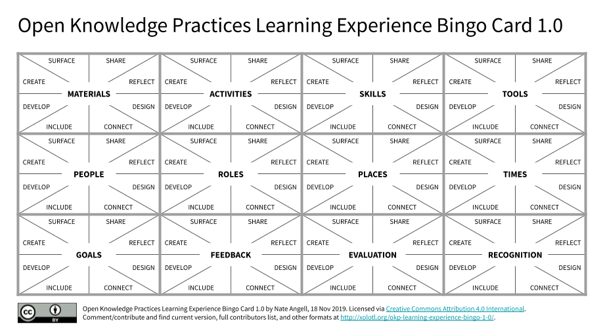

After getting a lot of really helpful feedback on the Open Knowledge Practices Learning Experience Rubric 1.1 (OKPLER 1.1), I’ve tried to transform it into a resource that incorporates the fantastic contributions from other folks and still provides a tool we might use to think about the “openness” of learning experiences. The biggest change is from the format of a rubric to more of a mapping tool, that I’ve been thinking of as a sort of “bingo card”.

TL;DR: The new bingo card for open learning experiences is quite a bit different than the rubric, both simpler and, underneath, more complex. Read on to learn more.

I got clear feedback that a rubric model itself has issues — especially in the open education context — and I’ll admit I have a conflicted relationship with rubrics anyway. On one hand, I like the way rubrics can be used to surface expected outcomes and levels of demonstration/proficiency. But on the other hand, I don’t like the way rubrics can foreclose outcomes — what if something cool happens the rubric doesn’t expect? — and can attach questionably quantified values to participation — is doing this really worth more than doing that? People who actually know how to make good rubrics probably avoid these pitfalls, but I did not with the OKPLER 1.1 and so I’ve attempted to recast it as a bingo card.

While the rubric was maybe attempting to answer a question like: “How open is this learning experience?” I’m hoping this bingo card and its future augmentations can help people answer a fundamentally different question: “What dimensions of openness does this learning experience incorporate and generate?” If the bingo card does help answer that kind of question, then I’m hoping it can be used to help people think how experiences can be opened more rather than just cataloging and judging their openness. I may have created a monster, so I’m looking forward to your feedback on how to make the bingo card better or maybe move to yet another model that could be even more helpful.

Yes, the bingo card looks complicated. Let me explain how it got this way, and also how there’s a simpler model embedded in all the words and lines.

Please comment and contribute! Highlight any text on this page to add Hypothesis annotations, add comments or webmentions below, and/or contact me. I’ll be including all those who contribute in the acknowledgements (unless they prefer to remain unacknowledged).

You can access a Google Slides version of the full bingo card that can be downloaded in various other formats, including a PDF suitable for printing.

Learning experience ingredients

I started this whole project with the idea that learning experiences include ingredients, like materials, tools, people, assessments, etc. I also started with the idea that, in general, open educational practices attempt to open up the ways in which those ingredients might be boxed in.

For example, a materials ingredient in a learning experience might be an educational resource like a textbook. If you apply open practices to the materials box containing a textbook, you might “open” the box by using an openly-licensed textbook. You might also add openness to the materials in the box by having the participants revise or create materials. You might add openness to the box by having participants share materials they’ve worked on more broadly. I’m not so interested in which of these practices is more open or better than the others, but I am interested in being able to identify which open practices are involved and imagining how others might be added.

So that’s how the bingo card ends up having all these boxes: materials, activities, skills, tools, people, roles, places, times, goals, feedback, evaluation, recognition. These are some ingredients one might find in a learning experience. There may be others too. That’s where the bingo card is great because you could just keep adding boxes for other ingredients. The simple version of the bingo card is just these boxes, where you consider the openness of a learning experience in relation to each box with the answer to a simple question: Does this experience open this box of ingredients?

Materials

Materials used in the experience. |

Activities

Activities people participate in during the experience. |

Skills

Skills people use during the experience. |

Tools

Tools people use during the experience. |

People

People that design and/or participate in the experience. |

Roles

Roles people play in the experience. |

Places

Places where the experience happens. |

Times

Times when the experience happens. |

Goals

Goals the experience seeks to fulfill. |

Feedback

Feedback the experience offers to participants. |

Evaluation

Evaluations of participation in the experience (eg, course surveys, grades, teacher evaluations). |

Recognition

Recognitions of participation in the experience (eg, badges, certification, credit). |

OKP Learning Experience Bingo 1.0

Access a Google Slides version of this simplified bingo card that can be downloaded in various other formats, including a PDF suitable for printing.

Dimensions of openness

That’s the simple version, but what’s with all the little words inside each box? Beyond the basic question of whether any particular box IS being “opened” in a learning experience, there’s the question of HOW it’s being opened.

Based on the early work of the OKPLER 1.1 and the feedback it received, certain “dimensions” of openness started to crystallize and many folks suggested also including dimensions of learning design, open or not. The pie slices radiating out from each ingredient box represent these dimensions of openness/learning design. The dimensions radiate from the center — again — to avoid the idea of hierarchy. An ingredient might be expanding along one dimension and not another (eg, a skill in a learning experience might be developed but not reflected upon), but the bingo card does not seek to measure whether one dimension of openness/learning design is better or more important than another. You could also add other dimensions as new pie slices to expand beyond the eight dimensions in version 1.0.

I’d especially like to thank Apurva Ashok, Maha Bali, Rajiv Jhangiani, Remi Kalir, and Robin DeRosa for helping me think through how to include dimensions of inclusiveness and design. These dimensions are still perhaps more abstract than some contributors might want, but I’m hoping this bingo card foregrounds the centrality of thinking about who is included in educational experiences and how educational experiences are designed.

The dimensions in the boxes are abbreviated, so here’s a 1.0 draft of a key. I’ve also presented some examples, but I’m not entirely sure every dimension works in every ingredient box, so I welcome new ingredients, dimensions, and examples:

- Surface: Are ingredients in the box surfaced in the experience (which I see as a prerequisite for their opening)? For example: Are the roles people play in the experience clearly articulated?

