Unbundling and rebundling are happening in different parts of college and university education, through new forms of teaching and learning provision and in different parts of the degree path, in every dimension and aspect—creating a complicated environment in an educational sector that is already in a state of disequilibrium.

Unbundling and rebundling are terms that have become more widespread in the last few years, in articles in the Chronicle of Higher Education, Forbes, Huffington Post, and EDUCAUSE Review.1 But these terms do not come from higher education; their original source is the banking industry. An online search for unbundling and rebundling today will lead to results not only in banking but also in the computer industry, legal services, and of course, the music industry. Relatively recently, these concepts have become realities in higher education—at a time when state funding for education is decreasing, higher education tuitions are increasing in many parts of the world, and student numbers and demographics are changing as well.

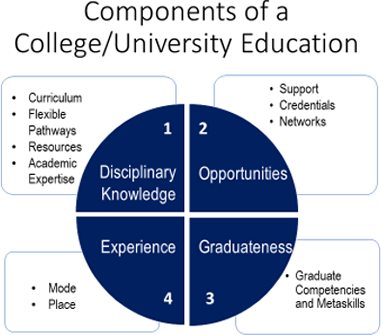

Very simply, I'm using the term unbundling to mean the process of disaggregating educational provision into its component parts, very often with external actors.2 And I'm using the term rebundling to mean the reaggregation of those parts into new components and models. Both are happening in different parts of college and university education, and in different parts of the degree path, in every dimension and aspect—creating an extraordinarily complicated environment in an educational sector that is already in a state of disequilibrium.

Unbundling doesn't simply happen. Aspects of the higher education experience disaggregate and fragment, and then they get re-created—rebundled—in different forms. And it's the re-creating that is especially of interest. What does this all look like? Let's start with what's happening in the area of disciplinary knowledge: curriculum; flexible pathways; resources; and academic expertise.

Disciplinary Knowledge

Curriculum

Curriculum is at the heart of what we do in teaching and learning in higher education. Traditional, residential higher education institutions offer formal, credit-bearing curricula with lectures, tutorials, and seminars. They also offer semi-formal forms of delivery such as short courses as well as non-formal offerings such as summer school or public lectures. Recently there has been expansion into that non-formal space, especially with massive open online courses (MOOCs). Five years ago, MOOCs were completely in the non-formal space, but this has changed. What's particularly interesting now is the intersection between non-formal, semi-formal, and formal. This interface at the blurring of boundaries is where innovative forms of access and new models of provision are emerging.

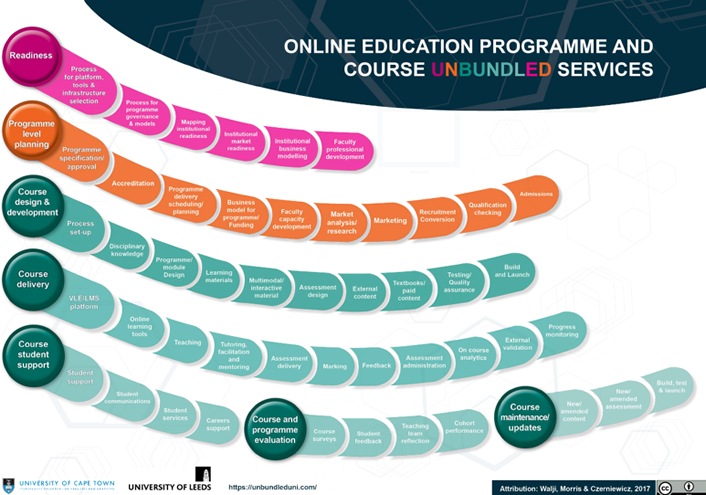

What is also happening in the online sphere is that the different dimensions of teaching courses and programs are separating out or disaggregating. These dimensions comprise various granular components: e-readiness; program-level planning; course design and development; course delivery; course student support; course and program evaluation; and course maintenance/updates. Every single component within those dimensions can be offered by a different provider or vendor as a single service or as multi-services. This has serious implications for platforms, for practices, and for assumptions about students' abilities. This separation of the different dimensions is adding to the complicated nature of the student experience and to the assumptions we make about the students who will have to cope in an increasingly blended and online system. Students will need complex digital literacies to negotiate these new forms of curriculum provision.

