Editor’s Note: the following is a guest post by Simon Wakeling, Stephen Pinfield and Peter Willett. Simon is a Lecturer in the School of Information Studies at Charles Sturt University, and Stephen and Peter are Professors at the University of Sheffield’s Information School (where Simon was also based, until his move to CSU). In collaboration with colleagues at Loughborough University they recently completed a large scale AHRC funded research project investigating open-access mega-journals.

The internet is awash with commentary. Those of us who read news services, or watch YouTube videos, or indeed engage with any form of content published online, know that scrolling down will likely reveal comments left by other consumers of that same content — sometimes only a handful, but often hundreds or even thousands. This phenomenon is the subject of much debate, particularly concerning the tone of discourse and the dangers of its manipulation. One thing that is palpably not in question is the level of commenting online.

Ask scholarly publishers about the rates of commenting on the articles they publish, however, and a very different picture emerges. Commenting functionality, which allows readers of an online article to add a comment relating to that article, visible to future readers, has been a feature of online academic publishing since its earliest days. While comparisons with the massive volume of comments on popular news and media sharing sites are obviously imperfect, there is nonetheless a widespread perception that article commenting has failed to embed itself in academic culture.

Why is this significant? Article commenting is most relevant to two related aspects of today’s scholarly publishing environment. The first is the concept of post-publication peer review (PPPR). In her Scholarly Kitchen blog on commenting in 2017, Angela Cochran argued that “post-publication peer review = online commenting”. While this might not necessarily be true for every version of PPPR (F1000 Research’s process, for example, involves invited reviewers submitting an open review after initial publication of the manuscript), it is true that some proponents of PPPR envision a model wherein the community of readers provide ongoing evaluation of the scholarly literature through comments.

This notion of a community reviewing and evaluating articles is of particular importance to open-access mega-journals (OAMJs). Such journals operate soundness-only review policies which explicitly exclude judgements of significance, novelty and interest from the decision to publish, instead accepting any work that is deemed scientifically sound. The intention, as PeerJ’s Publisher and Co-founder Peter Binfield put it, is to “let the community decide”. He explained:

“If subjective filtering (on whatever criteria) has not happened ‘pre-publication’ … then clearly the community needs to apply new tools ‘post publication’ to try to provide these types of signals based on the reception of the article in the real world” (Binfield, 2013)

In practice, these “new tools” have primarily been post-publication metrics, particularly altmetrics, and article commenting. Indeed the PLOS ONE website explicitly states that its comment functionality is intended to “facilitate community evaluation and discourse around published articles”.

Despite the near consensus about the popularity (or lack thereof) of commenting on academic articles, there is surprisingly little publicly available data relating to commenting rates. We could find only two blog posts by Euan Adie, in 2008 and 2009, that examined commenting rates and the nature of comments left on articles published by BioMed Central (BMC) and PLOS ONE. He determined that only a small proportion of papers had received comments (18% of PLOS ONE articles, and just 2% of BMC articles).

To address this, as part of a team of academics from the Universities of Sheffield and Loughborough, we have recently published research into article commenting on PLOS journals. This work is based on a data set generously provided by PLOS, comprising all comments (and their supporting metadata) left on PLOS articles between 2003 (the date of the first PLOS article) and the end of 2016.

What did we find?