- Share: Are ingredients in the box shared with others? (Note: I’m not building in any judgement here about how ingredients are shared (eg, with an open license) as I believe the nuances of sharing are complex, depend on context, and sharing in any way is an opening). For example:

- Are the materials or tools used and/or created in the experience made public?

- Are the materials or tools used and/or created in the experience openly licensed?

- Create: Do participants create/revise/remix ingredients in the box? For example:

- Do participants change the places where the experience happens?

- Do participants create/remix/revise materials in the experience?

- Are participants involved in creating the processes used to evaluate their work?

- Develop: Are ingredients in the box developed by the participants? For example: Do participants modify/extend activities in the experience?

- Reflect: Do participants reflect on ingredients in the box during the experience? This is the meta-cognitive dimension: Does the experience enable participants to think about how they are participating? (Special thanks to Rajiv Jhangiani for augmenting this dimension.) For example:

- Do participants reflect on the goals of the experience, how they engaged in them, and/or how the goals might be different/better for themselves or others?

- Design: Is the design process of the ingredients in the box itself open? This is the dimension that explores the openness of how the experience was designed. (Special thanks to Apurva Ashok and Maha Bali for helping me think through this dimension.) For example: Did the people designing the experience represent different experiences and points of view?

- Include: Do ingredients in the box engage other people? (Special thanks to Maha Bali and Remi Kalir for helping me think through this dimension.) For example:

- Are marginalized people engaged purposefully as a part of the experience?

- Do materials provide space for perspectives they do not already represent?

- Does the timing of the experience enable participation by people in other timezones?

- Connect: Do ingredients in the box connect outward, increasing their audience, impact, lifespan, intertextuality, etc? (Special thanks to Rajiv Jhangiani for pointing to the work of Seraphin et al to help augment this dimension.) For example:

- Do the materials created by participants have value for a wider audience outside the context of the experience?

- Might activities disseminated by the participants fruitfully engage other people for some time outside the context of the experience itself?

- Do the goals of the experience connect to participants’ other activities/goals beyond the experience?

Putting bingo into practice

I imagine people using this bingo card by holding it up to a learning experience and checking off the areas where the experience is opening. I’ve tried it myself with a few of the open learning experiences collected in the Open Pedagogy Notebook and found it to be productive. With a specific experience, I’m able to check off dimensions of openness it includes for certain ingredients, but am also able to see other ingredients and dimensions where it could explore openness further.

I hope that as this project of rubrics and bingo cards matures, we may get to a place where holding it up to learning experiences helps increase our understandings and thoughtfulness about how openness happens.

Contributors: OKP Learning Experience Bingo 1.0

Bibliography: Open Learning Experience Design

Resources listed below are items in the larger, public Open Knowledge Practices Zotero group bibliography that appear in the subcollection, Learning Experience Bingo.

Let me know if you have a resource to add to this bibliography or send me your email address if you would like to join the collaborative Zotero group to add and tag resources yourself.

