Monsters dwell in the hinterlands of the known world, symbolic expressions of cultural unease. Inhabitants of an imagined realm adjunct to the everyday, monsters offer powerful tropes and tools for learning and teaching in the arts and humanities

Introduction

The Higher Education Academy is running a conference called ‘Heroes and monsters: extraordinary tales of learning and teaching in the arts and humanities’ . I have been invited to run a workshop on the psychology of open education ‘You cannot be half-open: On wrestling your inner MOOC’. I want to focus on the inner barriers academics wanting to operate in the open web encounter and how they can overcome them. This is what I am defining as the psychology of open education and I have decided that my next book will be about this. I do not mean to patronise those who know, but some people new to open education are reading this post and may not know about MOOC monsters, here is a good start. There are numerous references to MOOC monsters and even some sound academic dialogue. What follows are my notes for the conference session.

I have come to believe that the success of open education may rest on our ability to support new adopters in wrestling these inner monsters and find spaces to tell epic stories about inner battles with open sharing. Without this inner viewing, interest and learning about infotention and other digital literacies may be tactical but not sustainable. I am not alone in this belief. Jim Groom was quoted as saying recently:

You don’t need new technology to change your teaching… you need a new you.

The assertion in the workshop title ‘you cannot be half open’ is purposefully challenging and describes the position I have arrived to after 3 years of inquiring into my own practice as I move towards open sharing and full creative commons licensing of my work. The half-open option, I now see as a skilful transition state. For me, the half open option is not sustainable without too much inner turmoil. I am now an independent researcher and educator, working only as a consultant to universities and corporations. This has given me the freedom to show my work, ideas, and workings online without compromises. I am saddened by the lack of interest the universities I am associated with have shown in my 3 year experiment – but this is not my monster to wrestle. What a relief to have come to this conclusion early (…ish) in life.

The dynamics of open sharing are complex at the individual and at the organisational level, trying to untangle the agendas and get clarity is not straight forward. I leave it to others more knowledgeable than I to deal with the procedural, political and technological challenges of open online education – my focus is on the individual and how their psyche may or may not be ready to live and learn on the open web.

Alan Levine tells us that ‘there is a difference between being on the web and being of the web’. The half way option left me feeling like I was attempting to be on the web but lacking in understanding about what it meant to be ‘of the web’. Three years on, I am clearer about the end I aspire to, but I still wrestle with fear daily. I am a work-in-progress open educator.

I believe now, but did not 3 years ago, that to see the potential of digital scholarship we need to experience connected learning on the open web. Academic institutions that do not support their academics in this endeavour will not, in my view, be able to learn about the potential of truly open sharing. Until I was free to take the risk to learn in the open, I did not see the potential. Some things do have to be experienced to be believed.

A journey into our inner fears

The journey to open sharing is a developmental journey that aligns well with my life as a buddhist contemplative. The study of the 3 characteristics of experience in buddhism – impermanence, dissatisfaction and not-self – have given me useful practices to work with as an open educator online. The intersection between technology, meditation and life is the focus of my work now with the creation of a digital contemplation studio to support the attention literacies that are needed to make mindful infotention work online. Howard Rheingold focusses more on the tools and filters we need to amplify mind online, but clearly states the need to train the mind to attend.

Honing the mental ability to deploy the form of attention appropriate for each moment is an essential internal skill for people who want to find, direct, and manage streams of relevant information by using online media knowledgeably.

The digital contemplation studio will be a website to practice this internal skill of deploying the attention, thus supporting the development of contemplative mind in society. I see the discipline of attention training as a prerequisite to working with psychological barriers to living and learning fully in the open as well as for using online media knowledgeably. We humans are just not as smart as we think we are, and our ability to self-assess what may be colouring how we share online is pretty limited.

Source:http://img46.imageshack.us/img46/6424/damned.jpg

Source:http://img46.imageshack.us/img46/6424/damned.jpg

We are scared of idling in the uncertainty of ‘public’, scared of looking in the mirror when hooked by some written text on a screen. Yet, also worried that we are missing out on the potential of the web, we are in a double bind. Creating blended options, new pedagogies, and arguing about whether MOOCs should be x or c or just modern seem useful displacement activities. I choose to focus instead on tackling the inner barriers that make us see the situation as we are rather than as it is. A daily attention practice has given humility and provisionality to views I hold as given – without a trained attention, monsters just wrestle underground.

