This article reflects on current practices and directions for digital transformation through a framework that supports the strategic responses and structural changes that higher education institutions could implement to enhance digital teaching and learning.

Higher education is in the era of digital transformation (Dx). Learning technologies and digital platforms are no longer an afterthought; they are critical for teaching and learning. The COVID-19 pandemic served as a catalyst for Dx, forcing colleges, universities, instructors, and students to shift online rapidly. Some instructors and students were prepared for the shift; those who were unprepared had to catch up quickly.Footnote1 This article reflects on current practices and directions for Dx through a framework that supports the strategic responses and structural changes that higher education institutions could implement to enhance digital teaching and learning.

Defining Digital Transformation

As experts in learning design, instruction, and educational technology, we define Dx for digital learning in the higher education context as leveraging digital technologies to enable major educational improvements, enhance learner and instructor experiences, and create new instructional models through policies, planning, partnerships, and support. Our definition builds on existing research and Gregory Vial's 2019 definition of Dx. It also aligns with the EDUCAUSE definition of Dx: "a series of deep and coordinated culture, workforce, and technology shifts that enable new educational and operating models and transform an institution's operations, strategic directions, and value proposition."Footnote2

Dx is driven by and built on digital technologies. It changes the educational landscape significantly. Keeping up with Dx helps higher education institutions operate effectively, stay competitive in an increasingly digital world, and prepare learners for the digital workplace.

Building a Dx Framework for Digital Learning in Higher Education

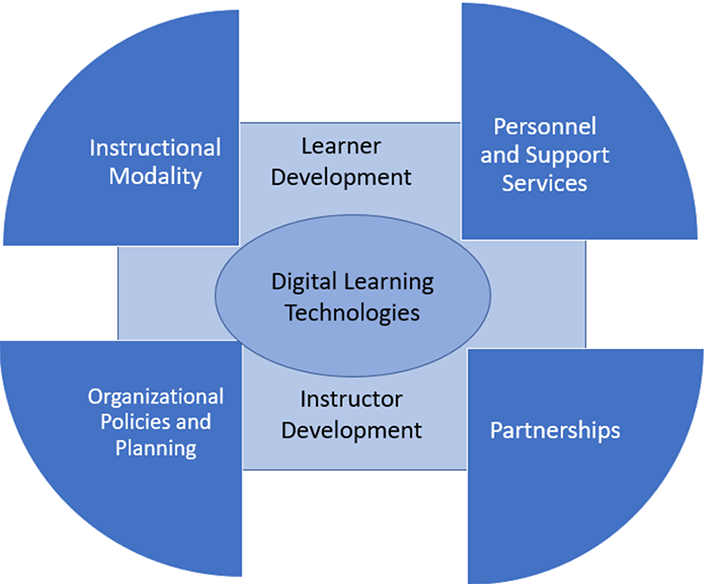

We have witnessed Dx in higher education institutions through our work as university professors and educational technology researchers. In this article, we propose a framework focused on integrating digital technologies to cause Dx in higher education settings. According to Vial, structural changes in four areas are critical for Dx: organizational structure, organizational culture, leadership, employee roles, and skills.Footnote3 Our Dx framework for digital learning in higher education discusses seven aspects within each of those four areas: digital learning technologies, instructional modality, personnel and support services, organizational policies and planning, instructor development, learner development, and partnerships (see figure 1). Some colleges and universities might already be in the middle of Dx, and others might just be getting started.

- Digital Learning Technologies. Dx is grounded in digital technologies, which play a crucial role in digital teaching and learning.Footnote4 Digital technologies can be used in various instructional modalities to engage learners. Instructors can use these technologies to build engaging digital teaching and learning solutions. However, effective digital teaching and learning in higher education settings require significant increases in infrastructure to support these technologies. Some commonly used digital teaching and learning technologies are described below.

- Learning management systems (LMS). An LMS is used to house all course materials, modules, and activities. The instructor can send announcements, engage in discussions, develop and grade assignments, and maintain an online grade book in the LMS.

