Most research on news consumption annoys me. Most research on news consumption – like Pew’s State of the News Media – relies on surveys of people self-reporting how they consume news. But surveys can only answer the questions that they ask. And as any journalist with a decent bullshit detector should know: the problem is people misremember, people forget, and people lie.

The most interesting news consumption research uses ethnography: this involves watching people and measuring what they actually do – not what they say they do. To this end AP’s 2008 report A New Model for News is still one of the most insightful pieces of research into news consumption you’ll ever read – because it picks out details like the role that email and desktop widgets play, or the reasons why people check the news in the first place (they’re bored at work, for example).

Now six years on two Dutch researchers have published a paper summarising various pieces of ethnographic and interview-based consumption research (£) over the last decade – providing some genuine insights into just how varied news ‘consumption’ actually is.

Irene Costera Meijer and Tim Groot Kormelink‘s focus is not on what medium people use, or when they use it, but rather on how engaged people are with the news.

To do this they have identified 16 different news consumption practices which they give the following very specific names:

- Reading

- Watching

- Viewing

- Listening

- Checking

- Snacking

- Scanning

- Monitoring

- Searching

- Clicking

- Linking

- Sharing

- Liking

- Recommending

- Commenting

- Voting

Below is my attempt to summarise those activities, why they’re important for journalists and publishers, and the key issues they raise for the way that we publish.

Watching and viewing are not the same thing

Watching and viewing is a good place to start. They may sound like the same thing, but in this categorisation they identify two very different ways of consuming video – whether that’s on television or online.

When watching, for example, they write:

“The news has your full attention and you do not want to be disrupted or be bothered by distractive talk in the same room.”

Viewing however:

“Refers to the subordination of the activity: news often functions as wallpaper for a main activity like preparing breakfast or dinner, checking your e-mail or reading the newspaper.”

The researchers note that more people now pause TV news – in the same way as they might put down a paper – to turn their attention to other activities before resuming. But also that they ‘schedule’ television for their own convenience, or watch it live on other devices, for example with work colleagues, in order to fit the structures of their lives.

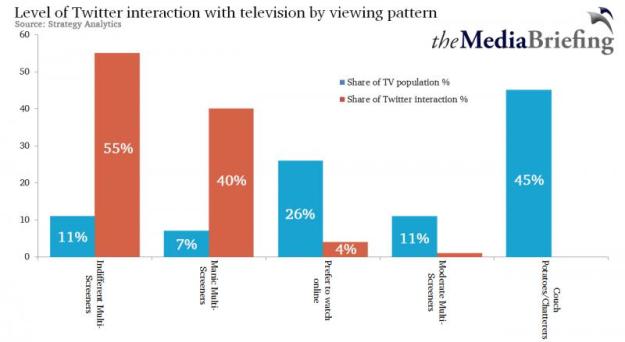

UPDATE (Sept 11 2014): Some very timely data reported by MediaBriefing claims that “only a third of television viewers are consuming the medium exclusively in the traditional, sole-focus-of-attention way”.

Reading is about depth; listening is barely remembered

Reading is used very specifically in the research to mean an activity which “is about depth: it is done individually, with great attention, and—when users have enough time—in longer sessions.”

Notably, it is not limited to print. One interviewee, for example, saves items to a “digital reading file” for moments when he can give them his full attention:

“Sometimes the items are a week old, but that doesn’t really matter, because in fact it is not quite about the really hard news, but about backgrounds.”

More broadly “reading as a particular practice of news use is less about knowing that something occurred than about understanding a news event” – other practices, such as ‘checking’, ‘scanning’ and ‘monitoring’ take up that role.

In contrast, listening is described as akin to viewing:

“Participants … often forgot to mention listening as part of their daily news use. They usually experience listening to news less as an activity in its own right than as part of a more general experience, like getting to sleep or driving a car. Although there are more active forms of listening to news, such as via podcasts, our participants seldom mention them.”

Bored or engaged? Checking and scanning vs snacking and monitoring

Perhaps the most interesting section of distinctions made by Meijer and Kormelink are those surrounding the different ways that people ‘check’ the news – with some encouraging findings for civic journalism and democratic participation.

Checking is:

“[A] habitual activity comparable to e-mail checking … A distinctive user pattern in this respect is what we have called a “checking cycle,” which involves checking the latest in terms of news, e-mail, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Tinder, Grindr, and so on, all in one quick session. The aim is to continuously stay on top of all that happens in your personal life and the world at large.

Snacking is more about gaining an overview: flicking through a newspaper, for example, is snacking. It is “a markedly more relaxed mode of news use than checking”.

Scanning, however, is more specifically geared towards the individual’s field of interest: their industry, for example, or sports team. It is socially or professionally functional, “enabl[ing] the user to take part in interactions about a particular news event”.

25-year-old Marjolijn, for example, says “She is less interested in the content than in the shared frame of reference it provides. Scanning allows for creating common ground with the relatives she is going to meet.”

Monitoring is where civic journalism comes in, however. And the section on this is worth quoting in more detail:

“Schudson (1998) once proposed that in order to function in a democracy, it might suffice for citizens to monitor the news instead of being fully informed. He made a striking comparison with parents watching their children in a swimming pool: they are keeping an eye out, prepared to come into action when needed.

“As a practice of news use, monitoring was not widespread in the Netherlands in the years 2004–2005. Our interviewees claimed to monitor the news only in the context of major calamities. Understandable, because it took some effort to keep an eye on events.

“Today, push messages, live blogs, social media like Twitter, and the “appification” of journalism and information have made monitoring extremely easy. People are actively invited to closely follow unfolding events that are important or appealing to them, whether it be the attacks in Oslo and Utøya (Thorsen 2013) or a fugitive “Bonnie and Clyde couple” on their way through the Netherlands and Germany.”