Yet sometimes these fears are adaptive. Relinquishing privacy on the web can bring both delight and sorrow – by definition we no longer control who has access to the work we share. In this sense, it becomes an ideological more than a pedagogical decision to embark on the road to open. The reality of our inner lives, as we consider the risks, often looks like what Caroline Paul depicts here:

There is technology, pedagogy, copyright law, political stances, and our own psychology. The situation is messy, complicated and resists simplification. There are no top ten tips to offer sadly. We can engage in skilful dialogue with those wanting to wrestle certain common inner MOOC Monsters: making our workings public, relinquishing privacy, and generally being scared of the vulnerability entailed in opening our inner lives to anyone on the web. It is a pretty big ask and the cost can be high, let’s state that upfront. Hence,

Sharing stories at the hellmouth

creative commons licensed ( BY-SA ) flickr photo shared by cogdogblog

I set out late 2011 to carry out an educational experiment to ‘transfer my teaching online’. I saw it as ‘transfer’. I felt I needed to learn how to teach online and then just transfer my courses to the right learning management system (LMS). It never occurred to me that my university would be anything but excited by the idea and what I was learning. I wanted to learn online if I was to teach online to evaluate best practice and change my own. This starting point seems a lifetime ago. In April 2014, I met face to face for the first time the man responsible for opening the door to open education – Martin Weller. Let me outline some of the stopping points to this photo.

The online educational experiment started with Lettol, via Getting to grips with Moodle and this led me H817 at the Open University all of these were qualifications in password protected LMSs. I found the whole LMS experience unsatisfactory. The potential I could see was not fulfilled by them. I discovered that there was such a thing as open online education when I did my first MOOC: Martin Weller’s cMOOC #H817open. It was overwhelming at first, and I ran to the comfort of the walled garden at the LMS at the Open University. But not for long. Open education in the form of 10 days of Twitter, Twitter Vs Zombies, Introduction to openness in education pulled me in and taught me over time to overcome my fears. I have also now attended a few xMOOCs – mainly with edX in my own academic discipline to enable meaningful comparisons with the truly open online experience. Some current online experiences (the distinction between teaching and learning is much fuzzier in the open web) to add to this list are: Rhizomatic Learning, Technology Enhanced learning, and coming up soon Thoughtvectors : ‘Living the Dreams’. To reflect on all this I helped set up a community on Google Plus called Meta-MOOC to share learning on all our online experiences. There is a wealth of support for open learning out there and I am privileged to feel part of this network.

This particular conference attracted my attention because its theme ‘Heroes and Monsters’ described in a stark way how it has felt to engage in the challenge of becoming an open educator. I have felt like one of those unsung heroes mentioned in the call for papers ‘who hold the line at the hell-mouth by sharing tales of epic battles and vanquished learning and teaching demons’ whilst nobody in my physical life network cared to listen.

I found a ‘home’ online with a poster child of open online Education: DS106 – the Digital Storytelling course run as a MOOC hybrid both open and onsite at the University of Mary Washington. I completed it last year as an open participant and I have stayed as part of this community that has taught me so much about open sharing. I have also been a participant, am now a part of the #phonar network (an open online undergraduate photography class) and look forward to learn with and mentor young people in the upcoming Phonar Nation being run by Jonathan Worth – a youth photography class.

It feels fitting that I report on the results of this 3 year educational experiment at a heroes and monsters conference. I have, after all, learnt that ‘Twitter and Zombies’ is more than an online game…but that is another story. The road to a little less ignorance has been full and long – may some of what I have learnt be of use to others.

Barriers to open

What are the perceived barriers to open academics in particular raise? Alan Levine offers this slide as an exploration into this question:

Alan talks about the ‘reluctance to be open’. He refers to the barriers most of us state to living and learning in the open web as the ‘shut down of sharing language’ and that it is this language that keep us from building ‘a common information space in which we communicate by sharing information’. I recommend you read his post. He seems to have overcome his inner monsters and be comfortable being of the web. I find his approach helps me see what is possible as I wrestle with my own reluctance. I commented on his blog post:

The reluctance you mention is definitely there and making changes is about changing deep psychological patterns as much as about learning the technology and changing an educational system that rewards academics for individual ownership rather than open sharing. It is complicated. Your stories of open are a huge contribution to this domain – if we can point to these when trying to convince colleagues to engage, at least they cannot say ‘it can never happen’. It becomes clear, that it is not happening for them or their organisation because of their fears – but it is happening for those who are willing to live with the uncertainty of open. Once again the joy you find on ‘da web’ comes through in each word. It is really heartening to read.