- Synchronous technologies. Synchronous technologies are used to conduct real-time online meetings. Synchronous technologies include various functionalities, such as audio and video, text/chat, screen sharing, polls, whiteboards, and breakout rooms for small group discussions. These functionalities can help instructors maintain interactivity in online classrooms.Footnote5

- Multimedia applications. Multimedia can engage learners and includes audio, video, and other interactive elements.Footnote6 Multimedia software can be used to record microlectures, demonstrations, orientations, etc. Some multimedia software is open access. More robust applications must be purchased. Some multimedia applications can also be embedded within the LMS for easy access and use.

- Collaborative applications. Web-based or cloud-based word processing, presentation, social participation, and whiteboard applications allow students to collaborate online with their peers and instructors.

- Cloud-based technologies. Colleges and universities rely on various cloud-based applications. Some faculty use cloud-based applications to store files so they can access them from anywhere in the world and aren't restricted to their office computers.

- Emerging technologies. Artificial intelligence (AI), extended reality (XR), augmented reality (AR), virtual reality (VR), analytics, and other emerging technologies can enable more innovative and engaging teaching methods and learning experiences.Footnote7

This is not an exhaustive list of the technologies that can be used for digital teaching and learning. Technology leaders need to evaluate the outcomes of each technology and consider its quality and cost before purchasing it for their campuses. Technology leaders should also examine their technology infrastructure to ensure it is adequate for digital teaching and learning.Footnote8

- Instructional Modality. Education can be offered through a number of instructional modalities. When a college or university offers several learning modalities or courses in more than one modality, students can enroll in the modality that works best for them. Following is a list of common instructional modalities.

- On-campus technology-enhanced. In this modality, teaching and learning occur in person, and technology is used to enhance instruction.

- Hybrid/blended. This modality blends in-person and online instruction to provide students with the flexibility of on-campus and online learning.

- Asynchronous online. In this modality, teaching and learning occur online without any real-time meetings.

- Synchronous online. In this modality, teaching and learning occur online in real time.

- Bichronous online. This modality blends asynchronous and synchronous online teaching and learning. Students participate in the asynchronous classes at the time and location of their choice, and they participate in the synchronous classes in real time.Footnote9

- HyFlex. This modality offers the most flexibility. It combines in-person and online students in the same classroom.Footnote10 HyFlex learning is similar to hybrid/blended learning, but it allows students to choose their modality based on their needs and daily circumstances.

All of these modalities have digital teaching and learning elements, though technology-enhanced on-campus courses have minimal technology integration. The other five modalities rely heavily on digital teaching and learning.

Modality Characteristics On-campus

(technology-enhanced)Hybrid/

BlendedOnline Asynchronous Online Synchronous Online Bichronous HyFlex Teaching and learning occur in a physical classroom

X

X

X

Teaching and learning occur in a virtual environment

X

X

X

X

X

Teaching and learning occur in real time

X

X

X

X

X

Teaching and learning require digital technology infrastructure

X

X

X

X

X

X

Teaching and learning require digital support

X

X

X

X

X

X

With more institutions and programs offering online courses, students have more options. Students can now choose to complete courses and programs at any time and from any place. Higher education leaders, instructors, and learners have tested the efficiency and effectiveness of digital learning. Today, more institutions are open to these models of teaching and learning, though they might still be emerging in some contexts.

- Personnel and Support Services. The growing prevalence of digital teaching and learning in various instructional modalities requires additional investments in support services and personnel at universities and colleges. Some of the personnel and support services needed for successful digital transformation in the teaching and learning space are detailed below.Footnote11

- Instructional designers. Higher education institutions are hiring more instructional designers and technology specialists than in past years. Administrators and instructors have a better understanding and appreciation for instructional designers' expertise in digital learning design.Footnote12 Instructional designers partner with instructors to design effective courses for various modalities.

