Facebook Only Cares About Facebook

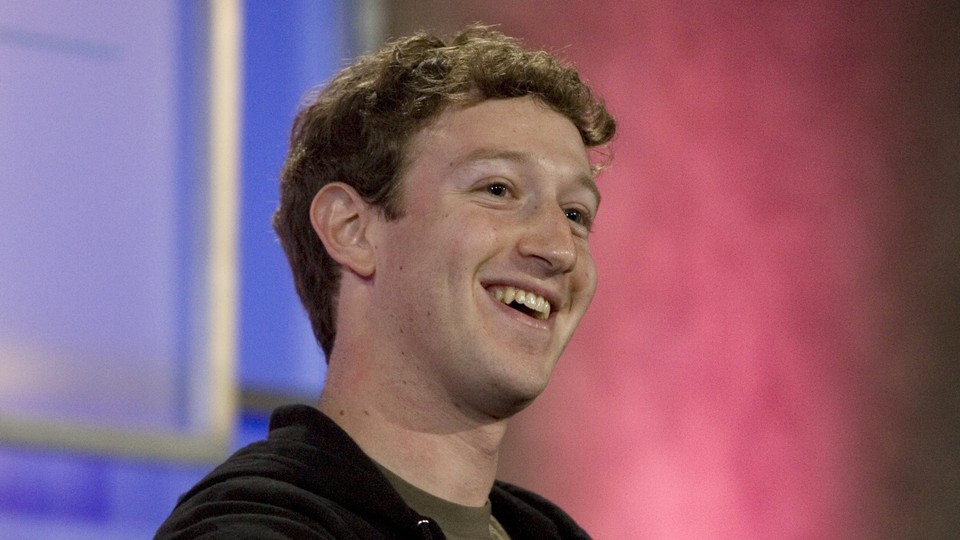

Whatever Mark Zuckerberg says about human community or his legacy, his company is acting in its own interests—and against the public good.

Facebook’s crushing blow to independent media arrived last fall in Slovakia, Cambodia, Guatemala, and three other nations.

The social giant removed stories by these publishers from users’ News Feeds, hiding them in a new, hard-to-find stream. These independent publishers reported that they lost as much as 80 percent of their audience during this experiment.

Facebook doesn’t care. At least, it usually seems that way.

Despite angry pushback in the six countries affected by Facebook’s algorithmic tinkering, the company is now going ahead with similar changes to its News Feed globally. These changes will likely de-prioritize stories from professional publishers, and instead favor dispatches published by a user’s friends and family. Many American news organizations will see the sharp traffic declines their brethren in other nations experienced last year—unless they pay Facebook to include their stories in readers’ feeds.

At the heart of this change is Facebook’s attempt to be seen not as a news publisher, but as a neutral platform for interactions between friends. Facing sharp criticism for its role in spreading misinformation, and possibly in tipping elections in the United States and in the United Kingdom, Facebook is anxious to limit its exposure by limiting its role. It has long been this way.

This rebalancing means different things for the company’s many stakeholders—for publishers, it means they’re almost certainly going to be punished for their reliance on a platform that’s never been a wholly reliable partner. Facebook didn’t talk to publishers in Slovakia because publishers are less important than other stakeholders in this next incarnation of Facebook. But more broadly, Facebook doesn’t talk to you because Facebook already knows what you want.

Facebook collects information on a person’s every interaction with the site—and many other actions online—so Facebook knows a great deal about what we pay attention to. People say they’re interested in a broad range of news from different political preferences, but Facebook knows they really want angry, outraged articles that confirm political prejudices.

Publishers in Slovakia and in the United States may warn of damage to democracy if Facebook readers receive less news, but Facebook knows people will be perfectly happy—perfectly engaged—with more posts from friends and families instead.

For Facebook, our revealed preferences—discovered by analyzing our behavior—speak volumes. The words we say, on the other hand, are often best ignored. (Keep this in mind when taking Facebook’s two-question survey on what media brands you trust.)