The curriculum landscape is deeply entrenched and is very slow to change.3 The critical shift from informal to formal involves boundary-crossing and fuzziness. We have to ask ourselves: Whose interests will these new forms of curriculum provision serve? Which kinds of students are going to benefit? In which places? For what types of institutions? And at the same time that how the curriculum is provided is changing, there is a great deal of work still going on to change the nature—the what, the content—of the curriculum. These issues include transformation and decolonization, surfacing the student voice as well as humanizing the curriculum experience.

Resources

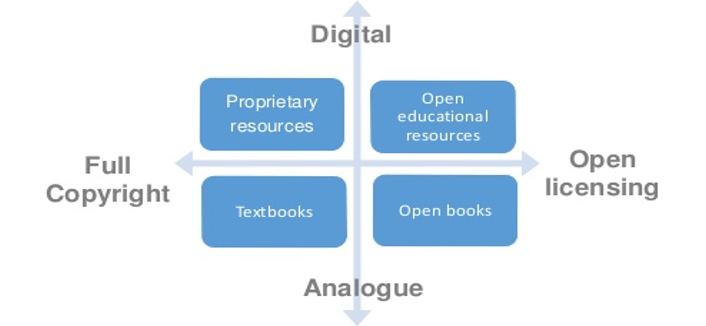

Teaching and learning resources are also being unbundled. They're becoming more granular, multifaceted, and multimodal. They're becoming more complex. They're becoming more modular. Resources fall across axes of different kinds of intellectual property regimes and governance structures: digital versus analog; full copyright versus open licensing. Depending on those intellectual frameworks, how the unbundling and the rebundling happens will be different.

We're seeing different experiments and models for resource provision, including the subscription model: access while you pay. Proprietary textbook options now include—an "all-in-one" digital subscription. Users pay a license and can get everything (whatever that means) for as long as they pay. When they stop paying, access stops, unlike with traditional models of ownership.4 So Netflix comes to higher education, and students no longer own their own textbooks. This kind of rebundling offers more for the duration but works only for those who can keep paying.

There are also original resource innovations using commons models based on open licenses, enabling ongoing free use for all, often with adaptation rights too.5 A popular approach in this space is the freemium model—that is, something that is partially free and partially open and partially paid for. This model is usually promoted as something of great value and of great good, but we should ask: Is it? And when is it advantageous? To whose advantage is a freemium model? Who can afford to pay? Is it unfair to offer something that is only partially free—fully available only to those who can pay?

Auditing and free MOOCs are on their way out. When a participant joins a MOOC today, it's really quite an effort to participate in the free version (when a free version is still available). There are so many moments to pay that the participant needs to be aware that it's actually possible to audit the MOOC and participate for free. Is the promise of free access dead in the MOOC sphere? What are the implications of the shift to a licensing model? This signal from an "open" approach to one similar to the entertainment or music model of access—with access available only while a user pays—raises equity concerns for those who argue for MOOCS as democratic, public-interest models of innovations in provision.

This raises an interesting dilemma in the MOOC sphere. Some providers offer full financial aid. So there's no auditing, and participants can do everything as well as get a certificate. That's a good thing, isn't it? But what about the politics of having to ask for access, of having to declare poverty? This uncovers the complexities of charity; is receiving financial aid a preferable solution for those who are trying to gain access and be sure of full participation?