- Technology support specialists. More staff are needed to maintain networks and technology if an institution increases its digital teaching and learning offerings. Though technology support is already available on most campuses, the increase in digital teaching and learning has resulted in a need for 24/7 technology support for students and instructors. Research indicates that faculty are interested in receiving multifaceted support, including one-to-one and just-in-time support.Footnote13

- Academic and student support services. Academic support is needed so students can access library resources and writing centers. Student support services (registration, academic advising, study strategy consultations, etc.) are also needed for digital teaching and learning. Likewise, students with needs should have access to services that can assist them with digital learning.

- Incentives and recognition. Faculty need to be recognized and offered incentives and awards for being innovators in digital teaching.Footnote14 Financial incentives and course release time give faculty opportunities and time to explore and integrate digital innovations into their courses.

Support, services, incentives, and recognition motivate instructors to adopt innovative digital teaching methods.

- Organizational Policies and Planning. With any Dx effort, administrators must be prepared to lead digital teaching and learning initiatives and support general teaching and learning across subject areas. Leaders should continue using research-based practices in their decision-making and value digital teaching and learning innovations in all processes, including tenure and promotions.

- Policies and standards. Institutional policies and standards need to be set up for digital teaching and learning. Administrators need to consider a range of policies, such as teaching load, enrollment criteria, and performance and evaluation standards. For example, new course evaluation instruments should be created or adapted to evaluate digital teaching.

- Strategic planning. Strategic planning is "the process of defining a strategy as well as deciding on the resources that are allocated to pursue a strategy in order to achieve firms' goals."Footnote15 Administrators must integrate Dx into their strategic planning and get faculty buy-in.

- Funding models. Administrators should examine funding models for different modalities. Online courses provide opportunities for campuses to offer differential tuition rates since students do not have to be on campus or pay fees for campus-based resources.

- Equitable learning opportunities. Inequities in student access to technology were brought to light during the pandemic. Institutions should ensure that students have the hardware, software, and internet access they need to participate in online courses. Courses should also be accessible to students with cognitive and physical disabilities. Hence, policies and planning to reduce the digital divide are essential.

Overall, more policies are needed to support digital teaching and learning. Instructional leaders must also rethink any possible inequities related to digital teaching and learning, including funding, personnel, technology, and existing policies.

- Instructor Development. When the pandemic started, faculty who were new to online teaching had to adapt quickly. Many needed to participate in digital teaching and learning professional development activities. As Dx marches forward, training opportunities and resources for faculty development need to evolve based on faculty needs. These resources are aimed at improving faculty members' pedagogical and technological skills and their knowledge about accessibility, intellectual property, and online teaching best practices.

- Pedagogical and technological skills. Faculty should be given opportunities to develop their pedagogical and technological skills and learn how to integrate content. Faculty development professionals should continue to offer varied training on digital teaching and learning.

- Faculty beliefs. Faculty attitudes toward digital teaching and learning are evolving from reluctance to willingness. Professional development opportunities can support this evolution by focusing on teaching instructors how to establish positive value beliefs toward technology and digital teaching and how to align their teaching philosophies with digital teaching practices.Footnote16

- Accessibility. Accessible courses can benefit students with physical and cognitive disabilities. Faculty must be prepared to make their digital courses accessible. This takes additional time and effort and requires backing from administrators, technology support (e.g., closed captioning services), and instructional design support.Footnote17

- Intellectual property rights and copyright. During digital teaching, faculty need resources and support to become more familiar with intellectual property rights and the copyright of electronic materials.

When faculty switched to digital teaching and learning during the pandemic, many did not have adequate time to apply online teaching principles. Taking the time to rethink and apply pedagogical best practices will enhance the quality of online courses.

- Learner Development. Digital learning provides students with opportunities to learn in various modalities. This prepares them for the future workforce, where most jobs will require digital knowledge and skills.

- Computers and internet access. Students should have access to computers and the internet to be successful digital learners. Though many students have access to these tools, a digital divide still exists. Instructors and administrators must consider students' digital access before they engage in digital teaching.

- Time management and self-regulation. Digital learning comes with flexibility. This flexibility, however, puts greater reliance on self-regulated learning. For example, students have to learn to manage their time well, reduce distractions, and avoid procrastination during digital learning.Footnote18

- Instructional content and people. Students must be able to learn from a variety of content formats (text, audio, video) when instructors post lectures, podcasts, and discussions. They also must learn to engage with their instructor, peers, and content in a digital environment.