Your weapons of choice

Role models and sounding boards

So here is the first strategy to wrestling your inner monsters, find role models that you can learn from – people who get and live the value of ‘a common information space in which we communicate by sharing information’. No rhetoric, no labels, just human beings using a tool to share with each other. In my experience of proprietary LMS online courses, xMOOCs and cMOOCs and NOT_A_MOOC I have found that the difference that made the difference to engagement and learning for me personally could be summed up with the construct of educational presence:

Presence is defined as a state of alert awareness, receptivity, and connectedness to the mental, emotional, and physical workings of both the individual and the group in the context of their learning enviroments, and the ability to respond with a considered and compassionate best next step.

Mass mailings, unresponsive or absent professors, mindless quizzes, are not the essence of educational presence. Alan Levine often talks about the need students and all human beings have ‘just to be seen’. In his many years of being of the web, I take it he knows this domain and I see him and others like him as role models and sounding boards to help me navigate the murky waters of composing a further life online.

I know I will not be composing any emails like the one below. Taken from one of the xMOOCs I attended and de-registered from.

We are human: it’s complicated

For each simple communication we exchange online, we are not only dealing with the technology or social media platform but with a complex human being. Virginia Satir’s model of the iceberg in communication has been copied and adapted many times. It highlights the level of complexity that is at play within each individual and that (as we rarely have access to anything more than written text online) we may easily miss as we send tweets back and forth.

We each are much more than 140 characters and, as James Hillman said, it pays to treat each thing ‘as if it were alive’. I might paraphrase this as ‘treat each comment or tweet you read as coming from a ‘thing’ that is alive and wants to be seen for more than the transactional usefulness they may have in the context of your PLN (personal or professional learning network)’ – but not as catchy, I know. We all have yearnings, expectations feelings and blind spots. Each day I learn that technology mediated communication is as good a developmental tool as any psychotherapist couch, reflecting back to us in a non-judgmental manner our own psychological patterns. We rarely stop for long enough to see them, but that is another issue.

We each are much more than 140 characters and, as James Hillman said, it pays to treat each thing ‘as if it were alive’. I might paraphrase this as ‘treat each comment or tweet you read as coming from a ‘thing’ that is alive and wants to be seen for more than the transactional usefulness they may have in the context of your PLN (personal or professional learning network)’ – but not as catchy, I know. We all have yearnings, expectations feelings and blind spots. Each day I learn that technology mediated communication is as good a developmental tool as any psychotherapist couch, reflecting back to us in a non-judgmental manner our own psychological patterns. We rarely stop for long enough to see them, but that is another issue.

Basic human needs matter

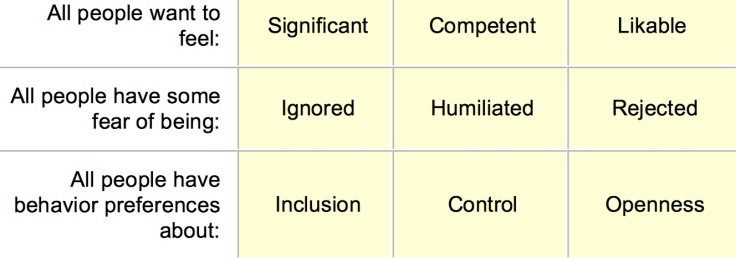

A summary of basic human needs as seen by the FIRO theory of interpersonal relations:

As you look at this table your personal preferences in each cell are likely to be different from those you interact with online. Unfortunately we tend to assume just the opposite, that those we interact with are ‘just like us’.

As you look at this table your personal preferences in each cell are likely to be different from those you interact with online. Unfortunately we tend to assume just the opposite, that those we interact with are ‘just like us’.