Flexible Pathways

One of the important promises of an unbundled higher education environment is that of flexible pathways. Ease of access—ease of movement, portability, mobility—is much touted. This can be seen in the formal sphere, for example in initiatives where students can exchange courses and move within the sector: "California Community Colleges, the nation's largest system with 113 institutions," launched a course exchange "so students at one campus can take classes online at another if those courses aren't available on their home turf." California began its Online Education Initiative in late 2013, including "building an online course exchange and creating additional services like counseling to support students in online classes."6 Flexible pathways enacted.

Further flexibility is exemplified by MOOCs and microcredentials (such as nanodegrees), which MOOC providers are developing: these enable students to collect credits that will take them from the non-formal into formal spheres. Their credits can be counted so that they don't have to pay as much and don't have to take all of the courses in the formal sector. This is a real opportunity and a significant shift away from the way things have always been done, especially for expensive postgraduate programs.

Until you look at the numbers. In one example, 323 people out of 34,086 were able to take advantage of MOOC credits.7 Is that really a form of access? On the one hand it is, because 323 people gained access—people who wouldn't have gained access to a program that might otherwise have had 20 students. On the other hand, this is an incredibly small fraction: 1 percent. How widespread will this become? It is not clear yet, which is why this is such an exciting and emergent space.

All of this raises questions not just about access but about success. Access is only entrance—allowing someone to join the party, to get into the system. What about succeeding in the system? How are students going to succeed in the college/university of the future with hybrid online/non-online courses centered around students with credits accruing from multiple schools, in alternating periods of attendance and absence?8 How are students going to have coherent educational experiences? What kinds of cultural capital do they need to negotiate such an experience? These are the harder questions to answer.

Academic Expertise

Both the academic expert and academic expertise are becoming unbundled as well, giving rise to new roles, including the rise of the para-academic.9 This is happening at the same time that academia itself is going part-time and becoming less secure.10 We're seeing the growth of the academic precariat, with all the worrying implications that has not only for a decent and humane working life for academics but also for robust knowledge production and dissemination and for the coherence of the student experience.

Finally, does the automation of the professions apply to academia?11 I think it does. Roles and activities are already being transformed—humans can be replaced by chatbots offering robotic tutoring, and the holy grail of automated marking is being pursued as digitally mediated rebundled teaching is reimagined. My question here is: In an age of adaptive learning, how will an increasingly fragmented, dispersed, and precarious academic body share knowledge with and enable a coherent, caring, and supportive learning experience to all students?

Opportunities

A college/university education affords the opportunities of support, credentials, and networks.

Support

Learning support is expensive. The challenge is to remove that cost without impacting access and quality. The new environment, unbundling, and adaptive learning promise to remove that cost. And we've seen this promise: "The term [MOOC] applies to any course offered free, online and at scale. What marks the MOOC out from conventional online learning is that no professional academic time (or virtually none) is allocated to guiding or supporting individual learners."12

But is access without support opportunity? Vincent Tinto argues not: "Effective student support does not arise by chance. It requires intentional, structured, and proactive action that is systematic in nature and coordinated in application."13 Paying attention to support is essential to an equity perspective on education. The legislation in South Africa, for one, makes this absolutely clear. The goal is to "promote equity of access and fair chances of success to all who are seeking to realise their potential through higher education."14

Just to provide one example from South Africa, of students in contact (face-to-face) mode, 63.6 percent had graduated after ten years of study. Of students in distance mode, only 14.8 percent had graduated after ten years.15 While not all distance education is online, there is much to be learned from decades of distance education experience. Moving into the online sphere has profound implications for those who are committed to successful education for all. Online is neither easy nor trivial. But of course support is also a market opportunity. The number-one area of investment in educational technology is in learning support.16

In addition, support is being automated. Learning analytics and adaptive learning promise to automate support and to replace "pastoral care." But the dangers of automated support can be severe. The risk is a differentiated system in which the poor will have the support of machines and algorithms while the rich will have face-to-face and paid support. Is there an alternative? How can the affordances of new technologies be exploited and leveraged to ensure appropriate, affordable, and caring support for all?