1561563

okp,ler

items

0

author

asc

1586

https://xolotl.org/wp-content/plugins/zotpress/

%7B%22status%22%3A%22success%22%2C%22updateneeded%22%3Afalse%2C%22instance%22%3A%22zotpress-1b4d2ae905906bf358ba8e6aa5da3bd7%22%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22request_last%22%3A0%2C%22request_next%22%3A0%2C%22used_cache%22%3Atrue%7D%2C%22data%22%3A%5B%7B%22key%22%3A%22QPVXMHTW%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A1561563%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Bali%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222017-04-21%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A0%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3EBali%2C%20Maha.%20%26%23x201C%3BCuration%20of%20Posts%20on%20Open%20Pedagogy%20%23YearOfOpen.%26%23x201D%3B%20%3Ci%3EReflecting%20Allowed%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%2C%2021%20Apr.%202017%2C%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fblog.mahabali.me%5C%2Fwhyopen%5C%2Fcuration-of-posts-on-open-pedagogy-yearofopen%5C%2F%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fblog.mahabali.me%5C%2Fwhyopen%5C%2Fcuration-of-posts-on-open-pedagogy-yearofopen%5C%2F%3C%5C%2Fa%3E.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22blogPost%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Curation%20of%20Posts%20on%20Open%20Pedagogy%20%23YearOfOpen%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Maha%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Bali%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22In%20preparation%20for%20Monday%5Cu2019s%20Open%20Pedagogy%20Hangout%20%28see%20announcement%20here%5Cu00a0%5Cu2013%20includes%20list%20of%20guests%20and%20YouTube%20watch%20link%29%20I%5Cu00a0thought%20it%20might%20be%20useful%20to%20roughly%20curate%20some%20%5Cu2026%22%2C%22blogTitle%22%3A%22Reflecting%20Allowed%22%2C%22date%22%3A%222017-04-21T10%3A37%3A17%2B00%3A00%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fblog.mahabali.me%5C%2Fwhyopen%5C%2Fcuration-of-posts-on-open-pedagogy-yearofopen%5C%2F%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22QJKN5G4N%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222019-12-01T20%3A29%3A47Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22XTGKCIBZ%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A1561563%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Bali%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222017-04-20%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3EBali%2C%20Maha.%20%26%23x201C%3BWhat%20Is%20Open%20Pedagogy%3F%20%23YearOfOpen%20Hangout%20April%2024.%26%23x201D%3B%20%3Ci%3EReflecting%20Allowed%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%2C%2020%20Apr.%202017%2C%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fblog.mahabali.me%5C%2Fwhyopen%5C%2Fwhat-is-open-pedagogy-yearofopen-hangout-april-24%5C%2F%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fblog.mahabali.me%5C%2Fwhyopen%5C%2Fwhat-is-open-pedagogy-yearofopen-hangout-april-24%5C%2F%3C%5C%2Fa%3E.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22blogPost%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22What%20is%20Open%20Pedagogy%3F%20%23YearOfOpen%20hangout%20April%2024%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Maha%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Bali%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22What%20is%20Open%20Pedagogy%3F%20Who%20gets%20to%20define%20what%20open%20pedagogy%20is%2C%20and%20how%20does%20that%20affect%20all%20of%20us%20who%20call%20what%20we%20practice%20%5Cu201copen%20pedagogy%5Cu201d%3F%20I%20was%20invited%20to%20submit%20my%20answer%20to%20that%20question%20by%20the%20OEConsortium%20for%20%23YearOfOpen%20a%20while%20ago%2C%20and%20I%20submitted%20it%20before%20my%20trip%20to%20London%20to%20OER17.%20During%20%23OER17%2C%20my%20response%2C%20as%20well%20as%20others%5Cu2019%2C%20was%20published%20here.%20My%20feeling%20was%20that%3A%20A%20discussion%20among%20open%20pedagogy%20advocates%20and%20practitioners%20was%20needed%20beyond%20these%20statements.%20More%20diversity%20of%20voices%20on%20the%20matter%20are%20needed.%20David%20Wiley%5Cu2019s%20contribution%20is%20controversial%20imho%20and%20I%20wanted%20an%20opportunity%20to%20discuss%20a%20variety%20of%20approaches.%20Hence%20the%20hangout%20I%20am%20announcing%20here.%20I%20have%20lots%20of%20complicated%20feelings%20about%20this%20topic%2C%20and%20I%20have%20invited%20a%20bunch%20of%20%28relatively%29%20diverse%20folks%20to%20discuss%20this%20topic%20as%20part%20of%20%23YearOfOpen.%22%2C%22blogTitle%22%3A%22Reflecting%20Allowed%22%2C%22date%22%3A%222017-04-20T08%3A29%3A37%2B00%3A00%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fblog.mahabali.me%5C%2Fwhyopen%5C%2Fwhat-is-open-pedagogy-yearofopen-hangout-april-24%5C%2F%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22QJKN5G4N%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222019-12-02T19%3A08%3A40Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%225C8T5LST%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A1561563%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Baroud%20et%20al.%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3EBaroud%2C%20Fawzi%2C%20et%20al.%20%26%23x201C%3BWhat%20Is%20Open%20Education%3F%26%23x201D%3B%20%3Ci%3EYear%20of%20Open%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%2C%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.yearofopen.org%5C%2Fwhat-is-open-education%5C%2F%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.yearofopen.org%5C%2Fwhat-is-open-education%5C%2F%3C%5C%2Fa%3E.%20Accessed%202%20Dec.%202019.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22blogPost%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22What%20is%20Open%20Education%3F%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Fawzi%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Baroud%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Glenda%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Cox%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Allen%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Rao%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Peter%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Smith%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Sophie%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Touze%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22blogTitle%22%3A%22Year%20of%20Open%22%2C%22date%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.yearofopen.org%5C%2Fwhat-is-open-education%5C%2F%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en-US%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22QJKN5G4N%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222019-12-02T19%3A07%3A51Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22A9EXMJ8G%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A1561563%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Cormier%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222019-03-24%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3ECormier%2C%20David.%20%3Ci%3EOpen%20Pedagogy%20%26%23x2013%3B%20A%20Three%20Day%20Seminar%20at%20Digital%20Pedagogy%20Lab%3C%5C%2Fi%3E.%2024%20Mar.%202019%2C%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27http%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fdavecormier.com%5C%2Fedblog%5C%2F2019%5C%2F03%5C%2F24%5C%2Fopen-pedagogy-a-three-day-seminar-at-digital-pedagogy-lab%5C%2F%27%3Ehttp%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fdavecormier.com%5C%2Fedblog%5C%2F2019%5C%2F03%5C%2F24%5C%2Fopen-pedagogy-a-three-day-seminar-at-digital-pedagogy-lab%5C%2F%3C%5C%2Fa%3E.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22blogPost%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Open%20Pedagogy%20%5Cu2013%20A%20three%20day%20seminar%20at%20Digital%20Pedagogy%20Lab%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22David%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Cormier%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22blogTitle%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%222019-03-24%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22http%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fdavecormier.com%5C%2Fedblog%5C%2F2019%5C%2F03%5C%2F24%5C%2Fopen-pedagogy-a-three-day-seminar-at-digital-pedagogy-lab%5C%2F%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22QJKN5G4N%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222019-12-01T20%3A29%3A47Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22QQ336HNK%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A1561563%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Cronin%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222017-08-15%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A2%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3ECronin%2C%20Catherine.