1. Commenting rates are low, and getting lower

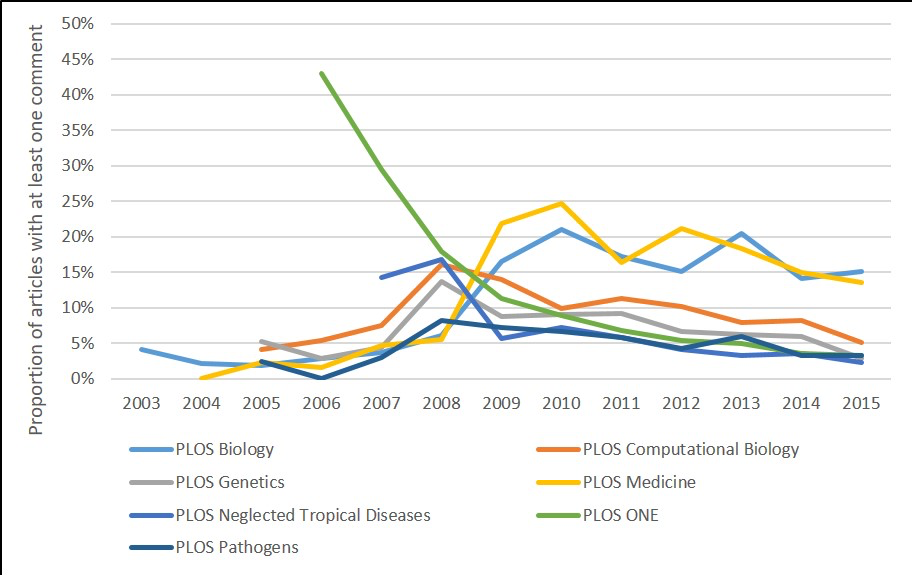

Our analysis showed that since 2003, only 7.4% of articles published across all PLOS journals have been commented upon — and when comments left by publisher operated accounts are excluded, this figure drops to 5.2%. We also found that commenting rates have been declining for all journals since 2010.

2. Very few articles have multiple comments

Articles that had been commented on received on average 1.9 comments, with two thirds of these articles receiving a single comment. Just 592 articles were found to have five or more comments, that figure representing 0.3% of all published articles. The articles with the most comments were mostly found to have been the center of some controversy. The (now retracted) article with the most comments (206) refers to “the Creator”, while the apparent stimuli for comments on other articles include the alleged refusal of researchers to share underlying data, results that contradict other influential papers, and apparently serious perceived flaws in research methodology and analysis. The article with the eighth highest number of comments (46) has no reader comments whatsoever; all comments are made by the author, and correct the order of references in the article.

3. Most (but not all) comments discuss the academic content of the paper.

As part of our research we developed a typology of comments, and manually coded a 10% sample of the PLOS data set (2,888 comments in total). Within this typology the 11 categories were organized into two distinct groups. Firstly, there are procedural comments: those identifying spelling or typographical errors, noting media coverage, linking to supplementary data etc. Secondly, there are academic comments: those praising or criticizing the paper, asking questions of the authors, linking to related material, or generally discussing the intellectual content of the paper. It is this second type of comment that relates to the concept of PPPR. We found that around a third of comments were procedural, and two thirds academic, with discussion of the content of the paper the most common (52% of all comments in the sample).

4. More comments address issues of scientific soundness than the significance of the work

We further analyzed comments coded as academic discussion, to determine whether they addressed any of the typical aspects of peer review (novelty, relevance to the journal, significance, and technical soundness). Two thirds of academic discussion comments left on PLOS ONE articles were found to cover the scientific soundness of the work, but just 13.6% its significance.

5. There is variation in commenting across journals

While most of the findings presented above are based on the aggregated data set, it was striking that different PLOS journals exhibited quite different commenting characteristics. PLOS Biology and PLOS Medicine in particular were found to have higher rates of commenting since 2009, and that those comments were more likely than for other journals to be academic in nature, and to discuss the significance of the findings.

What do these results mean?

In part, our research confirms what many publishers already know: academics rarely comment on articles. There has been much speculation (but little formal research) into why this should be the case. It could be, as Neylon and Xu suggest, that we are simply observing the 90-9-1 rule in action (90% of people observe, 9% make small contributions, and 1% are responsible for most of the content) — although that is more an observation of a pattern of behavior rather than an explanation as such. It may be that academics in general, particularly those at early stages of their careers, are uncomfortable publicly engaging in critical discussion of other people’s work. An unwillingness to comment might also stem from the long standing culture of academics, as Cochran suggests, where discussion of articles takes place in well-understood environments — staff rooms (usually accompanied by coffee), in research group meetings, or at conferences.

Cochran also notes that “what’s missing from commenting sites specifically on mega-journals, database sites, and third party sites is community.” We think our results offer some support for this view, most notably in the fact that PLOS Medicine and PLOS Biology — the longest established and highest ranked of the PLOS journals, and those that might best be said to have a community of readers — both exhibit significantly more commenting activity than the much larger and topically diverse PLOS ONE.

Understandings of what constitutes peer review are also clearly very embedded in academic communities and difficult to challenge. Some of our other work on mega-journals has led us to question not so much the model of soundness-only peer-review (which in fact involves pre-publication soundness-only peer review followed by post-publication quality indicators of novelty, significance and relevance), but ways in which it can be incorporated into scholarly practice in the short term. This challenges many deep-seated presumptions about peer review, such as when it should happen (the assumption is pre-publication) and what it should include (novelty, significance, and interest as well as rigor and soundness). It can take time for new models to become accepted.