Credentials

Credentials and new forms of credentialing are central to how unbundling and rebundling are being enacted. As Sean Gallagher notes: "The traditional boundaries are blurring between professional development, occupational credentialing and formal higher education."17 We are seeing the intensification of new forms of agreement around competence and status, including not only credentials but also micro-credentials, "nano"-degrees, and badges (digital badges, open badges). This may even lead to omitting the college/university altogether as educators and organizations collaborate and use their own forms of credentials.

The battle for new forms of legitimacy is central, and the jury is still out. Credible commentators in higher education do not agree. Sociology Professor Tressie McMillan Cottom states: "There is little evidence that the labor market values most of these new credentials." On the other hand, Michael Feldstein argues that digital badges, at least, are gaining traction: "They seem to be filling in cracks that more formal credentials don't cover."18

Certification is an equity issue. For most people, getting verifiable accreditation and certification right is at the heart of why they are invested in higher education. Credentials may prove to be the real equalizers in the world of work, but they do raise critical questions about the function and the reputation of the higher education institution. They also raise questions about value, stigma, and legitimacy. A key question is, how can new forms of credentials increase access both to formal education and to working opportunities?

Networks

Finally, a third opportunity involves social networks and social capital. Residential colleges and universities are sites of peer interaction and the development of social networks and social capital. What will the potential differentiation of the system mean for how social capital is imbued and gained? Will the elite residential institutions be the ones to inculcate and enable the networks of social capital? How will students who are outside that system gain social capital? Can valuable networks be built in rebundled digitized environments? Or will "bricks for the rich and clicks for the poor" mean that they will be effectively locked out?

Graduateness

Graduate Competencies and Metaskills

What does it mean to be a graduate in this environment in which "graduateness" is a brand? For many employers, what students have studied is not the issue; many employers are more concerned with where students have studied. The brand of the institution signals a particular kind of graduate. Attributes and literacies are assumed as a result of co-curricular experiences. Students and parents know this. So what does an increasingly object-oriented, competency-based unbundled higher education mean for the notion of graduateness?

Experience

Mode

Online is now close to mainstream. In the United States, more than 30 percent of higher education students are enrolled in at least one online course.19 In our research, one senior academic stated: "I think online is the future of universities. Because of the financial strain, because of the fact that we live in a global community. Perish the thought but I think that is going to happen."20 Willingly or unwillingly, we're headed that way.

The online mode is also creating new functions and capabilities. Online courses require different and often expensive types of work including professional development, technologies, design course/program specifications, instructional design, learning materials, student identity verification, assessments, accessibility, and accreditation. And online is producing not only new market opportunities and new enabler companies but also new relationships: with private companies as partners or service providers and through both outsourcing and insourcing.

The online mode is creating a differentiated system, with diversified offerings for different groups. For example, the University of Pennsylvania's Wharton School offers an MBA degree, in various formats. In an analysis of 875,000 students in 9 MOOCs, a higher percentage of foreign-born students, of unemployed students, and of underrepresented minorities enroll through the MOOCs.21 Depending on your view, that is either an increase in access or an increase in marginalization, representing a differentiated system that is keeping those students out of the mainstream experience. Which is it? The answer is not straightforward.

Equity considerations abound. One large-scale U.S. survey of 40,000 students in nearly 500,000 online courses found that all students suffered in performance in online courses. However, some struggled more than others: males, younger students, black students, and students with lower grade point averages. Other research found that online courses were not working well at community colleges, where 11 percent of the students were less likely to pass an online version of the same course. Retention too can be worse in online courses. So, it seems that online courses as they are currently designed don't always deliver on their promise of expanding access to higher education.22

Indeed, online courses are not always favored by those for whom those good intentions are offered. A British Council study of Syrian refugees found that they believed that the people who taught those online courses were not as good as face-to-face teachers. And they were, once again, concerned with the matter of accreditation.23 The online space is clearly rife with complex and profound issues raised by equity and by increasingly pervasive private/public partnerships: new and changing roles and responsibilities; ownership of the academic project; academic identity and responsibility; the impact of commercial values on teaching and learning; as well as emergent values needing close interrogation.