%20%26%23x201C%3BOpenness%20and%20Praxis%3A%20Exploring%20the%20Use%20of%20Open%20Educational%20Practices%20in%20Higher%20Education.%26%23x201D%3B%20%3Ci%3EThe%20International%20Review%20of%20Research%20in%20Open%20and%20Distributed%20Learning%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%2C%20vol.%2018%2C%20no.%205%2C%20Aug.%202017%2C%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27http%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.irrodl.org%5C%2Findex.php%5C%2Firrodl%5C%2Farticle%5C%2Fview%5C%2F3096%27%3Ehttp%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.irrodl.org%5C%2Findex.php%5C%2Firrodl%5C%2Farticle%5C%2Fview%5C%2F3096%3C%5C%2Fa%3E.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22journalArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Openness%20and%20Praxis%3A%20Exploring%20the%20Use%20of%20Open%20Educational%20Practices%20in%20Higher%20Education%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Catherine%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Cronin%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%222017%5C%2F08%5C%2F15%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%221492-3831%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22http%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.irrodl.org%5C%2Findex.php%5C%2Firrodl%5C%2Farticle%5C%2Fview%5C%2F3096%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22QJKN5G4N%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222020-01-03T18%3A22%3A29Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22M9D8E8SN%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A1561563%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22DeRosa%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222017-04-24%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3EDeRosa%2C%20Robin.%20%26%23x201C%3BOpen%20Pedagogy%3A%20Quick%20Reflection%20for%20%23YearOfOpen.%26%23x201D%3B%20%3Ci%3EActualham%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%2C%2024%20Apr.%202017%2C%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27http%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Frobinderosa.net%5C%2Funcategorized%5C%2F1775%5C%2F%27%3Ehttp%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Frobinderosa.net%5C%2Funcategorized%5C%2F1775%5C%2F%3C%5C%2Fa%3E.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22blogPost%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Open%20Pedagogy%3A%20Quick%20Reflection%20for%20%23YearOfOpen%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Robin%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22DeRosa%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22Open%20Pedagogy.%20I%5Cu2019m%20taking%20a%2015-minute%20break%20in%20a%20busy%20afternoon%20to%20sketch%20out%20some%20thoughts%20ahead%20of%20the%20%23YearOfOpen%20hangout%20happening%20in%20a%20few%20minutes.%20Access.%22%2C%22blogTitle%22%3A%22actualham%22%2C%22date%22%3A%222017-04-24T19%3A53%3A22%2B00%3A00%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22http%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Frobinderosa.net%5C%2Funcategorized%5C%2F1775%5C%2F%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en-US%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22QJKN5G4N%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222019-12-02T19%3A08%3A27Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%223VSENUXR%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A1561563%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22DeRosa%20and%20Jhangiani%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222018-03-16%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3EDeRosa%2C%20Robin%2C%20and%20Rajiv%20Jhangiani.%20%26%23x201C%3BOpen%20Pedagogy%20Notebook.%26%23x201D%3B%20%3Ci%3EOpen%20Pedagogy%20Notebook%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%2C%2016%20Mar.%202018%2C%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27http%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fopenpedagogy.org%5C%2Fopen-pedagogy%5C%2F%27%3Ehttp%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fopenpedagogy.org%5C%2Fopen-pedagogy%5C%2F%3C%5C%2Fa%3E.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22webpage%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Open%20Pedagogy%20Notebook%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Robin%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22DeRosa%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Rajiv%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Jhangiani%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22There%20are%20many%20ways%20to%20begin%20a%20discussion%20of%20%5Cu201cOpen%20Pedagogy.%5Cu201d%20Although%20providing%20a%20framing%20definition%20might%20be%20the%20obvious%20place%20to%20start%2C%20we%20want%20to%20resist%20that%20for%20just%20a%20moment%20to%20ask%20a%20set%20of%20related%20questions%3A%20What%20are%20your%20hopes%20for%20education%2C%20particularly%20for%20higher%20education%3F%20What%20vision%20do%20you%20work%20toward%20when%20you%20design%20your%20daily%20professional%20practices%20in%20and%20out%20of%20the%20classroom%3F%20How%20do%20you%20see%20the%20roles%20of%20the%20learner%20and%20the%20teacher%3F%20What%20challenges%20do%20your%20students%20face%20in%20their%20learning%20environments%2C%20and%20how%20does%20your%20pedagogy%20address%20them%3F%22%2C%22date%22%3A%222018-03-16T16%3A44%3A09%2B00%3A00%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22http%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fopenpedagogy.org%5C%2Fopen-pedagogy%5C%2F%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22QJKN5G4N%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222019-12-01T20%3A29%3A47Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22Y4Z2MLT6%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A1561563%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Hodgkinson-Williams%20and%20Trotter%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222018-11-19%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A4%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3EHodgkinson-Williams%2C%20Cheryl%20Ann%2C%20and%20Henry%20Trotter.%20%26%23x201C%3BA%20Social%20Justice%20Framework%20for%20Understanding%20Open%20Educational%20Resources%20and%20Practices%20in%20the%20Global%20South.%26%23x201D%3B%20%3Ci%3EJournal%20of%20Learning%20for%20Development%20-%20JL4D%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%2C%20vol.%205%2C%20no.%203%2C%20Nov.%202018%2C%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27http%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fjl4d.org%5C%2Findex.php%5C%2Fejl4d%5C%2Farticle%5C%2Fview%5C%2F312%27%3Ehttp%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fjl4d.org%5C%2Findex.php%5C%2Fejl4d%5C%2Farticle%5C%2Fview%5C%2F312%3C%5C%2Fa%3E.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22journalArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22A%20Social%20Justice%20Framework%20for%20Understanding%20Open%20Educational%20Resources%20and%20Practices%20in%20the%20Global%20South%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Cheryl%20Ann%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Hodgkinson-Williams%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Henry%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Trotter%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22At%20the%20heart%20of%20the%20open%20educational%20resources%20%28OER%29%20movement%20is%20the%20intention%20to%20provide%20affordable%20access%20to%20culturally%20relevant%20education%20to%20all.%20This%20imperative%20could%20be%20described%20as%20a%20desire%20to%20provide%20education%20in%20a%20manner%20consistent%20with%20social%20justice%20which%2C%20according%20to%20Fraser%20%282005%29%2C%20is%20understood%20as%20%5Cu201cparity%20of%20participation%5Cu201d.