For PPPR and OAMJ models to work as originally conceived publishers not only need to persuade more academics to comment more frequently — a serious enough challenge on its own — but also to engage in a different type of commenting.

Our most significant finding, however, relates to the analysis of what comments are typically about. For commenting to properly constitute PPPR, or communicate a community’s views of a mega-journal article, a sufficient number of comments arguably need to address the types of issues typically considered in peer review reports (novelty, significance, and interest). Our research shows that while academic discussion of the article is relatively prevalent, for PLOS ONE articles these comments are most likely to address issues of technical soundness — ironically, the one factor already addressed in peer review. So for PPPR and OAMJ models to work as originally conceived publishers not only need to persuade more academics to comment more frequently — a serious enough challenge on its own — but also to engage in a different type of commenting. Much of this is about academic cultures, of course, which are notoriously difficult to shift, at least with current incentives. Contributing to community dialogue in ways such as commenting, as well as engaging in peer review more generally, needs greater recognition.

Discussion

22 Thoughts on "Guest Post – A Study of Commenting on PLOS Articles"

Thank you Simon, Stephen and Peter for an interesting article.

Tempting as it is to remain one of the 90%, I believe that I should comment.

I suspect that there are a multiplicity of reasons why there is a reluctance to comment. Not least the perceived ‘rules’ of commenting (and the opacity of these rules, as you suggest), the lack of an established community of practice in the PLOS ecosystem and also potential for less experienced academics to be criticised if they do comment.

A supportive environment for balanced discourse is not always in place and if people do not feel welcome to comment, they are likely to remain outside academic debate, unless they are in the confines of their own department or speciality.

Creating such an environment as you also imply is not in anyway straightforward. The scholarly kitchen is certainly a good place to start.

One makes a comment on the assumption that it will be read. The more readers the better. A major group of readers are those who are reviewing grant applications, books and papers. Here there are lists of references, some of which a reviewer may not be familiar with. Rather than go directly to an actual paper, a busy reviewer wants a quick look at the abstract, which is a click away in PubMed. Having inspected the abstract, he/she can then usually click at top-right to access the paper if desired. More importantly, until 2018 he/she could first click on PubMed Commons (PMC) to check for comments from credited reviewers (not just anyone as in PubPeer).

Over the five year period of its existence, over 7000 comments were made at PMC. Speaking for myself, I made comments at PMC because I thought they would be read, not only by the authors but also, because of easy access, by the many who undertook the laborious task of reviewing. I suspect others were similarly motivated.

As a solution to the declining commenting problem, I suggest that PLOS and other publishers automatically link the comments they receive to PMC. However, first they must lobby the NCBI to reopen this most valuable resource.

This work is very helpful in evaluating whether online commenting (aka PPPR) can truly function as its proponents envision or advocate. At least for one megajournal, the answer is clearly “no.”

PLOS provided the researchers with commenting data from 2003 through 2016. It does make me wonder whether declining participating rates have continued. I also wonder why the above figure only includes data through 2015?

With regard to the figure only extending to 2015, this is because the data were generated by PLOS at the start of 2017. This meant that articles published at the end of 2016 had not had much time to accrue comments. While our study also established that most comments are left relatively soon after publication (51.4% within 4 weeks, 86.5% within a year), there is still a significant lag in comment numbers. So we didn’t think it appropriate to include 2016 numbers in the figure.

Just wanted to pop in to say that I particularly enjoyed this article and it gave me much food for thought. I personally support the idea that sound science should be published before considering novelty or significance because we all know negative results don’t get published but can be so, so useful (especially to deter others from duplicating the same work.)

I hope this is a trend we continue to see, despite it being an uphill battle.

But you don’t have to choose. You could have carefully reviewed material that judges on originality and still have an ecosystem of papers with less recognizable significance. The first works by subscription, the second by APCs. Why everyone insists on a single way to do things is a mystery to me.

Wouldn’t authors/institutions be less likely to pay an APC for a less significant work?

Also, if Gold Open Access requiring APCs become the location of less significant works, then I could see even fewer authors wanting to publish in Gold Open Access journals, since it would start being seen as less important on their CVs.

It already is less important on their CVs. No change there. APCs could be a fraction of what they are now if one dispensed with the extensive editorial review of the established publications. No reason for one size to fit all. No reason for puristic thinking. It’s a sloppy world, thank god.

APCs could be a fraction of what they are now if one dispensed with the extensive editorial review of the established publications.