- Help. In a digital learning environment, students might be separated by distance, and they need to be able to reach out when they need help. Assistance could be provided by a technology help desk or an instructor.

- Community building. Students need opportunities to develop social communities and platforms for social interactions (e.g., online orientations, online social time for students to meet each other, etc.). Students will rely on their community to stay connected and engaged in digital learning.Footnote19

Technology resources, time management and self-regulation, engagement and help-seeking strategies, and community building help digital learners succeed.

- Partnerships. The pandemic highlighted the potential to leverage various partnerships to develop quality digital teaching and learning.

- Collaboration with other universities. Colleges and universities that already provided digital learning offered training and workshops to support instructors at other institutions. Expanding collaborations like these globally could strengthen digital teaching and learning worldwide.

- Collaboration with professional organizations. Professional organizations that are leaders in digital learning supported higher education institutions by offering training, workshops, and resources.

- Collaboration with industry. In some countries, industries outside of higher education partnered with institutions to provide access to the internet and electronic devices. Industry partnerships bring digital innovations to higher education institutions more quickly.

Partnerships with colleges and universities, professional organizations, and outside industries strengthen digital teaching and learning initiatives by capitalizing on the knowledge of experts in the space.

Conclusion

While our framework highlights seven distinct areas, achieving Dx for digital learning is an iterative process. As advanced digital technologies evolve, Dx initiatives will become commonplace for higher education institutions. Dx for digital learning brings flexibility and accessibility to students and prepares them to solve problems in the digital world. Dx efforts will continue to shape the norms and practices within higher education so that it adapts and evolves in parallel with society.

Notes

- Wahab Ali, "Online and Remote Learning in Higher Education Institutes: A Necessity in Light of COVID-19 Pandemic," Higher Education Studies 10, no. 3 (2020): 16–25; Florence Martin, Kui Xie, and Doris U. Bolliger, "Engaging Learners in the Emergency Transition to Online Learning during the COVID-19 Pandemic," supplement, Journal of Research on Technology in Education 54, S1 (2022): S1–S13; Ramona Maile Cutri, Juanjo Mena, and Erin Feinauer Whiting, "Faculty Readiness for Online Crisis Teaching: Transitioning to Online Teaching during the COVID-19 Pandemic," European Journal of Teacher Education 43, no. 4 (2020): 523–541. Jump back to footnote 1 in the text.

- Gregory Vial defined digital transformation as a process in which "digital technologies create disruptions triggering strategic responses from organizations that seek to alter their value creation paths while managing the structural changes and organizational barriers that affect the positive and negative outcomes of this process." See Gregory Vial, "Understanding Digital Transformation: A Review and a Research Agenda," The Journal of Strategic Information Systems 28, no. 2 (June 2019): 118; Susan Grajek and Betsy Reinitz, "Getting Ready for Digital Transformation: Change Your Culture, Workforce, and Technology," EDUCAUSE Review, July 8, 2019. Jump back to footnote 2 in the text.

- Ibid. Jump back to footnote 3 in the text.

- Kui Xie and N. Hawk, "Technology's Role and Place in Student Learning: What We Have Learned from Research and Theories," in Technology in School Classrooms: How It Can Transform Teaching and Student Learning Today, eds. J.G., Cibulka, & B.S. Cooper (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2017), 1–17. Jump back to footnote 4 in the text.

- Alice Gruber and Elwira Bauer, "Fostering Interaction in Synchronous Online Class Sessions with Foreign Language Learners," in Teaching, Technology, and Teacher Education during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Stories from the Field, eds. R.E. Ferdig, E. Baumgartner, R. Hartshorne, R. Kaplan-Rakowski, and C. Mouza (Waynesville, NC: Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education, 2020), 175–178. Jump back to footnote 5 in the text.

- Florence Martin and Anthony Karl Betrus, Digital Media for Learning, (Cham, Switzerland: Springer, 2019). Jump back to footnote 6 in the text.