%20Drawing%20on%20her%20concept%20of%20social%20justice%2C%20we%20suggest%20a%20slight%20modification%20of%20Fraser%5Cu2019s%20framework%20for%20critically%20analysing%20ways%20in%20which%20the%20adoption%20and%20impact%20of%20OER%20and%20their%20undergirding%20open%20educational%20practices%20%28OEP%29%20might%20be%20considered%20socially%20just.%20We%20then%20provide%20illustrative%20examples%20from%20the%20cross-regional%20Research%20on%20Open%20Educational%20Resources%20for%20Development%20%28ROER4D%29%20project%20%282014-2017%29%20to%20show%20how%20this%20framework%20can%20assist%20in%20determining%20in%20what%20ways%2C%20if%20at%20all%2C%20the%20adoption%20of%20OER%20and%20enactment%20of%20OEP%20have%20responded%20to%20economic%20inequalities%2C%20cultural%20inequities%20and%20political%20exclusions%20in%20education.%20Furthermore%2C%20we%20employ%20Fraser%5Cu2019s%20%282005%29%20concepts%20to%20identify%20whether%20these%20social%20changes%20are%20either%20%5Cu201caffirmative%5Cu201d%20%28i.e.%2C%20ameliorative%29%20or%20%5Cu201ctransformative%5Cu201d%20in%20their%20economic%2C%20cultural%20and%20political%20effects%20in%20the%20Global%20South%20education%20context.%22%2C%22date%22%3A%222018%5C%2F11%5C%2F19%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%222311-1550%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22http%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fjl4d.org%5C%2Findex.php%5C%2Fejl4d%5C%2Farticle%5C%2Fview%5C%2F312%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22QJKN5G4N%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222020-01-03T18%3A22%3A31Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22CI4AMKQU%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A1561563%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Inamorato%20%20dos%20%20Santos%20et%20al.%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222016-07-27%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3EInamorato%26%23xA0%3B%20dos%26%23xA0%3B%20Santos%2C%20Andreia%2C%20et%20al.%20%3Ci%3EOpening%20up%20Education%3A%20A%20Support%20Framework%20for%20Higher%20Education%20Institutions%3C%5C%2Fi%3E.%20Text%2C%20Publications%20Office%20of%20the%20European%20Union%2C%2027%20July%202016%2C%20p.%2078%2C%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fec.europa.eu%5C%2Fjrc%5C%2Fen%5C%2Fpublication%5C%2Feur-scientific-and-technical-research-reports%5C%2Fopening-education-support-framework-higher-education-institutions%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fec.europa.eu%5C%2Fjrc%5C%2Fen%5C%2Fpublication%5C%2Feur-scientific-and-technical-research-reports%5C%2Fopening-education-support-framework-higher-education-institutions%3C%5C%2Fa%3E.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22report%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Opening%20up%20Education%3A%20A%20Support%20Framework%20for%20Higher%20Education%20Institutions%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Andreia%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Inamorato%20%20dos%20%20Santos%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Yves%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Punie%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Jonatan%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Casta%5Cu00f1o-Mu%5Cu00f1oz%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22This%20report%20presents%20a%20support%20framework%20for%20higher%20education%20institutions%20%28HEIs%29%20to%20open%20up%20education.%20This%20framework%20proposes%20a%20wide%20definition%20of%20the%20term%20%5Cu2018open%20education%5Cu2019%2C%20which%20accommodates%20different%20uses%2C%20in%20order%20to%20promote%20transparency%20and%20a%20holistic%20approach%20to%20practice.%20It%20goes%20beyond%20OER%2C%20MOOCs%20and%20open%20access%20to%20embrace%2010%20dimensions%20of%20open%20education.%20The%20framework%20can%20be%20used%20as%20a%20tool%20by%20HEI%20staff%20to%20help%20them%20think%20through%20strategic%20decisions%3A%20pedagogical%20approaches%2C%20collaboration%20between%20individuals%20and%20institutions%2C%20recognition%20of%20non-formal%20learning%20and%20different%20ways%20of%20making%20content%20available.%20Contemporary%20open%20education%20is%20mostly%20enabled%20by%20ICTs%20and%20because%20of%20this%2C%20there%20is%20almost%20limitless%20potential%20for%20innovation%20and%20reach%2C%20which%20in%20turn%20contributes%20to%20the%20modernisation%20of%20higher%20education%20in%20Europe.%22%2C%22reportNumber%22%3A%22%22%2C%22reportType%22%3A%22Text%22%2C%22institution%22%3A%22Publications%20Office%20of%20the%20European%20Union%22%2C%22date%22%3A%222016-07-27T09%3A09%3A55%2B02%3A00%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fec.europa.eu%5C%2Fjrc%5C%2Fen%5C%2Fpublication%5C%2Feur-scientific-and-technical-research-reports%5C%2Fopening-education-support-framework-higher-education-institutions%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22QJKN5G4N%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222019-12-01T20%3A29%3A47Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22F3GLWE5U%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A1561563%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Lambert%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222018-11-19%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A2%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3ELambert%2C%20Sarah%20Roslyn.%20%26%23x201C%3BChanging%20Our%20%28Dis%29Course%3A%20A%20Distinctive%20Social%20Justice%20Aligned%20Definition%20of%20Open%20Education.%26%23x201D%3B%20%3Ci%3EJournal%20of%20Learning%20for%20Development%20-%20JL4D%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%2C%20vol.%205%2C%20no.%203%2C%20Nov.%202018%2C%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fjl4d.org%5C%2Findex.php%5C%2Fejl4d%5C%2Farticle%5C%2Fview%5C%2F290%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fjl4d.org%5C%2Findex.php%5C%2Fejl4d%5C%2Farticle%5C%2Fview%5C%2F290%3C%5C%2Fa%3E.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22journalArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Changing%20our%20%28Dis%29Course%3A%20A%20Distinctive%20Social%20Justice%20Aligned%20Definition%20of%20Open%20Education%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Sarah%20Roslyn%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Lambert%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22This%20paper%20investigates%20the%20degree%20to%20which%20recent%20digital%20Open%20Education%20literature%20is%20aligned%20to%20social%20justice%20principles%2C%20starting%20with%20the%20first%20UNESCO%20definition%20of%20Open%20Educational%20Resources%20%28OER%29.%20A%20critical%20analysis%20of%2019%20texts%20was%20undertaken%20to%20track%20dominant%20and%20alternative%20ideas%20shaping%20the%20development%20of%20Open%20Education%20since%202002%20as%20it%20broadened%20and%20developed%20from%20OER%20to%20Open%20Educational%20Practices%20%28OEP%29.%20The%20paper%20begins%20by%20outlining%20the%20method%20of%20texts%20selection%2C%20including%20defining%20the%20three%20principles%20of%20social%20justice%20%28redistributive%2C%20recognitive%20and%20representational%20justice%29%20used%20as%20an%20analytical%20lens.%20Next%20the%20paper%20sets%20out%20findings%20which%20show%20where%20and%20how%20the%20principles%20of%20social%20justice%20became%20lost%20within%20the%20details%20of%20texts%2C%20or%20in%20other%20digital%20agendas%20and%20technological%20determinist%20debates.%20Finally%2C%20a%20new%20social%20justice%20aligned%20definition%20for%20Open%20Education%20is%20offered.%20The%20aim%20of%20the%20new%20definition%20is%20to%20provide%20new%20language%20and%20a%20strong%20theoretical%20framework%20for%20equitable%20education%2C%20as%20well%20as%20to%20clearly%20distinguish%20the%20field%20of%20Open%20Education%20from%20mainstream%20constructivist%20eLearning.%22%2C%22date%22%3A%222018%5C%2F11%5C%2F19%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%222311-1550%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fjl4d.org%5C%2Findex.php%5C%2Fejl4d%5C%2Farticle%5C%2Fview%5C%2F290%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22QJKN5G4N%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222019-12-02T20%3A58%3A28Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%226J5AXQB6%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A1561563%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22McVerry%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222019-11-01%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3EMcVerry%2C%20Greg.