The Algorithm That Makes Preschoolers Obsessed With YouTube

Surprise eggs and slime are at the center of an online realm that’s changing the way the experts think about human development.

Toddlers crave power. Too bad for them, they have none. Hence the tantrums and absurd demands. (No, I want this banana, not that one, which looks identical in every way but which you just started peeling and is therefore worthless to me now.)

They just want to be in charge! This desire for autonomy clarifies so much about the behavior of a very small human. It also begins to explain the popularity of YouTube among toddlers and preschoolers, several developmental psychologists told me.

If you don’t have a 3-year-old in your life, you may not be aware of YouTube Kids, an app that’s essentially a stripped-down version of the original video blogging site, with videos filtered by the target audience’s age. And because the mobile app is designed for use on a phone or tablet, kids can tap their way across a digital ecosystem populated by countless videos—all conceived with them in mind.

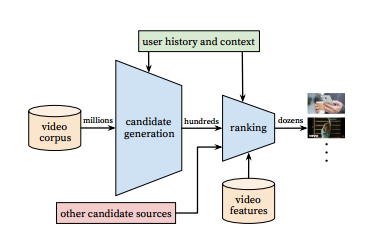

The videos that surface on the app are generated by YouTube’s recommendation algorithm, which takes into account a user’s search history, viewing history, and other data.* The algorithm is basically a funnel through which every YouTube video is poured—with only a few making it onto a person’s screen.

This recommendation engine poses a difficult task, simply because of the scale of the platform. “YouTube recommendations are responsible for helping more than a billion users discover personalized content from an ever-growing corpus of videos,” researchers at Google, which owns YouTube, wrote in a 2016 paper about the algorithm. That includes many hours of video uploaded to the site every second of every day. Making a recommendation system that’s worthwhile is “extremely challenging,” they wrote, because the algorithm has to continuously sift through a mind-boggling trove of content and instantly identify the freshest and most relevant videos—all while knowing how to ignore the noise.

And here’s where the ouroboros factor comes in: Kids watch the same kinds of videos over and over. Videomakers take notice of what’s most popular, then mimic it, hoping that kids will click on their stuff. When they do, YouTube’s algorithm takes notice, and recommends those videos to kids. Kids keep clicking on them, and keep being offered more of the same. Which means video makers keep making those kinds of videos—hoping kids will click.

This is, in essence, how all algorithms work. It’s how filter bubbles are made. A little bit of computer code tracks what you find engaging—what sorts of videos do you watch most often, and for the longest periods of time?—then sends you more of that kind of stuff. Viewed a certain way, YouTube Kids is offering programming that’s very specifically tailored to what children want to see. Kids are actually selecting it themselves, right down to the second they lose interest and choose to tap on something else. The YouTube app, in other words, is a giant reflection of what kids want. In this way, it opens a special kind of window into a child’s psyche.

But what does it reveal?

“Up until very recently, surprisingly few people were looking at this,” says Heather Kirkorian, an assistant professor of human development in the School of Human Ecology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. “In the last year or so, we’re actually seeing some research into apps and touchscreens. It’s just starting to come out.”

Kids’ videos are among the most watched content in YouTube history. This video, for example, has been viewed more than 2.3 billion times, according to YouTube’s count:

You can find some high-quality animation on YouTube Kids, plus clips from television shows like Peppa Pig, and sing-along nursery rhymes. “Daddy Finger” is basically the YouTube Kids anthem, and ChuChu TV’s dynamic interpretations of popular kid songs are inescapable.

Many of the most popular videos have an amateur feel. Toy demonstrations like surprise-egg videos are huge. These videos are just what they sound like: Adults narrate as they play with various toys, often by pulling them out of plastic eggs or peeling away layers of slime or Play-Doh to reveal a hidden figurine.

Kids go nuts for these things.

Here’s a video from the YouTube Kids vloggers Toys Unlimited that’s logged more than 25 million views, for example:

The vague weirdness of these videos aside, it’s actually easy to see why kids like them. “Who doesn’t want to get a surprise? That’s sort of how all of us operate,” says Sandra Calvert, the director of the Children’s Digital Media Center at Georgetown University. In addition to surprises being fun, many of the videos are basically toy commercials. (This video of a person pressing sparkly Play-Doh onto chintzy Disney princess figurines has been viewed 550 million times.) And they let kids tap into a whole internet’s worth of plastic eggs and perceived power. They get to choose what they watch. And kids love being in charge, even in superficial ways.

“It’s sort of like rapid-fire channel surfing,” says Michael Rich, a professor of pediatrics at Harvard Medical School and the director of the Center on Media and Child Health. “In many ways YouTube Kids is better suited to the attention span of a young child—just by virtue of its length—than something like a half-hour or hour broadcast program can be.”

Rich and others compare the app to predecessors like Sesame Street, which introduced short segments within a longer program, in part to keep the attention of the young children watching. For decades, researchers have looked at how kids respond to television. Now they’re examining the way children use mobile apps—how many hours they’re spending, which apps they’re using, and so on.

It makes sense that researchers have begun to take notice. In the mobile internet age, the same millennials who have ditched cable television en masse are now having babies, which makes apps like YouTube Kids the screentime option du jour. Instead of being treated to a 28-minute episode of Mr. Rogers’s Neighborhood, a toddler or preschooler might be offered 28 minutes of phone time to play with the Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood app. Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood is a television program, too—a spin-off of Mr. Rogers’s—aimed at viewers aged 2 years old to 4 years old.