Place

Place is being replaced by platform, by new learning environments. What does this mean for the student experience? What kind of identity and community is possible in cyberspace? What is a sense of place in the online sphere?

Online shifts the focus and the potential beyond the local. Providers are competing for the growing global middle class. The middle class is anticipated to comprise two-thirds of the world's population by 2025, with emerging economies expected to increase their share of the global medium-high, middle-class, and affluent segments from 24 percent in 2000 to 67 percent by 2025 (or by 2 billion people). The African middle class tripled from 2000 through 2014.24

Technology and market liberalization thus open up opportunities to pursue the broader conceptual opportunity of the "borderless" student population. With the intense competition for capable moneyed students from everywhere in the world, and with the options for these students to apply to any provider anywhere, where does that leave those without financial resources? Who is responsible for everyone else? Is the local college or university left to provide education for the have-nots while the haves go online to more prestigious educational providers from other countries? Or will rebundling see the elite remain residential while the rest go online locally?

Unbundling and Rebundling: Opportunity or Threat?

The first problem when debating whether unbundling and rebundling are opportunities or threats is that the associated words themselves have different meanings depending on the agenda being promoted. For example, flexibility can mean convenient and mobile, but it can also mean incoherent, fragmented, and difficult for those without cultural capital. Sharing can mean generosity, openness, and opportunity, but the sharing economy is known to be exploitative. It's a gig economy. How could that sharing economy be appropriate in higher education? There are indications that this is already a danger of a disjointed unbundled higher education learning experience. Indeed, the notion of a value propositionis contested. Are we talking about a return on investment, or are we talking about the creation of social citizenship? These terms are all semantic bleaching.

The unbundling/rebundling debate speaks to the battle for the soul of the college/university. Are higher education institutions going to become businesses specializing in preparing people to work in businesses? Or are they going to be places that create citizens with humane perspectives and critical stances serving the public interest? This is the tension that is being manifest in the trends noted above.

The unbundling/rebundling debate also speaks to the relationship between the market, the state, and the commons. It is essential to consider rebundling in the light of the possibilities of the commons. At the moment, arguably, the marketized approach to higher education—or social imaginary—is dominant. What has happened is that the market-led approaches have recognized the opportunities that unbundling and rebundling provide and have found ways to monetize every single aspect listed so far, including graduate capabilities, support, credentials, networks, disciplinary knowledge, opportunities, experience, graduateness, mode, place, curriculum, learning pathways, resources, and academic expertise.

This raises some critical questions. Who's doing this monetizing? Why? For what purpose? Which types of knowledge are being valued? What is considered "valuable" in higher education? What is the meaning of the academic "brand"? Who is regulating and shaping those markets? And why is this all so urgent now?

Still, can higher education be a "real" market? Here, Simon Marginson's work is helpful. He argues that it would be very difficult for higher education to become a real market in the same way as banking, for example. Why? First, because knowledge is a public good despite all attempts to make it a private good. It is non-rivalrous and non-excludable. It is not clear exactly what the product is. Second is the role of status competition: higher education is one of the few areas where the consumer brings something to the relationship. Third is the role of rankings, fixed and selective: non-elite institutions cannot entice elite customers simply by dropping the price for the same service. They don't have the right brand.25

A final consideration is the role and responsibility of the state. There has always been a relationship between the state and the market. There's nothing new about that relationship. What is new is the question of who has control of that role and relationship. The pendulum has swung. Who determines the priorities for market behavior? Who defines the objectives? Who makes the decisions? Who regulates and shapes? What is gained, and what is lost—and by whom?