%20%26%23x201C%3BDraft%20Framework%20for%20Effective%20Teaching%20and%20Higher%20Ed.%26%23x201D%3B%20%3Ci%3EINTERTEXTrEVOLUTION%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%2C%201%20Nov.%202019%2C%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fjgregorymcverry.com%5C%2Fframeworkforeffectivehighered%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fjgregorymcverry.com%5C%2Fframeworkforeffectivehighered%3C%5C%2Fa%3E.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22webpage%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Draft%20Framework%20for%20Effective%20Teaching%20and%20Higher%20Ed%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Greg%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22McVerry%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%2211%5C%2F1%5C%2F2019%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fjgregorymcverry.com%5C%2Fframeworkforeffectivehighered%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22QJKN5G4N%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222019-12-01T20%3A29%3A47Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22J6UXYVQT%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A1561563%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Online%20Learning%20Consortium%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3EOnline%20Learning%20Consortium.%20%26%23x201C%3BOLC%20Quality%20Scorecard%3A%20Improve%20the%20Quality%20of%20Online%20Learning%20%26amp%3B%20Teaching.%26%23x201D%3B%20%3Ci%3EOnline%20Learning%20Consortium%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%2C%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fonlinelearningconsortium.org%5C%2Fconsult%5C%2Folc-quality-scorecard-blended-learning-programs%5C%2F%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fonlinelearningconsortium.org%5C%2Fconsult%5C%2Folc-quality-scorecard-blended-learning-programs%5C%2F%3C%5C%2Fa%3E.%20Accessed%2025%20Nov.%202019.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22webpage%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22OLC%20Quality%20Scorecard%3A%20Improve%20the%20Quality%20of%20Online%20Learning%20%26%20Teaching%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22name%22%3A%22Online%20Learning%20Consortium%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22The%20OLC%20Quality%20Scorecard%20-%20Benchmarking%20Tools%2C%20Checklists%2C%20%26%20Rubrics%20for%20Evaluating%20the%20Quality%20and%20Effectiveness%20of%20Online%20Learning%20Programs%20%26%20Courses%22%2C%22date%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fonlinelearningconsortium.org%5C%2Fconsult%5C%2Folc-quality-scorecard-blended-learning-programs%5C%2F%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en-US%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22QJKN5G4N%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222021-12-03T22%3A25%3A53Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%224ZK9NVGT%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A1561563%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Schuwer%20et%20al.%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3ESchuwer%2C%20Robert%2C%20et%20al.%20%26%23x201C%3BWhat%20Is%20Open%20Pedagogy%3F%26%23x201D%3B%20%3Ci%3EYear%20of%20Open%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%2C%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.yearofopen.org%5C%2Fapril-open-perspective-what-is-open-pedagogy%5C%2F%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.yearofopen.org%5C%2Fapril-open-perspective-what-is-open-pedagogy%5C%2F%3C%5C%2Fa%3E.%20Accessed%202%20Dec.%202019.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22blogPost%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22What%20is%20Open%20Pedagogy%3F%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Robert%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Schuwer%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Maha%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Bali%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Arthur%20Gill%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Green%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Rajiv%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Jhangiani%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Heather%20M.%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Ross%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22Devon%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Ritter%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22blogTitle%22%3A%22Year%20of%20Open%22%2C%22date%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.yearofopen.org%5C%2Fapril-open-perspective-what-is-open-pedagogy%5C%2F%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en-US%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22QJKN5G4N%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222019-12-02T19%3A08%3A00Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22VW3GJU2Z%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A1561563%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Wiley%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222013-10-21%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3EWiley%2C%20David.%20%26%23x201C%3BWhat%20Is%20Open%20Pedagogy%3F%26%23x201D%3B%20%3Ci%3EIterating%20toward%20Openness%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%2C%2021%20Oct.%202013%2C%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fopencontent.org%5C%2Fblog%5C%2Farchives%5C%2F2975%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fopencontent.org%5C%2Fblog%5C%2Farchives%5C%2F2975%3C%5C%2Fa%3E.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22webpage%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22What%20is%20Open%20Pedagogy%3F%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22David%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Wiley%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22Hundreds%20of%20thousands%20of%20words%20have%20been%20written%20about%20open%20educational%20resources%2C%20but%20precious%20little%20has%20been%20written%20about%20how%20OER%20%5Cu2013%20or%20openness%20more%20generally%20%5Cu2013%20changes%20the%20practice%20of%20education.%20Substituting%20OER%20for%20expensive%20commercial%20resources%20definitely%20save%20money%20and%20increase%20access%20to%20core%20instructional%20materials.%20Increasing%20access%20to%20core%20instructional%20materials%20will%20necessarily%20make%20significant%20improvements%20in%20learning%20outcomes%20for%20students%20who%20otherwise%20wouldn%5Cu2019t%20have%20had%20access%20to%20the%20materials%20%28e.g.%2C%20couldn%5Cu2019t%20afford%20to%20purchase%20their%20textbooks%29.%20If%20the%20percentage%20of%20those%20students%20in%20a%20given%20population%20is%20large%20enough%2C%20their%20improvement%20in%20learning%20may%20even%20be%20detectable%20when%20comparing%20learning%20in%20the%20population%20before%20OER%20adoption%20with%20learning%20in%20the%20population%20after%20OER%20adoption.%20Saving%20significant%20amounts%20of%20money%20and%20doing%20no%20harm%20to%20learning%20outcomes%20%28or%20even%20slightly%20improving%20learning%20outcomes%29%20is%20clearly%20a%20win.%20However%2C%20there%20are%20much%20bigger%20victories%20to%20be%20won%20with%20openness.%22%2C%22date%22%3A%222013-10-21T21%3A41%3A27%2B00%3A00%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fopencontent.org%5C%2Fblog%5C%2Farchives%5C%2F2975%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en-US%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22QJKN5G4N%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222019-12-01T20%3A29%3A47Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22MPPE5NLG%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A1561563%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22creatorSummary%22%3A%22Wiley%20and%20Hilton%22%2C%22parsedDate%22%3A%222018%22%2C%22numChildren%22%3A2%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3EWiley%2C%20David%2C%20and%20John%20Hilton.%20%26%23x201C%3BView%20of%20Defining%20OER-Enabled%20Pedagogy.