Paul A. Kirschner & Mirjam Neelen

It’s a common theme on social media: The perceived need of a radical change in education. One of the suggested radical changes is to focus less on instruction and more on play and discovery.

Recently, we saw a Tweet where Tweeter 1 (who is a proponent of more play and less instruction) asked Tweeter 2 who challenged the view that play equals learning: “Do you have children yourself”? Apart from the fact that this is an impertinent question, the reason why Tweeter 1 asked it was to imply that, if you look at how your own children learn, you would simply understand that this is how they learn best.

This is exactly the type of reasoning that proponents of the idea that education needs to focus more on play and less on ‘instruction’ follow. They point to the fact that children learn how to speak their native language in a playful, natural way, that they play together and discover new things while playing, that they’re constantly solving problems and exploring the world, just through experimentation. They figure out stuff as they go.

Therefore, so argue the ‘play-to-learn proponents’, it makes total sense to approach learning how to learn other things, such as reading, writing, doing maths, etcetera in the same way. Children are living proof that this learning through play and discovery is the best way to learn.

At first glance, this sounds reasonable. We all know that it’s true that children learn a lot through play, discovery, experimentation, and simply through interacting with the world and people around them.

However, there’s a catch. There’s a fundamental difference between the way children learn to speak their mother tongue, communicate with others around them, and collaborate during play and how they learn to read, write, and do maths.

Learning through an evolutionary lens

A brief note

There’s a lot of debate going on when looking at learning through an evolutionary lens. In brief, there’s controversy when it comes to the question what type of education is best. What the ‘best way’ is, depends on the lens through which the researcher looks (for example, anthropology, archaeology, zoology, or cognitive psychology). There’s also a distinction between instructional practice and the other important day-to-day responsibilities that a teacher has in the classroom, such as creating a safe and optimal learning environment and monitoring learner progress (Berch, 2017). The report ‘Education Through an Evolutionary Lens’ sheds some light on the overall discussion.

In this blog, we look through David Geary’s evolutionary lens as this helps understand why children prefer to play, discover and experiment, why they learn certain things best this way, and why they need other approaches to learning when it comes to ‘school stuff’, such as reading, writing, or doing maths.

David Geary distinguishes between biologically primary and biologically secondary learning (also called evolutionary primary and evolutionary secondary learning – You can read an earlier blog on this topic here). The first takes place as part of evolution, the second as part of cultural development. Schools, so states Geary (2017) “… are the interface between culture and evolution” (p 16).

What’s the difference?

Biologically Primary Learning: Survival!

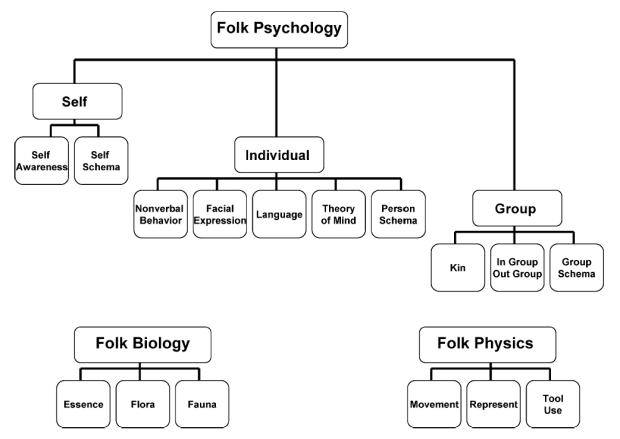

According to Geary, as soon as we’re born, we consciously focus our attention on 1) ourselves and other (groups of) people (folk psychology), 2) other living organisms around us, such as animals and plants (folk biology), and 3) our living environment and the ‘tools’ that we use in this environment (folk physics).

From an evolutionary perspective, we do this because the availability of social and natural resources influences – or actually, determines – our chances of survival. We need to recognise and communicate with our parents in order be nurtured and protected, be able to work with others, to know and recognise who is a member of our ‘in-group’ (and hence, who is safe) who belongs to the ‘out-group’ and is therefore a possible enemy. We also need to know which plants are safe and which are poisonous, which animals are harmless, and which are dangerous. And we need to navigate in our environment and learn things like how to use a stick and what for… all these are examples of ‘life or death’ knowledge. It’s the type of knowledge that determines if you’re going to survive and procreate or if you’re going to die. After all, if you weren’t able to do or know all this, you were literally doomed. This biologically primary knowledge has evolved (literally; not figuratively) through experience. We can directly store it in our long-term memory, without conscious processing in our working memory. Thank goodness!