And, of course, there’s a segment of the scholarly-publishing marketplace in which this is exactly the model that prevails: the predatory journals market. Predatory journals typically charge much lower APCs than legitimate journals do, and are able to do so for precisely this reason.

Thanks for this article, as already implied journals relying on on-line commenting for review do not work and hence are no more than the equivalent of preprints. This data confirms the importance of peer review either before or after publication to ensure the maintenance of quality in the scientific record.

I think that the problem that these post-publication importance assessments will always have is that they will never be able to compete with that most established importance indicator, the citation. If I cite a work I not only have read it and gotten an opinion, but also found something in it relevant enough to warrant basing some bit of my own work thereon. This is a much more stringent criterion for relevance, so once there are citations, why should I ever be interested in someones quick and dirty opinion in a comment field?

I also think that there is faulty thinking in the idea that commenting on scientific articles could ever generate response rates similar to those found in big news outlets (or the Scholarly Kitchen!). Articles that generate a lot of comments in a regular news outlet are opinions written to generate other opinions. The purpose of a scientific article is to dispassionately disseminate facts. When I look at the diagrams here I see an artificially high initial interest that is slowly moving towards a level that seems more reasonable. In fact, it points to the basic soundness of what we do that we do not follow the rules of the opinion factories.

A problem is also that no-one in their right mind would want to read such comments. If I am indeed an expert in my field, why should I waste time reading what other people thought about it before forming my own opinion? And once I have my own opinion, why should I waste time reading those of other people? Either it was not interesting, in which case I (at most) briefly regret the time it took to read it and then move on, or it was interesting, in which case I use it to do science. I see no place for online comments in this equation.

It seems to me that if the reader knows beforehand that the article is not novel, significant or relevant basically what one is looking at is another method that may or may not be applicable to the research at hand. If it is of use one could comment by saying thanks for the method. But, if not one could say: Oh, I know that and why would I comment on it! Commenting takes time and time is precious.

To be fair, I am sure there are plenty of papers in PLOS ONE that are novel, significant, and relevant. It’s just that these are not criteria for acceptance.

Thank you so much for sharing your results here. I am glad to have more data on this topic and that you were able to confirm some of my hunches based on limited data earlier.

I will continue to be concerned that the folks who think papers should just go online and the community will peer review it later have grossly overestimated the desire of researchers to participate in this activity. Without the structure of an editor formally inviting an individual to critically read and review submitted papers, it won’t happen.

Thanks for the summary here (also worth reading the full article, which is sadly not OA!).

Post-publication commenting and review have always been a key element of PLOS’s vision and were an integral part of the original plan for PLOS ONE. As our own analysis and this research demonstrate, they haven’t taken off at PLOS so far (any more than they have at other publishers who have tried similar things, including Nature Communication and Scientific Reports).

This kind of analysis is really helpful in understanding why various forms of commentary have largely failed. Our own view is that there are three key reasons: the concept was one that the community wasn’t ready for; post-publication is likely at the wrong stage of the article lifecycle for commenting; and, as Angela has noted, the sense of community hadn’t been established. But I’m not sure that means that we should abandon community comments/review altogether.

Emerging preprint ecosystems are starting to change the opportunities for and attitudes towards commenting as part of a wider push for greater openness and transparency in peer review. After we roll out published peer review reports at PLOS this month, we’ll be moving on to pilots with preprint commenting to assess the ways in which these may complement more traditional peer review (for example, looking at how we can feed comments on bioRxiv preprints to the action editor for optional consideration alongside more formal review). There are clearly many issues to be worked through – comment format, concerns about open identity, incentives and credits, etc. But preprints seem like an exciting place to experiment for the very reason Donald notes above – they are far more likely to be read and to be of value at this point in the article’s development.

I have thought that researchers don’t comment often on published articles because 1) they really don’t have time to do even a light review of the work and 2) they don’t want to introduce points of contention that they themselves may publish after their own further research.

Finding reviewers for scientific manuscripts is not an easy task, particularly with so much pressure on researchers nowadays to publish (and so many outlets for them to do so). Finding researchers to provide salient points about a published paper (points worthy of an actual reviewer) and then even to follow up as part of a larger discourse on the paper is increasingly difficult to accomplish.

Great study, but be careful about generalizing too much from this. Clearly people do take notes, comment, & highlight on things they read, so isn’t it really about being where that happens? Journal article pages aren’t where that happens, but we’ve known that for years now. Wasn’t there even a piece here on that from a few years ago?