%26%23x201D%3B%20%3Ci%3EInternational%20Review%20of%20Research%20in%20Open%20and%20Distributed%20Learning%3C%5C%2Fi%3E%2C%20vol.%2019%2C%20no.%204%2C%202018%2C%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27http%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.irrodl.org%5C%2Findex.php%5C%2Firrodl%5C%2Farticle%5C%2Fview%5C%2F3601%5C%2F4724%27%3Ehttp%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.irrodl.org%5C%2Findex.php%5C%2Firrodl%5C%2Farticle%5C%2Fview%5C%2F3601%5C%2F4724%3C%5C%2Fa%3E.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22journalArticle%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22View%20of%20Defining%20OER-Enabled%20Pedagogy%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22David%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Wiley%22%7D%2C%7B%22creatorType%22%3A%22author%22%2C%22firstName%22%3A%22John%22%2C%22lastName%22%3A%22Hilton%22%7D%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22The%20term%20%5C%22open%20pedagogy%5C%22%20has%20been%20used%20in%20a%20variety%20of%20different%20ways%20over%20the%20past%20several%20decades.%20In%20recent%20years%2C%20its%20use%20has%20also%20become%20associated%20with%20Open%20Educational%20Resources%20%28OER%29.%20The%20wide%20range%20of%20competing%20definitions%20of%20open%20pedagogy%2C%20together%20with%20its%20semantic%20overlap%20with%20another%20underspecified%20term%2C%20open%20educational%20practices%2C%20makes%20it%20difficult%20to%20conduct%20research%20on%20the%20topic%20of%20open%20pedagogy.%20In%20making%20this%20claim%20we%20do%20not%20mean%20to%20cast%20doubt%20on%20the%20potential%20effectiveness%20of%20the%20many%20pedagogical%20approaches%20labeled%20open.%20In%20this%20article%2C%20rather%20than%20attempting%20to%20argue%20for%20a%20canonical%20definition%20of%20open%20pedagogy%2C%20we%20propose%20a%20new%20term%2C%20%5C%22OER-enabled%20pedagogy%2C%5C%22%20defined%20as%20the%20set%20of%20teaching%20and%20learning%20practices%20that%20are%20only%20possible%20or%20practical%20in%20the%20context%20of%20the%205R%20permissions%20that%20are%20characteristic%20of%20OER.%20We%20propose%20criteria%20used%20to%20evaluate%20whether%20a%20form%20of%20teaching%20constitutes%20OER-enabled%20pedagogy%20and%20analyze%20several%20examples%20of%20OER-enabled%20pedagogy%20with%20these%20criteria.%22%2C%22date%22%3A%2210%5C%2F2018%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22en%22%2C%22DOI%22%3A%22%22%2C%22ISSN%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22http%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.irrodl.org%5C%2Findex.php%5C%2Firrodl%5C%2Farticle%5C%2Fview%5C%2F3601%5C%2F4724%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22QJKN5G4N%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222019-12-01T20%3A29%3A47Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22SM4BLK7P%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A1561563%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3E%3Ci%3EOSCQR%3C%5C%2Fi%3E.%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Foscqr.org%5C%2F%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Foscqr.org%5C%2F%3C%5C%2Fa%3E.%20Accessed%2025%20Nov.%202019.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22webpage%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22OSCQR%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Foscqr.org%5C%2F%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22QJKN5G4N%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222019-12-01T20%3A29%3A47Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%22IWXHMML3%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A1561563%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3E%3Ci%3EQM%20Rubrics%20%26amp%3B%20Standards%20%7C%20Quality%20Matters%3C%5C%2Fi%3E.%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.qualitymatters.org%5C%2Fqa-resources%5C%2Frubric-standards%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.qualitymatters.org%5C%2Fqa-resources%5C%2Frubric-standards%3C%5C%2Fa%3E.%20Accessed%2025%20Nov.%202019.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22webpage%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22QM%20Rubrics%20%26%20Standards%20%7C%20Quality%20Matters%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22%22%2C%22date%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.qualitymatters.org%5C%2Fqa-resources%5C%2Frubric-standards%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22QJKN5G4N%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222019-12-01T20%3A29%3A47Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%228WU5QYLA%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A1561563%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3E%3Ci%3ECape%20Town%20Open%20Education%20Declaration%2010th%20Anniversary%3C%5C%2Fi%3E.%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.capetowndeclaration.org%5C%2Fcpt10%5C%2F%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.capetowndeclaration.org%5C%2Fcpt10%5C%2F%3C%5C%2Fa%3E.%20Accessed%201%20Dec.%202019.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22webpage%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22Cape%20Town%20Open%20Education%20Declaration%2010th%20Anniversary%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22The%20Cape%20Town%20Open%20Education%20Declaration%20was%20published%20on%20January%2022%2C%202008%2C%20sparking%20a%20global%20call%20to%20action%20that%20has%20grown%20into%20the%20vibrant%20open%20education%20movement%20that%20exists%20today.%20In%20honor%20of%20the%20ten%20year%20anniversary%2C%20we%20took%20a%20look%20back%20at%20the%20last%20decade%20and%20identified%20ten%20key%20directions%20to%20move%20open%20education%20forward.%20Click%20on%20the%20cards%20below%20to%20read%20more%20about%20each%20topic%2C%20or%20consider%20suggesting%20your%20own.%22%2C%22date%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.capetowndeclaration.org%5C%2Fcpt10%5C%2F%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22English%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22QJKN5G4N%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222019-12-01T20%3A35%3A00Z%22%7D%7D%2C%7B%22key%22%3A%222QXQC3BG%22%2C%22library%22%3A%7B%22id%22%3A1561563%7D%2C%22meta%22%3A%7B%22numChildren%22%3A1%7D%2C%22bib%22%3A%22%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-bib-body%5C%22%20style%3D%5C%22line-height%3A%202%3B%20padding-left%3A%201em%3B%20text-indent%3A-1em%3B%5C%22%3E%5Cn%20%20%3Cdiv%20class%3D%5C%22csl-entry%5C%22%3E%3Ci%3EThe%20Cape%20Town%20Open%20Education%20Declaration%3C%5C%2Fi%3E.%20%3Ca%20href%3D%27https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.capetowndeclaration.org%5C%2Fread-the-declaration%27%3Ehttps%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.capetowndeclaration.org%5C%2Fread-the-declaration%3C%5C%2Fa%3E.%20Accessed%201%20Dec.%202019.%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%5Cn%3C%5C%2Fdiv%3E%22%2C%22data%22%3A%7B%22itemType%22%3A%22webpage%22%2C%22title%22%3A%22The%20Cape%20Town%20Open%20Education%20Declaration%22%2C%22creators%22%3A%5B%5D%2C%22abstractNote%22%3A%22The%20Cape%20Town%20Open%20Education%20Declaration%20arises%20from%20a%20small%20but%20lively%20meeting%20convened%20in%20Cape%20Town%20in%20September%202007.%20The%20aim%20of%20this%20meeting%20was%20to%20accelerate%20efforts%20to%20promote%20open%20resources%2C%20technology%20and%20teaching%20practices%20in%20education.%20Convened%20by%20the%20Open%20Society%20Institute%20and%20the%20Shuttleworth%20Foundation%2C%20the%20meeting%20gathered%20participants%20with%20many%20points%20of%20view%20from%20many%20nations.%20This%20group%20discussed%20ways%20to%20broaden%20and%20deepen%20their%20open%20education%20efforts%20by%20working%20together.%20The%20first%20concrete%20outcome%20of%20this%20meeting%20is%20the%20Cape%20Town%20Open%20Education%20Declaration.%20It%20is%20at%20once%20a%20statement%20of%20principle%2C%20a%20statement%20of%20strategy%20and%20a%20statement%20of%20commitment.%20It%20is%20meant%20to%20spark%20dialogue%2C%20to%20inspire%20action%20and%20to%20help%20the%20open%20education%20movement%20grow.%22%2C%22date%22%3A%22%22%2C%22url%22%3A%22https%3A%5C%2F%5C%2Fwww.capetowndeclaration.org%5C%2Fread-the-declaration%22%2C%22language%22%3A%22English%22%2C%22collections%22%3A%5B%22QJKN5G4N%22%5D%2C%22dateModified%22%3A%222019-12-01T20%3A37%3A05Z%22%7D%7D%5D%7D