The terms of the relationship matter. Mahmood Mamdani has written extensively about this in his book Scholars in the Marketplace and elsewhere. He talks about "soft versions" of the relationship, in which the public university sets the terms, and "hard versions," in which the private sector sets the terms. And he discusses limited privatization, the critical appropriation of the market for public ends, and commercialization, the appropriation of the public for private ends.26

Higher education is a hybrid ecology. Other possibilities for shaping provision include the model of the commons. The idea of the commons places knowledge and educators as knowledge producers in charge at the center, in a shared understanding. This approach foregrounds co-creation and participation. It develops governance mechanisms premised on shared resources. And it shifts the discourse from a market-led higher education knowledge economy to an open, collaborative, learning-led knowledge society.

How can the market be regulated in unequal contexts to serve the public good? I believe the answer is through appropriating commons approaches to higher education and through reasserting the role of the state, which has been systematically underfunding the higher education sector. The state has too often abdicated its role as regulator and ensurer of higher education as a public good. It is the state that needs to mediate and shape the possibilities of the market and the role of the private nature of higher education. Despite all the challenges, it is the state that has the primary responsibility to ensure that redress, successful participation, and disadvantage are addressed. If unbundling and rebundling are to serve the needs of a knowledge society for the good of all, how can the state enable the requirements of socially responsible public education for a democratic citizenship?

Conclusion

It is not inevitable that profit making will determine how unbundling and rebundling in higher education will play out. The situation is dynamic, in flux, and highly contested; it is being negotiated and renegotiated right now. Unbundling and rebundling in teaching and learning are about power and contestations. Emergent models and innovations are appropriated by competing discourses and agendas. Is it a problem or a solution? As part of the problem, unbundling and rebundling may serve the interests of the few rather than the many and may serve the private good at the expense of the public good. The risks are many, including fragmentation in higher education, leading to an incoherent student experience, and monopolization of the higher education sector by a few companies, just as has happened in other sectors.

But I'd like to conclude on a hopeful note. Unbundling and rebundling can be part of the solution and can offer opportunities for reasonable and affordable access and education for all. Unbundling and rebundling are opening spaces, relationships, and opportunities that did not exist even five years ago. These processes can be harnessed and utilized for the good. We need to critically engage with these issues to ensure that the new possibilities of provision for teaching and learning can be fully exploited for democratic ends for all.

Notes

- Goldie Blumenstyk, "Why Georgetown's Randy Bass Wants to 'Rebundle' College," Chronicle of Higher Education, May 25, 2016; Michael Horn, "Unbundling and Re-bundling in Higher Education," Forbes, July 10, 2014; Anant Agarwal, "Unbundled: Reimagining Higher Education," Huffington Post, December 9, 2013 (updated February 8, 2014); Ryan Craig and Allison Williams, "Data, Technology, and the Great Unbundling of Higher Education," EDUCAUSE Review 50, no. 5 (September/October 2015); Audrey Watters, "Unbundling and Unmooring: Technology and the Higher Ed Tsunami," EDUCAUSE Review 47, no. 4 (July/August 2012). ↩

- See "The Unbundled University: Researching Emerging Models in an Unequal Landscape" [https://unbundleduni.com/] website, a 26-month project of the ESRC (Economic & Social Research Council), the NRF (National Research Foundation), the University of Cape Town, and the University of Leeds. ↩

- Laura Czerniewicz, Andrew Deacon, Janet Small, and Sukaina Walji, "Developing World MOOCs: A Curriculum View of the MOOC Landscape," Journal of Global Literacies, Technologies, and Emerging Pedagogies 2, no. 3 (2014). ↩

- Michael Feldstein, "Cengage Unlimited Draws the Battle Lines in the Curricular Materials War," e-Literate, January 7, 2018. ↩

- The book Made with Creative Commons (2017) showcases a variety of resources that have been made available with Creative Commons licenses through open approaches. ↩

- Marguerite McNeal, "California Launches the Nation's Largest Community College Course Exchange," EdSurge, January 24, 2017. ↩

