There is a general assumption among researchers (from West and East) that students in different learning contexts (deprived and developed) are searching information in different ways. Researchers in deprived context for example show a tendency to develop their own theory of educational technology based on this assumption. I myself got a conversation with a colleague researcher from the West who clearly said, “connectivism is too much to them”, referring to my study sample from Palestine.

This motivated me to conduct a firm qualitative research to see whether student’s search behavior differs between West and East. Information search behavior (ISB) has been studied heavily in the West, so I counted on the results reported on the literature and only gathered information from students from East (in this study, it was Palestine).

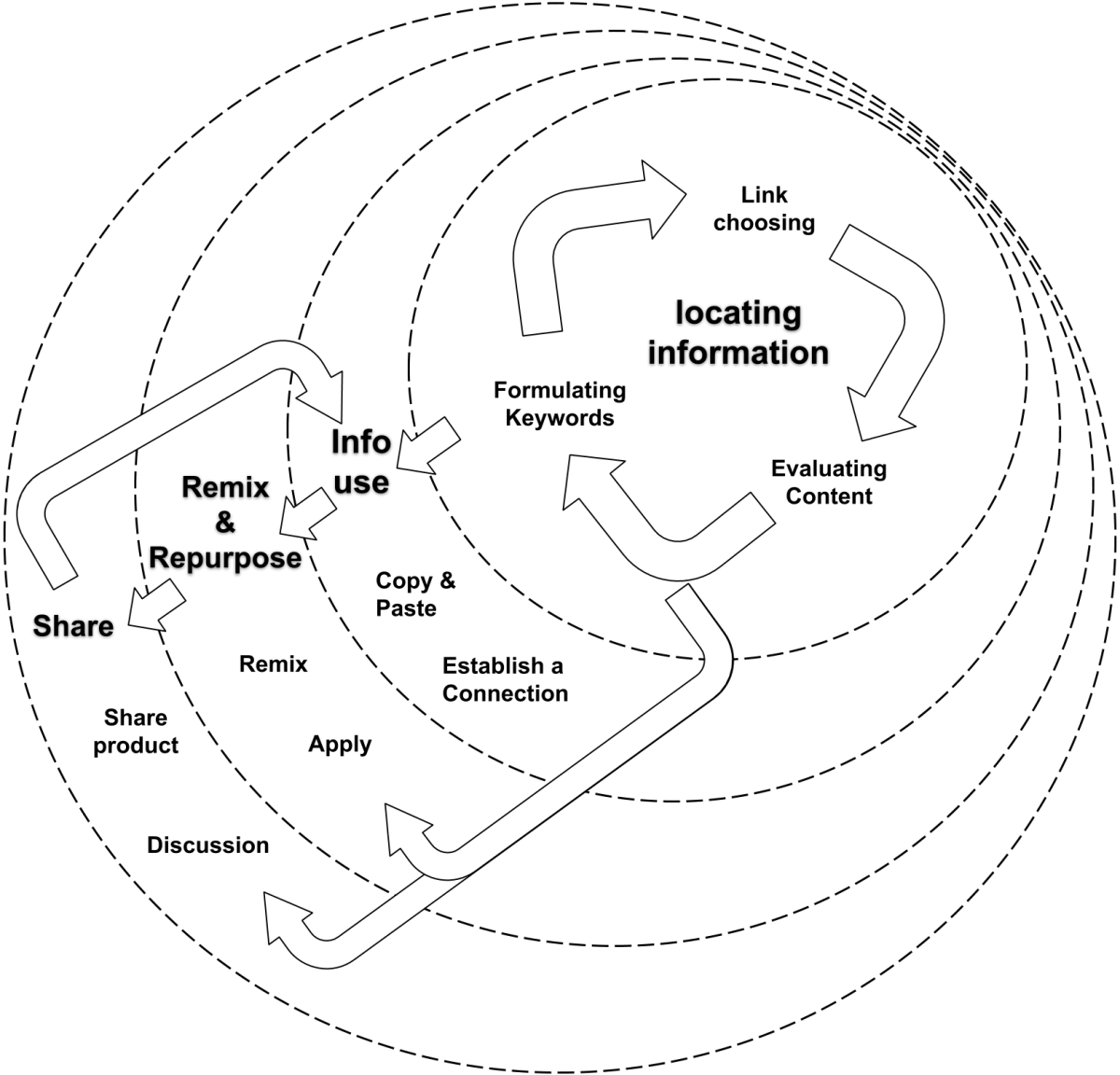

The main findings emerged from the study was that students in fragile contexts and in western countries search information similarly. The participants has followed the steps outlined on connectivism and digital literacy literature: 1) Locating information, 2) information use, 3) remix and repurpose, and

4) knowledge sharing

Students in fragile contexts and in western countries search information similarly.

However, I noticed that students in conflict-affected learning contexts plagiarize content heavily. This does not mean that plagiarism is not prevalent in western societies. It indeed does. But I found some extreme cases in this study which does not appear on any of the Westren studies I came across.

One interesting finding which I considered important and deserve much more consideration from researchers from West and East alike is the meta-search behavior.

Meta-search is a key theme to develop digital competencies in higher education

For most of the participants, the Internet is a big repository full of useful resources, where their only job is to formulate the right keywords to fetch those

resources. While the Internet is indeed so, a more comprehensive view conceives the Internet as a means to develop one’s searching skills. In this study, the term meta-search was coined to refer to searching-about searching

behavior. It is meta because it does not pertain directly to the subject matter. Rather, it resides in a higher level of searching which directs and manages how one should search. From this perspective, one does not need to teach learners digital competences (which are renewable); one needs to change their representations about the Internet.

The study argues that critical and cyberliteracy are perhaps the nominated theoretical frameworks for developing information search mechanisms in oppressed societies.

I believe that critical and cyberliteracy are perhaps the nominated theoretical frameworks for developing information search mechanisms in oppressed societies. The critical literacy emphasizes the importance of the circumferences, history, and environment of ISB. It is not the text that matters, but the hidden motives of writing the text (who does it benefit or impair), the awareness of oneself throughout the reading experience (how one was and how one became), and the social context that produced the text. Students need to read the world, not the text, and challenge the author and the reality. Cyberliteracy extends critical literacy for online communication, to include issues such as recognizing online threats or hidden intentions (e.g. virus, malware, trojan and phishing software, advertisements, spam, fake news and deception), strengthening one’s immune system against any attack, and maintaining other’s privacy (Lazer et al., 2018; Mackey & Jacobson, 2011). In other words, students are asked to cleverly and ethically participate in learning networks.

References

AlDahdouh, A. A. (2021). Information search behavior in fragile and conflict-affected learning contexts. The Internet and Higher Education, 50, 100808. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2021.100808

AlDahdouh, A. A., Osório, A. J., & Caires, S. (2015). Understanding knowledge network, learning and connectivism. International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning, 12(10), 3–21. http://www.itdl.org/Journal/Oct_15/Oct15.pdf#page=7

Lazer, D. M. J., Baum, M. A., Benkler, Y., Berinsky, A. J., Greenhill, K. M., Menczer, F., … Zittrain, J. L. (2018). The science of fake news. Science, 359(6380), 1094–1096. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aao2998.

Mackey, T. P., & Jacobson, T. E. (2011). Reframing information literacy as a metaliteracy. College & Research Libraries, 72(1), 62–78. https://doi.org/10.5860/crl-76r1

One thought on “Search Behavior: does context make difference?”