- Tanya Joosten, Kate Lee-McCarthy, Lindsey Harness, and Ryan Paulus, Digital Learning Innovation Trends, research report, (Boston, MA: Online Learning Consortium, February 2020). Jump back to footnote 7 in the text.

- Christopher Hill and William Lawton, "Universities, the Digital Divide and Global Inequality," Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management 40, no. 6 (October 2018): 598–610; Kui Xie, Min Kyu Kim, Sheng-Lun Cheng, and Nicole C. Luthy, "Teacher Professional Development through Digital Content Evaluation," Educational Technology Research and Development 65, no. 4 (August 2017): 1067–1103; Kui Xie, Gennaro Di Tosto, Sheng-Bo Chen, and Vanessa W. Vongkulluksn, "A Systematic Review of Design and Technology Components of Educational Digital Resources," Computers & Education 127 (December 2018): 90–106. Jump back to footnote 8 in the text.

- Florence Martin, Drew Polly, and Albert Ritzhaupt, "Bichronous Online Learning: Blending Asynchronous and Synchronous Online Learning," EDUCAUSE Review, September 8, 2020. Jump back to footnote 9 in the text.

- Brian Beatty, "Hybrid Courses with Flexible Participation: The HyFlex Course Design," in Practical Applications and Experiences in K-20 Blended Learning Environments, eds. L. Kyei-Blankson and E. Ntuli (Hershey, PA: IGI Global, 2014), 153–177. Jump back to footnote 10 in the text.

- Swapna Kumar, Albert Ritzhaupt, and Neuza Sofia Pedro, "Development and validation of the Online Instructor Support Survey (OISS)," Online Learning 26, no. 1 (2022). Jump back to footnote 11 in the text.

- Yuan Chen and Saul Carliner, "A Special SME: An Integrative Literature Review of the Relationship Between Instructional Designers and Faculty in the Design of Online Courses for Higher Education," Performance Improvement Quarterly 33, no. 4 (2021): 471–495. Jump back to footnote 12 in the text.

- Drew Polly, Florence Martin, and T. Christa Guilbaud, "Examining Barriers and Desired Supports to Increase Faculty Members' Use of Digital Technologies: Perspectives of Faculty, Staff and Administrators," Journal of Computing in Higher Education 33, no. 1 (2021): 135–156. Jump back to footnote 13 in the text.

- Ibid. Jump back to footnote 14 in the text.

- Christian Matt, Thomas Hess, and Alexander Benlian, "Digital Transformation Strategies," Business & Information Systems Engineering 57, no. 5 (2015): 339–343. Jump back to footnote 15 in the text.

- Vanessa W. Vongkulluksn, Kui Xie, and Margaret A. Bowman, "The Role of Value on Teachers' Internalization of External Barriers and Externalization of Personal Beliefs for Classroom Technology Integration," Computers & Education 118 (2018): 70–81. Jump back to footnote 16 in the text.

- Thelma C. Guilbaud, Florence Martin, and Xiaoxia Newton, "Faculty Perceptions on Accessibility in Online Learning: Knowledge, Practice and Professional Development," Online Learning 25, no. 2 (2021): 6–35. Jump back to footnote 17 in the text.

- Sheng-Lun Cheng and Kui Xie, "Why College Students Procrastinate in Online Courses: A Self-Regulated Learning Perspective," The Internet and Higher Education 50 (2021): 100807. Jump back to footnote 18 in the text.

- Beith Oyarzun and Florence Martin, "A Case Study on Multi-modal Course Delivery and Social Learning Opportunities," Bulletin of the IEEE Technical Committee on Learning Technology 15, no. 1 (2013): 25–28. Jump back to footnote 19 in the text.

Florence Martin is a Professor of Learning, Design, and Technology at North Carolina State University.

Kui Xie is a Ted and Lois Cyphert Distinguished Professor and a Professor of Educational Psychology and Learning Technologies at The Ohio State University.

© 2022 Florence Martin and Kui Xie. The text of this work is licensed under a Creative Commons BY-SA 4.0 International License.