However, when our societies became more complex, we needed more than ‘just’ primary knowledge. In addition to surviving physically, humans had to acquire other types of knowledge to be able to valuably participate in and contribute to society. This is called cultural knowledge (this needs to be interpreted in a broad sense and as the antipode of primary knowledge, which we then convey to the next generation) and is a relatively recent development in our evolutionary history as homo sapiens[1]. Reading and writing are examples of fairly recent cultural knowledge; it’s important in many societies but we can survive as a species and as a member of that species without it. As such, we have not developed primary mechanisms to gain this knowledge and probably never will. Thanks to these types of skills we are no longer dependent on information that’s available to us in our direct environment and ‘in the moment’. Instead, we have access to more abstract knowledge through information resources such as books and the Internet. We can keep this knowledge, update it where needed, and make it available to lots of people.

This is the type of knowledge we teach in schools: cultural or biologically secondary knowledge. As stated above, this type of knowledge is fairly recent (from an evolutionary perspective, that is; writing is only about 6000 years old; a small ripple in our long evolutionary history!). Secondary biological knowledge is necessary to have equal opportunities and to participate in society, but it isn’t (again from an evolutionary perspective) required to survive.

Evolution doesn’t only play a role in what we want to learn but also how we prefer to learn. Geary’s theory helps us to understand why children are naturally motivated to learn through play, experimentation, and discovery, and that they might not be so naturally motivated to learn how to read, write, spell, or do maths in a different way.

Suppressing natural preferences

In everyday situations we lean on things like heuristics, rules of thumb, and mnemonics. This is how we quickly and automatically make sense of the world around us and impart meaning. When we meet someone, we usually know right away if that person is a male or a female and you can infer their mood based on their facial expression.

These, now automatic, cognitive processes help us to ensure that our interactions with others are (usually) successful. We have acquired these processes through observation, discovery, and play. It’s a type of unconscious, serendipitous learning.

It would be wonderful if we could acquire biologically secondary knowledge with the same ease, but unfortunately that’s not so. For example, skills such as reading, spelling, writing, doing maths, etcetera, take conscious effort and involve the limits of our working memory.

When you understand the difference between biologically primary and secondary learning, as explained by Geary, you’ll understand why we, as humans, are motivated to learn certain things and why we learn certain things easily (biologically primary learning) and why other things take more conscious effort and might not so much appeal to us at first (biologically secondary learning).

Or, as Principe (2017) states: “An appreciation of [the] deep history of our brains makes it clear that the classroom and many of the skills that we teach in school, like reading, writing, and most of modern-day mathematics, are foreign elements in the natural ecology of children” (p 4).

Geary (2017) explains that “For many children, the motivation to learn these skills will require social and cultural supports (e.g., highlighting accomplishments of engineers) and encouragement (e.g., focus on the payoffs to effort and hard work). Evolutionarily novel learning requires, to some extent, disengagement from natural ways of learning (e.g., play)” (p 16).

What does this mean for teaching and learning in schools?

What all of this means for teaching and learning

For starters, although we can’t just assume that all learners have a solid foundation of biologically primary knowledge and skills (e.g., children with special needs might have a different of incomplete foundation), most learners would have picked up biologically primary knowledge and skills as part of ‘normal’ development.

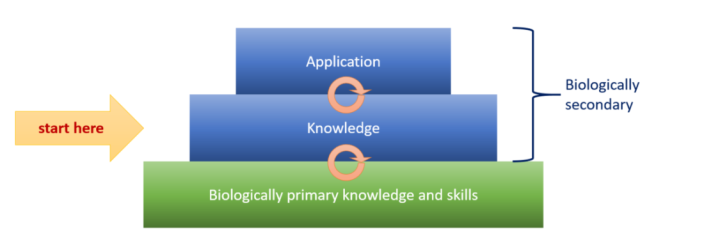

The current evidence we have suggests that, when we learn biologically secondary knowledge (e.g., doing maths), we start with applications of knowledge (application and knowledge go hand in hand) and we fall back on our biologically primary knowledge and skills, for example means-end analysis or trial-and-error when we have knowledge gaps and we need to figure it out (see Ashman’s taxonomy).

Ashman’s Taxonomy (Using Ashman’s Taxonomy)

Gray (2011) argues that children are perfectly capable of learning in a self-directed manner and that this type of learning is sufficient to acquire even complex abstract knowledge. Of course, it’s not necessarily true that we won’t be able to learn anything ‘secondary’ through play or discovery (for example, some children learn how to read before they go to school. Mirjam was one of them. She was able to read before she went to school). First of all, it’s important to realise the NO ONE learns how to read magically. Most likely, those who learn how to read before they go to school have parents / grandparents / caretakers / an older sibling who read loads of books to them, , helped them to recognise letters and how they sound, played games to encourage phonemic awareness (e.g., synthesis of the sounds of single letters into syllables and syllables into words, rhyming, etc). In other words, those who learn how to read before going to school, likely have learned through playful instruction and not through play.