Searching or clicking?

Search is a major source of audiences for news organisations, and it is not surprising that the practice of searching is given its own category.

Searching here is about “finding an answer to a specific question”. Notably for publishers, however, “users attach less value to the gatekeeping abilities of news organizations, and prefer search engines and Wikipedia” although people do sometimes have “brand preference” for one news organisation over other results.

Clicking is the practice of consuming news via links – either to news articles or within news articles. It is compared to “choosing what to watch on TV or deciding which news to read in a newspaper”.

Notably, the practice of not clicking is also explored here, with the researchers arguing that it “does not automatically illustrate a lack of interest in news items.”:

“From the headlines or the lead, our interviewees generally derive sufficient information to get an impression or an update of serious events, as Marie-Claire (23) shows: “Technology [category] I always like, but usually the headlines are enough, unless I’m really like ‘Huh? How can that be?’” In other words, to click or not to click does not serve as a sound standard for the level of interest or importance attached to a news item.”

Indeed you could argue that this is actually the practice of scanning outlined above.

This is key to take into account when looking at site analytics: articles may not be getting traffic in terms of clicks while still being ‘read’ in terms of scanning on other pages and as a headline on social media platforms.

In these cases do publishers choose to change the headline, or reduce the articles to merely a headline? Perhaps linking to better coverage elsewhere. If there was ever a case for ‘Do what you do best and link to the rest‘, this may be it.

Linking, Sharing, Liking, Recommending, Commenting, Voting

Meijeira and Kormelink distinguish between various forms of distributing content, but explain that they all share an awareness of their public nature, which in turn influences what gets shared (bold not in original):

“Although social user practices such as linking (copying and pasting the URL of a news article), sharing (clicking on “share”), liking (clicking on “like”), recommending (clicking on “recommend”), commenting (leaving comments online) and voting (e.g., in response to a news poll) are quite distinct, the research participants appear to have similar considerations on whether or not to engage in these practices.

“As Rosa (26) indicated, she does not usually share, like, recommend or comment on news on Facebook because she “does not want to present herself too much on social media.” In this context, Picone (2011) argued that what keeps users from voting, sharing or reacting to a news story is not so much the difficulty of writing a comment, but the anticipated response of other users to it.”

In the conclusion the researchers again highlight that these behaviours are not limited to online news, partly due to privacy concerns:

“People still tend to share their news the way they did 10 years ago, offline (on the street, at the water cooler) and during moments (start of the workday, while walking the dog, etc.) where people are at a loss for a conversation topic. Instead of a rigid focus on “shares” and “likes,” it seems more useful to (continue to) monitor (new) communicative functions of news—also offline.”

‘Never read the news until I got a smartphone’

On the whole the research has some positive points to make about the internet’s impact on news consumption, noting in the conclusion 29-year-old Mark who “never paid attention to news until he got a smartphone in 2011”.

It points out that focused reading is not confined to any one medium, and that distracted forms of consumption popularly associated with smartphone use are equally typical of how people use television, radio or print. It’s not about the medium: it’s about the user.

“The value news has in people’s everyday life seems to hinge less on the increasing technological, social and participatory affordances of the informative platform than on time- and place-dependent user needs …

“News wants and needs, place, moment of the day and especially the convenience of a particular news carrier appear to be defining factors in what people do with news. As Rosa (26) explained, she checks the news on her smartphone and her work computer during the day, snacks the news on her laptop and in the newspaper after work, and reads her newspaper’s weekend supplements on Saturday morning at home.”

Perhaps most importantly, they urge a move away from current metrics of news consumption:

“The interests of news users may not be captured in clicks. For instance, checking, snacking and scanning do not necessitate a click. This means that journalists and journalism scholars would do well to part with clicking metrics as a sound standard for the level of interest or importance attached to a news item. In other words, to click or not to click does not automatically point to a news gap, nor to a need to alter the selection of news.”

Reblogged this on Dave Toomer.

That link is http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/21670811.2014.937149. Thanks for pointing the new study out to me!

Fascinating. Lots of journalistic food for thought there – especially about moving past clicking metrics as a measure of interest. Great survey.

Pingback: Around the Wire: Newspaper Reporters Turn to TV, 5 Tips for Hypnotic Writing and More Media News | Beyond Bylines

Pingback: Fascinating new Dutch research breaks down 16 levels of news engagement ::clicking is only one form:: | Newsplexer

Pingback: Fascinating new Dutch research breaks down 16 levels of news engagement ::clicking is only one form:: | Newsplexer

Pingback: Beyond the Wire » Worthy on the Web – September 19, 2014

Pingback: 16 reasons why this research will change how you look at news consumption - Rumble

Pingback: Social Media consumption and Management styles | dennisebelen

Pingback: What is this News You Speak Of? | twalker67

Pingback: Newsletter Farol Jornalismo #11 Guardian membership, plataforma de publicação Know e o jornalismo feito por robôs | Farol Jornalismo

Pingback: Beyond the Wire » Worthy on the Web – Best of 2014

Pingback: What you read most on the Online Journalism Blog in 2014 | Online Journalism Blog

Pingback: 16 Arten News zu konsumieren – multimedial

Pingback: Metrics and the media: we can measure it – but can we manage it? | Online Journalism Blog

Pingback: Auswege aus der Klickfalle « Die MEDIENWOCHE – Das digitale Medienmagazin

Pingback: 16 reasons why this research will change how you look at news consumption - Digitalchef

Pingback: Hard and Soft News – KATHRYN KELLY PROFESSIONAL COMMUNICATIONS