- Carl Straumsheim, "Less Than 1%," Inside Higher Ed, December 21, 2015. ↩

- Clay Shirky, "The Digital Revolution in Higher Education Has Already Happened; No One Noticed," Medium, November 6, 2015. ↩

- Bruce Macfarlane, "The Morphing of Academic Practice: Unbundling and the Rise of the Para-Academic," Higher Education Quarterly 65, no. 1 (January 2011). ↩

- David F. Ruccio, "Academic Precariat," Real-World Economics Review Blog, April 16, 2017. ↩

- Richard Susskind and Daniel Susskind, The Future of the Professions: How Technology Will Transform the Work of Human Experts (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015). ↩

- "The Maturing of the MOOC: Literature Review of Massive Open Online Courses and Other Forms of Online Distance Learning," BIS Research Paper Number 130 (London: Department for Business, Innovation and Skills, September 2013), p. 10. ↩

- Vincent Tinto, "Lessons Learned: Access Without Support Is Not Opportunity," Regional Symposia on Student Success, August 19–23, 2013. ↩

- "A Programme for the Transformation of Higher Education," Education White Paper 3 (Pretoria: South African Department of Education, July 24, 1997). ↩

- Republic of South Africa, Department of Higher Education and Training, "2000 to 2008 First Time Entering Undergraduate Cohort Studies for Public Higher Education Institutions," March 31, 2016. ↩

- Audrey Watters, "Top Ed-Tech Trends of 2016: A Hack Education Project," Hack Education, n.d. ↩

- Sean Gallagher, "From Micromasters to Nanodegrees," University World News, no. 423 (August 12, 2016). ↩

- Cottom quoted in Doug Lederman, "Analyzing the Purdue-Kaplan Marriage," Inside Higher Ed, May 3, 2017; Michael Feldstein, "Digital Badges Are Gaining Traction," e-Literate, June 7, 2017. ↩

- Julia E. Seaman, I. Elaine Allen, and Jeff Seaman, Grade Increase: Tracking Distance Education in the United States (Oakland, CA: Babson Survey Research Group, 2018), p. 11. ↩

- South African university academic quoted in L. Czerniewicz, M. Bot, and S. Gordon, "Online Education: Views from Heads of Department," unpublished report, 2015. ↩

- Gayle Christensen, Brandon Alcorn, and Ezekiel J. Emanuel, "MOOCs Won't Replace Business Schools—They'll Diversify Them," Harvard Business Review, June 03, 2014. ↩

- Di Xu and Shanna Smith Jaggars, "Adaptability to Online Learning: Differences across Types of Students and Academic Subject Areas," CCRC Working Paper No 54 (New York: Community College Research Center, Teachers College, Columbia University, February 2013); Jill Barshay, "Five Studies Find Online Courses Are Not Working Well at Community Colleges," The Hechinger Report, April 27, 2015. ↩

- Beckie Smith, "HE Opportunities Limited, Weak, Say Syrian Refugees," The PIE News, May 24, 2017. ↩

- Banco Bilbao Vizcaya Argentaria, "Flourishing Middle Classes in the Emerging World to Keep Driving Reduction in Global Inequality," Eagles Economic Watch, March 2, 2015, cited in Australian International Education 2025; "New Agreement Aims to Expand Online Learning in Africa," ICEF Monitor, February 14, 2017. ↩

- Simon Marginson, "The Impossibility of Capitalist Markets in Higher Education," Journal of Education Policy 28, no. 3 (2013). ↩

- Mahmood Mamdani, Scholars in the Marketplace: The Dilemmas of Neo-Liberal Reform at Makerere University, 1989–2005 (Kampala, Uganda: Fountain Publishers, 2007). ↩

Laura Czerniewicz is the Director of the Centre for Innovation in Learning and Teaching at the University of Cape Town, South Africa. She is the co-Principal Investigator of the Unbundled University [https://unbundleduni.com/] research project.

© 2018 Laura Czerniewicz. The text of this article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

EDUCAUSE Review 53, no. 6 (November/December 2018)