cream)! Should people follow their preferences? Of course not, that wouldn’t be healthy! In fact, when it comes to learning, there’s a great difference between what people prefer and/or believe they need to learn best versus reality. Yes, people have preferences. However, following these preferences doesn’t necessarily lead to better learning.

We know this, because it has been studied. Multiple times. In order to determine if accommodating instructional/learning methods to preferred learning styles is actually helping people to learn better, we need evidence that, for example, type A learners learn better with method A, whereas type B learners learn better with method B (also note that often, learning styles are identified through self-assessment questionnaires, so they’re usually perceived learning styles or in actuality preferences). Also, if we really want evidence that tailoring to learning styles helps people to learn better, our evidence should also show that type A learners don’t learn with method B and that type B learners don’t learn with method A (Neelen & Kirschner, 2020). This is known as the meshing hypothesis. If you’re looking for more detail, read ‘Do learners really know best?’ (Kirschner & van Merriënboer, 2013). After all, if the latter isn’t the case, why would we invest in adapting our learning solutions to learning styles? We’d be wasting money. Only if learner type A learns better with method A and worse with type B, it’s worth the investment.

To sum it all up, there are multiple studies that have demonstrated that methods that are designed to accommodate for particular learning styles are uncorrelated or negatively correlated with learning outcomes (e.g., Clark, 1982, Van Merriënboer, 1990), or, more recently, Pashler et al., (2008) who conducted a meta-analysis on the ‘learning styles’ literature and concluded that “the contrast between the enormous popularity of the learning-styles approach within education and the lack of credible evidence for its utility is, in our opinion, striking and disturbing” (p 117).

Key message: There’s no evidence that accommodating learning methods for people’s learning styles leads to better learning. Therefore, we shouldn’t waste money on designing different pathways based on learning styles. We should also keep in mind that designing different pathways based on learning styles can actually be harmful for learning.

What we should focus on instead: We should ask what the best learning methods are for a) what needs to be learned (learning how to play tennis requires a very different method than learning how to manage a team of experts), b) where the learners are in the learning process (e.g., how much prior knowledge do they have; experts in an area need a different type of instruction than novices for example), and c) specific learner needs, such as – and there can be a lot here! – accessibility, language, devices, etc.

Although we think that the above is enough evidence to accept that focusing on ‘learning styles’ means we’re betting on the wrong horse and that instead, we should look at the evidence that actually helps us to design effective learning interventions (e.g., evidence on how our cognitive architecture works, how we process information, what we need to remember things, what we need to learn how to do things better or differently), there are two other problems with learning styles that we’d like to point out.

First, Coffield et al., (2004) describe 71 different learning styles models, based on various existing learning styles models as described in the literature. How would we tailor our designs to all these options? It’s simply impossible. Even when we just look at the Dunn & Dunn inventory above, we need to ask ourselves: What would accommodating for all these preferences mean in practice?

Second, all these models somehow assume that we can classify people in distinct groups[3]. This assumption not only doesn’t have much support from objective studies (e.g., Druckman & Porter, 1991), we also wonder, especially given the fact that DEI is brought into the debate by those who advocate for tailoring methods based on learning styles: How inclusive is it to try to pigeonhole people into a learning style? Of course, most people don’t fit one particular style (not even when we only look at preferences! An individual might prefer something else based on the task at hand, the amount of sleep they had, their interest in the task, and so forth). Finally, try teaching how a Bach sonata sounds via pictures to a visual learner or how a Dali painting looks to a kinaesthetic learner or the different shades of red to an auditive learner. Sounds stupid right? Yes, and that’s because it is!

Key message: The literature describes 71 different learning styles. Deciding which ones we’d accommodate for is a bit like playing roulette and trying to pigeonhole people into certain learning styles, and isn’t taking diversity and all kinds of circumstances into account.

What we should focus on instead: We should ask what the best learning methods are for a) what needs to be learned (learning how to play tennis requires a very different method than learning how to manage a team of experts), b) where the learners are in the learning process (e.g., how much prior knowledge do they have; experts in an area need a different kind of instruction than novices for example), and c) specific learner needs, such as – and there can be a lot here! – accessibility, language, devices, etc.

Last, but not least, we’d like to ask all senior learning people to be very cautious and diligent with what they share on social media, no matter how well intended the message is. We can’t expect all senior leaders to be aware of all of the evidence from the learning sciences per se, but we can expect them be aware that they aren’t aware and therefore, be super cautious. After all, they have a responsibility to support the learning professionals in their organisations to improve their practice in order to support the workforce to do their jobs better or differently. Don’t get in the way by spreading myths. That’s just not very stylish.

References

Coffield, F., Moseley, D., … & Ecclestone, K. (2004). Learning styles and pedagogy in post-16 learning: A systematic and critical review. London: Learning and Skills Research Centre.

Clark, R. E. (1982). Antagonism between achievement and enjoyment in ATI studies. Educational Psychologist, 17(2), 92-101.

De Bruyckere, P., Kirschner, P. A., & Hulshof, C. D. (2015). Urban myths about learning and education. Academic Press.

Dunn, R., & Dunn, K. (1975). Learning styles, teaching styles. NASSP Bulletin, 59(393), 37-49.

Kolb, D. A. (1971). Individual learning styles and the learning process. MIT.

Neelen, M., & Kirschner, P. A. (2020). Evidence-informed learning design: Creating training to improve performance. London: Kogan Page Publishers.

Pashler, H., McDaniel, M., Rohrer, D., & Bjork, R. (2008). Learning styles: Concepts and evidence. Psychological science in the public interest, 9(3), 105-119.

van Merriënboer, J. J. (1990). Instructional strategies for teaching computer programming: Interactions with the cognitive style reflection-impulsivity. Journal of Research on Computing in Education, 23(1), 45-53.

[1] We’re not referencing the post here, because this is not about criticising an individual. It’s about calling out what we think is the responsibility of a senior leader in learning.

[2] Yes, some are slower or faster than others, some need more explanations or analogies than others, but our sensory memory, working memory, and long-term memory plus the principles guiding their functioning are essentially the same for all of us.

[3] This is also one of the major problems with the Myers-Briggs Inventory. See, for example, https://areomagazine.com/2021/03/09/should-you-trust-the-myers-briggs-personality-test/

Whew! That was detailed.

My speculation about the interest in LS is that it’s intuitively attractive, easy to understand and intellectually easy(lazy).

Jim

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Nonpartisan Education Group.

LikeLike

‘Leader’ (sic) in question…

https://www.hrdive.com/news/learning-styles-at-work/624582/

LikeLike

Reblogged this on From experience to meaning….

LikeLike

Reblogged this on kadir kozan.

LikeLike