In addition, we need to ask ourselves, first, how efficient that approach is, second, do we really want to leave it to chance or do we want to provide each child with equal opportunities, and last, what level of proficiency would a child achieve without explicit instruction and guidance from an expert (the teacher)?

When you look at it from that perspective, explicit instruction, starting with knowledge building is the most efficient and inclusive way to acquire biologically secondary knowledge. Through explicit instruction, we can teach children to apply domain-specific knowledge and teach them domain-specific problem-solving strategies so that over time, they can become effective and efficient problem-solvers in such a domain, building expertise in a given area (Sweller, 2017).

As an instructor, take learners by the hand and motivate them to learn in various ways, including ways that go against their instincts or ways they might struggle with at first. This doesn’t mean you should ditch the play; rather it means to make informed decisions on when to play and when not to play in order to play it safe when it comes to our children’s education.

And if you still think that discovery through play the best way is for children to learn, then let you child or grandchild learn to navigate a busy intersection by playfully discovering how to do it, instead of via explicit instruction (Thanks Tim Surma (@timsurma on Twitter) for this great example).

References

Ashman, G. (2019, September 12). Using Ashman’s Taxonomy [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://gregashman.wordpress.com/2019/09/12/using-ashmans-taxonomy/

Berch, D.B. (2017). Evolutionary Theory Can Inform the Intelligent Design of Educational Policy and Practice. In Education Through an Evolutionary Lens. Retrieved from https://evolution-institute.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/edu-publication-web.pdf

Geary, D. C. (2008). An evolutionarily informed education science. Educational Psychologist, 43(4), 179-195. Retrieved from https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/e8bf/72d729dfd059fee7cf8b8a1a7bd84c760404.pdf?_ga=2.36070311.628041588.1546724191-1077163452.1546724191

Geary, D. C. (2017). The Evolved Mind in the Modern School. In Education Through an Evolutionary Lens. Retrieved from https://evolution-institute.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/edu-publication-web.pdf

Gray, P. (2011). The evolutionary biology of education: How our hunter-gatherer educative instincts could form the basis for education today. Evolution: Education and Outreach, 4, 28-40.

Principe, G. (2017). Introduction: Education through an Evolutionary Lens. In Education Through an Evolutionary Lens. Retrieved from https://evolution-institute.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/edu-publication-web.pdf

Sweller, J. (2017). Evolutionary Educational Psychology as a Base for Instructional Design. In Education Through an Evolutionary Lens. Retrieved from https://evolution-institute.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/edu-publication-web.pdf

[1] The invention of the first writing systems is roughly contemporary with the beginning of the Bronze Age of the late 4th millennium BC. Conventional history assumes that the writing process first evolved from economic necessity in the ancient Near East. Writing most likely began as a consequence of political expansion in ancient cultures, which needed reliable means for transmitting information, maintaining financial accounts, keeping historical records, and similar activities. Around the 4th millennium BC, the complexity of trade and administration outgrew the power of memory, and writing became a more dependable method of recording and presenting transactions in a permanent form. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Writing#History

Reblogged this on kadir kozan.

LikeLike

Prof Kirschner continues his crusade for learning by direct instruction. This is OK.

However, what he claims about play and learning in this article/blog is gratuitious nonsense as he doesn’t even define play nor learning. In the last paragraph of this contribution he seems to be delighted about an example that definitely may disqualify play as a way of teaching children complex (secondary knowledge and skills). It only shows that he is confusing play and trial and error. This kind of theory- poor cliams about play doesn’t bring us much further ahead.

LikeLike

Professor Van Oers / Collega,

First off, a reply that begins with ‘his crusade for…’ is what’s known as an ad hominem argument and I didn’t expect that from you. Having said that, though I have the feeling that this reply will probably only lead to a reply to a reply, I’ve decided to do it anyway in an attempt to clear some things up.

Direct instruction neither prohibits nor discourages play nor playful instruction. The two aren’t mutually exclusive. What it does is stipulate that effective learning is predicated on good instruction even, and possibly especially for young children in a warm and playful setting. When one teaches a child through play, it’s done in a supervised/controlled way. The emphasis here is on supervision/control (support + guidance = instruction). This is true for learning how to cross a street or learning how to read or do maths. Play is a pedagogical approach that supports the instruction (NL: didactiek) and isn’t in conflict with it.

Of course one can learn in an incidental way through play alone (see definition below), but this is often neither effective nor efficient (I can hear the moaning already) in that it often takes quite a large amount of time and also very often leads to stubborn misconceptions which are difficult to correct if it isn’t properly supported and guided (again control/supervision).

As for definitions:

Learning: A more or less stable, long-lasting change in one’s long-term memory

Playing: Engaging in an activity for enjoyment and recreation rather than a serious or practical purpose.

When it comes to learning, and especially for young children, instruction without play can be boring but play without instruction is futile.

Respectfully,

paul

LikeLike