But toddlers and preschoolers are actually pretty separate groups, as far researchers are concerned. A 2-year-old and a 4-year-old might both like watching Daniel Tiger, or the same YouTube Kids video, but their takeaway is apt to be much different, Kirkorian told me. Children under the age of 3 tend to have difficulty taking information relayed to them through a screen and applying it to real-life situations. Many studies have reached similar conclusions, with a few notable exceptions. Researchers recently discovered that when a screentime experience becomes interactive—Facetiming with Grandmère, let’s say—kids under 3 years old actually can make strong connections between what’s happening onscreen and offscreen.

Kirkorian’s lab designed a series of experiments to see how much of a role interactivity plays in helping a young child transfer information this way. She and her colleagues found striking learning differences among what young children learned—even kids under 2 years old—when they could interact with an app versus when they were just watching a screen. Other researchers, too, have found that incorporating some sort of interactivity helps children retain information better. Researchers at different institutions have different definitions of “interactivity,” but in one experiment it was an act as simple as pressing a spacebar.

“So there does seem to be something about the act of choosing, having some kind of agency, that makes a difference for little kids,” Kirkorian says. “The speculative part is why that makes a difference.”

One idea is that kids, especially, like to watch the same things over and over and over again until they really understand it. I watched the Dumbo VHS so many times as a little kid that I would recite the movie on long car rides. Apparently, this is not unusual—at least not since the age of VCRs and, subsequently, on-demand programming and apps. “If they have the opportunity to choose what they’re watching, then they’re likely to interact in a way that meets their learning goals,” Kirkorian says. “We know the act of learning new information is rewarding, so they’re likely to pick the information or videos that are in that sweet spot.”

“Children like to watch the same thing over and over,” says Calvert, of Georgetown. “Some of that is a comprehension issue, so they’ll repeatedly look at it so they can understand the story. Kids often don’t understand people’s motives, and that’s a major driver for a story. They don’t often understand the link between actions and consequences.”

Young kids are also just predisposed to becoming obsessive about relatively narrow interests. (Elephants! Trains! The moon! Ice cream!) Around the 18-month mark, many toddlers develop “extremely intense interests,” says Georgene Troseth, an associate professor of psychology at Vanderbilt University. Which is part of why kids using apps like YouTube Kids often select videos that portray familiar concepts—ones that feature a cartoon character or topic they’re already drawn to. This presents a research challenge, however. If kids are just tapping a thumbnail of a video because they recognize it, it’s hard to say how much they’re learning—or how different the app environment really is from other forms of play.

Even the surprise-egg craze isn’t really novel, says Rachel Barr, a developmental psychologist at Georgetown. “They are relatively fast-paced and they include something that young children really like: things being enclosed and unwrapped,” she told me. “I have not tested it, but it seems unlikely that children are learning from these videos since they are not clearly constructed.”

“Interactivity is not always a good thing,” she added.

Researchers differ on the degree to which YouTube Kids is a valuable educational tool. Obviously, it depends on the video and the involvement of a caregiver to help contextualize what’s on screen. But questions about how the algorithm works also play a role. It’s not clear, for instance, how heavily YouTube weighs previous watching behaviors in its recommendation engine. If a kid binge-watches a bunch of videos that are lower quality in terms of learning potential, are they then stuck in a filter bubble where they’ll only see similarly low-quality programming?

There isn’t a human handpicking the best videos for kids to watch. The only human input on YouTube’s side is to monitor the app for inappropriate content, a spokesperson for YouTube told me. Quality control has still been an issue, however. YouTube Kids last year featured a video that showed Mickey Mouse-esque characters shooting one another in the head with guns, Today reported.

“The available content is not curated but rather filtered into the app via the algorithm,” said Nina Knight, a YouTube spokesperson. “So unlike traditional TV, where the content is being selected for you at a specified time, the YouTube Kids app gives each child and family more of the type of content they love and anytime they want it, which is incredibly unique.”

At the same time, the creators of YouTube Kids videos spend countless hours trying to game the algorithm so that their videos are viewed as many times as possible—more views translate into more advertising dollars for them. Here’s a video by Toys AndMe that’s logged more than 125 million views since it was posted in September 2016:

“You have to do what the algorithm wants for you,” says Nathalie Clark, the co-creator of a similarly popular channel, Toys Unlimited, and a former ICU nurse who quit her job to make videos full-time. “You can’t really jump back and forth between themes.”

What she means is, once YouTube’s algorithm has determined that a certain channel is a source of videos about slime, or colors, or shapes, or whatever else—and especially once a channel has had a hit video on a given topic—videomakers stray from that classification at their peril. “Honestly, YouTube picks for you,” she says. “Trending right now is Paw Patrol, so we do a lot of Paw Patrol.”

There are other key strategies for making a YouTube Kids video go viral. Make enough of these things and you start to get a sense of what children want to see, she says. “I wish I could tell you more,” she added, “But I don’t want to introduce competition. And, honestly, nobody really understands it. ”

The other thing people don’t yet understand is how growing up in the mobile internet age will change the way children think about storytelling. “There’s a rich set of literature showing kids who are reading more books are more imaginative,” says Calvert, of the Children’s Digital Media Center. “But in the age of interactivity, it’s no longer just consuming what somebody else makes. It’s also making your own thing.”

In other words, the youngest generation of app users is developing new expectations about narrative structure and informational environments. Beyond the thrill a preschooler gets from tapping a screen, or watching The Bing Bong Song video for the umpteenth time, the long-term implications for cellphone-toting toddlers are tangled up with all the other complexities of living in a highly networked on-demand world.

* Unlike YouTube’s main website, YouTube Kids does not use an individual child’s geographic location, gender, or age to make recommendations, a spokesperson told me. YouTube Kids does, however, ask for a user’s age range. The YouTube spokeswoman cited the Children's Online Privacy Protection Rule, a Federal Trade Commission requirement for operators of websites aimed at kids under 13 years old, but declined to answer repeated questions about why the YouTube Kids algorithm used different inputs than the original site’s algorithm.