Tristan Harris, a fierce and persuasive critic of the ad-supported internet, recently offered me an analogy to explain a problem with revealed preferences. I pledge to go to the gym more in 2018, but every morning when I wake up, my partner presents me with a plate of donuts and urges me to stay in bed and eat them. My revealed preferences show that I’m more interested in eating donuts than in exercising. But it’s pretty perverse that my partner is working to give me what I really crave, ignoring what I’ve clearly stated I aspire to.

Facebook’s upcoming newsfeed change won’t eliminate fake news ... at least, it didn’t in Slovakia. People share sensational or shocking news, while more reliable news tends not to go viral. When people choose to subscribe to reliable news sources, they’re asking to go to the gym. With these News Feed changes, Facebook threw out your gym shoes and subscribed you to a donut-delivery service. Why do 2 billion people put up with a service that patronizingly reminds them that it’s designed for their well-being, while it studiously ignores our stated preferences? Many people feel like they don’t have a choice. Facebook is the only social network, for example, where I overlap with some of my friends, especially those from my childhood and from high school.

I don’t want Facebook to go away—I want it to get better. But increasingly, I think the only way Facebook will listen to people’s expressed preferences is if people start building better alternatives. Right now, Facebook chooses what stories should top your News Feed, optimizing for “engagement” and “time well spent.” Don’t like the choices Facebook is making? Too bad. You can temporarily set Facebook to give you a chronological feed, but when you close your browser window, you’ll be returned to Facebook’s paternalistic algorithm.

This fall, my colleagues and I released gobo.social, a customizable news aggregator. Gobo presents you with posts from your friends, but also gives you a set of sliders that govern what news you see and what’s hidden from you. Want more serious news, less humor? Move a slider. Need to hear more female voices? Adjust the gender slider, or press the “mute all men” button for a much quieter internet. Gobo currently includes half a dozen ways to tune your news feed, with more to come. (It’s open-source software, so you can write your own filters, too.) Gobo is a provocation, not a product. While it’s a good tool for reading Twitter, Facebook only allows us to show you Facebook Pages (the pages that are being de-prioritized in the News Feed changes), not posts from your friends, crippling its functionality as a social-network aggregator. Our goal is not to persuade you to read your social media through Gobo (though you’re certainly welcome to try!), but to encourage platforms like Facebook to give their users more control over what they see.

If you want to use Facebook to follow the news, you should be able to, even if Facebook’s algorithms know what really captures your attention. There’s a robust debate about how Facebook should present news to its readers. Should it filter out fake news? Prioritize high-quality news? Focus on friends and family instead of politics? Facebook’s decision to steer away from news is an attempt to evade this challenging debate altogether. And perhaps we were wrong to invite Facebook to this debate in the first place.

Instead of telling Facebook what it should do, people should build tools that let them view the world the way they choose. If regulators force Facebook and other platforms to police news quality, they’ll give more control to a platform that’s already demonstrated its disinterest in editorial judgment. A better path would be to force all platforms to adopt two simple rules:

- Users own their own data, including the content they create and the web of relationships they’ve built online. And they can take this data with them from one platform to another, or delete it from an existing platform.

- Users can view platforms like Facebook through an aggregator, a tool that lets you read social media through your own filters, like Gobo.

The first rule helps solve the problem that Facebook alternatives like Diaspora and Mastodon have faced. People have a great deal of time and emotional energy invested in their online communities. Asking them to throw these connections out and move to another network is a nonstarter. If we can move our data between platforms, there’s the possibility that some of Facebook’s 2 billion users will choose a social network where they have more control over what they read and write. The second rule allows developers to build real customizable aggregators, not toys like Gobo, which would let people control what they read on online platforms—helping them live up to their aspirations, not down to their preferences.

Obviously, Facebook is filled with people who care deeply about these issues. Some are my friends and my former students. But Facebook suffers from a problem of its own success. It has grown so central to our mediated understanding of the world that it either needs to learn to listen to its users’ stated desires, or it needs to make room for platforms that do.