My experience with Mendeley indicates that the problem is more in the design of the system than any larger structural issue like incentives. I came to this understanding from seeing how readily readers engage with the in-app PDF annotation tool at Mendeley, and from watching the growth of the scholarly community at http://hypothes.is

I do think an earlier commenter here has a point about the expected audience for a comment, and I would generalize that as a kind of risk/reward calculation. Knowing your comment will be seen & will help someone is a reward. Spending time & having the possibility of blowback is a risk. There are things one can do to strike a better risk/reward balance, most importantly making article annotations interoperable. Right now, our comment systems are like email that can’t be sent between providers. Imagine how well Gmail would have taken off if you could only email other Gmail users!

There’s a group of people working on this & we’d welcome more interest! https://hypothes.is/annotating-all-knowledge/

I can’t say I agree with the notion that the only reason commenting isn’t widespread is a technological one. This is the same technologist approach that we’ve been hearing for the last decade and a half — if I build a cool new technology, everyone will change their behavior to use it, which has fallen flat over and over again. It did remind me of a couple of dusty old TSK pieces that hold up well even today:

2010’s “Culture Trumps Technology: The UC Berkeley Scholarly Communication Report”

https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2010/02/15/culture-trumps-technology/

and 2012’s “IT Arrogance vs. Academic Culture — Why the Outcome Is Virtually Certain”

https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2012/04/30/information-technology-arrogance-vs-academic-culture-why-the-outcome-is-virtually-certain/

Asking academia to radically change its practices in order to fit in with the workings of a new piece of technology is a failed approach. If you want to change the culture, you need to work on changing the culture, rather than assuming everyone will flock to a clever new interface. It’s far better to build a tool to meet a disciplinary need rather than hoping the discipline will change in order to use your tool.

It’s nice to see an updated take on this data!

As William has suggested I don’t think it’s true that fewer people want to comment on papers though (at least not in the looser sense). It’s just that for various reasons researchers don’t want to do it on the actual journal site. There’s no control over the presentation, your personal brand isn’t on show, they’re normally hidden away, you can’t easily take it down or edit your comment if you change your mind…. all that was true back in 2009, when there were e.g. hundreds of blog posts about papers in Cell but only a handful of comments on the Cell website, and it’s still true now.

This is most obvious when you look at Twitter (lots of people make “nice paper” type comments about papers), but there’s been growth even in more substantive outputs. For example, in the altmetric.com system there were 287k blog posts mentioning research articles in 2018, up from 222k in 2015. There are more papers published each year, too, of course.

How many of those blog posts are detailed or considered enough to be useful for peer review is maybe a different matter. 🙂

Bravo hypothes.is! The future is yours! And you rescued the 7000 comments the earlier commentator referred to above. Otherwise, the comments would still be resting in the so-difficult-to-access Excel files to which the NCBI consigned them.

What? An important study on an OA journal isn’t OA itself? There’s irony here! Somebody lean on SAGE.

I think that most people commenting on a journal article will be commenting on specific points within it – the methods used, specific data points, conclusions reached etc. However, in the mainstream press, especially newspaper sites, people commenting are more likely to be commenting on the overall view or concept being expressed. This is why annotation services such as hypothes.is are far better suited to the journal article, whereas below-line commenting is far better suited to news sites.

Also, there is a definite sense in which commenting is considered tainted precisely because of what we’ve seen in the un- (or very loosely) moderated mainstream media. Researchers whose careers depend on *everything* they write – not just published research – don’t want their careers derailed by becoming involved in a pile-on, even if there is a difference between perception (discussion will become heated like the mainstream press) and reality (usually, it doesn’t, or at least not to that extreme).

We very much appreciate all the feedback in this comment section.

There is an OA version of the paper available on the White Rose repository – http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/138717/.

We are in agreement with Alison that the results of our study (and others) should not be cause to abandon the notion of community commenting and reviewing altogether. Clearly there is a lot of interesting work being done to explore other ways of supporting commentary, at different stages of the publication process. It may be that these alternative approaches fit better with existing academic practice, or offer greater incentive to researchers (thereby shifting the risk/reward balance noted by William).

And as a final note, it struck us as interesting that the twenty or so comments about our research made here – which almost certainly represent the most substantive online discussion of the article – will not be captured by any formal metric, nor be easily discoverable by anyone reading the paper itself. So there would seem to be a place for new technical solutions to these issues of interoperability and aggregation, too.