Bali, Maha. “Curation of Posts on Open Pedagogy #YearOfOpen.”

Reflecting Allowed, 21 Apr. 2017,

https://blog.mahabali.me/whyopen/curation-of-posts-on-open-pedagogy-yearofopen/.

Bali, Maha. “What Is Open Pedagogy? #YearOfOpen Hangout April 24.”

Reflecting Allowed, 20 Apr. 2017,

https://blog.mahabali.me/whyopen/what-is-open-pedagogy-yearofopen-hangout-april-24/.

Baroud, Fawzi, et al. “What Is Open Education?”

Year of Open,

https://www.yearofopen.org/what-is-open-education/. Accessed 2 Dec. 2019.

Cronin, Catherine. “Openness and Praxis: Exploring the Use of Open Educational Practices in Higher Education.”

The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, vol. 18, no. 5, Aug. 2017,

http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/3096.

DeRosa, Robin. “Open Pedagogy: Quick Reflection for #YearOfOpen.”

Actualham, 24 Apr. 2017,

http://robinderosa.net/uncategorized/1775/.

DeRosa, Robin, and Rajiv Jhangiani. “Open Pedagogy Notebook.”

Open Pedagogy Notebook, 16 Mar. 2018,

http://openpedagogy.org/open-pedagogy/.

Hodgkinson-Williams, Cheryl Ann, and Henry Trotter. “A Social Justice Framework for Understanding Open Educational Resources and Practices in the Global South.”

Journal of Learning for Development - JL4D, vol. 5, no. 3, Nov. 2018,

http://jl4d.org/index.php/ejl4d/article/view/312.

Inamorato dos Santos, Andreia, et al.

Opening up Education: A Support Framework for Higher Education Institutions. Text, Publications Office of the European Union, 27 July 2016, p. 78,

https://ec.europa.eu/jrc/en/publication/eur-scientific-and-technical-research-reports/opening-education-support-framework-higher-education-institutions.

Lambert, Sarah Roslyn. “Changing Our (Dis)Course: A Distinctive Social Justice Aligned Definition of Open Education.”

Journal of Learning for Development - JL4D, vol. 5, no. 3, Nov. 2018,

https://jl4d.org/index.php/ejl4d/article/view/290.

McVerry, Greg. “Draft Framework for Effective Teaching and Higher Ed.”

INTERTEXTrEVOLUTION, 1 Nov. 2019,

https://jgregorymcverry.com/frameworkforeffectivehighered.

Online Learning Consortium. “OLC Quality Scorecard: Improve the Quality of Online Learning & Teaching.”

Online Learning Consortium,

https://onlinelearningconsortium.org/consult/olc-quality-scorecard-blended-learning-programs/. Accessed 25 Nov. 2019.

Schuwer, Robert, et al. “What Is Open Pedagogy?”

Year of Open,

https://www.yearofopen.org/april-open-perspective-what-is-open-pedagogy/. Accessed 2 Dec. 2019.

Wiley, David. “What Is Open Pedagogy?”

Iterating toward Openness, 21 Oct. 2013,

https://opencontent.org/blog/archives/2975.

Wiley, David, and John Hilton. “View of Defining OER-Enabled Pedagogy.”

International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, vol. 19, no. 4, 2018,

http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/3601/4724.

OSCQR.

https://oscqr.org/. Accessed 25 Nov. 2019.

QM Rubrics & Standards | Quality Matters.

https://www.qualitymatters.org/qa-resources/rubric-standards. Accessed 25 Nov. 2019.

Cape Town Open Education Declaration 10th Anniversary.

https://www.capetowndeclaration.org/cpt10/. Accessed 1 Dec. 2019.

The Cape Town Open Education Declaration.

https://www.capetowndeclaration.org/read-the-declaration. Accessed 1 Dec. 2019.

Bibliography Contributors