People who have high need for inclusion for example, are likely to more easily fall victim to FoMO than those who score low here. A high need for control is not likely to go hand in hand with comfort with the unpredictability of online life. In an obvious way, scoring low on openness is going to make it hard to engage in an open learning forum and talk to strangers about our struggles. I find this approach to human understanding powerful and it can help us overcome fear with practice and awareness of our basic human needs. I can offer a fuller treatment of this on another post, if it would be of interest. Just leave a comment.

When we are learning to live and learn in the open web we are taking information from our inner lives, from the online environment and making sense of what we see using theoretical frameworks we know and our own history (both personal and professional). As well as this conscious process, there are all the unconscious ones that play out as we engage. For example, as we work to join an online learning community we may be producing outputs that we know are valued within it just to get approval. This will have a significant impact on how comfortable we may feel in the situation, but we are unlikely to be aware of this pattern playing out.

Pay attention to attention

This brings us back to the need for training attention. Our attention can be focussed on different realms of experience: the online external world, our sensed behaviours and feelings, our thinking patterns, or the meta-cognitive realm where we can attend to the whole not the parts. There are different types of attention as well as different realms to attend to and buddhist psychology has the most to offer us here as we talk about tackling our inner monsters. I highly recommend the study of the Attention Revolution by Alan Wallace. It humbled me into seeing that just to gain the ability to open the doors to trustworthy self-assessment requires years of practice. Or as Artemus Ward so aptly put it;

‘It ain’t so much the things we don’t know that get us into trouble. It is the things we know that just ain’t so’.

We think we can control what we attend to, the reality is that, without training, sustained voluntary attention on any object stands at a measly 300ms if we are lucky. In essence this means that we are unlikely to have much insight into what motivates our behaviour or the capacity to change unless we develop our ability to attend.

Our words as a way into the unconscious

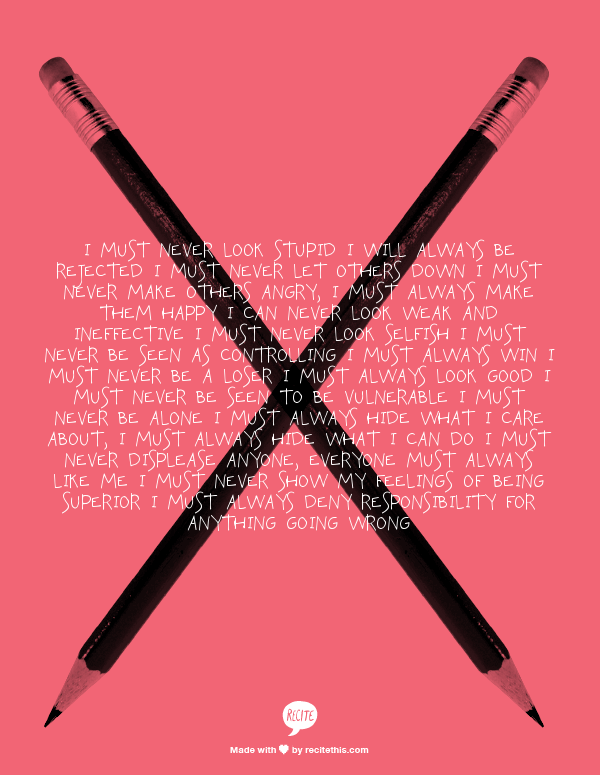

Our use of language can give us a useful way into insight. You might, for example, look at turning your rigid rules (see poster above if you need inspiration to connect to the fears you share with the rest of all of us humans) into more flexible guides for action. Virginia Satir used this approach. It hinges around taking time to reflect about your inner life through asking certain questions:

- Write down key barriers that stop you from engaging with open education in the form of: I must always, I must never, I should always : “I must always get it right’ ‘ I must never ask for help’ ‘I must never risk being seen as not in control’.

- Work out what the catastrophic expectation is for each barrier. Ask yourself: What would happen if i do/don’t? ‘If I get it wrong, then I’ll look stupid and be rejected; if I am rejected, I will die”. Please be clear that we are not talking to your logical but to your emotional self here. Fundamental fears like these, always come back to being ignored, humiliated, rejected and some say that all fear can be boiled down the fear that we will die.

- Start to transform the rules. Let’s take an example “I must never get it wrong” can transform to “I can never get it wrong”

- And again. “I can sometimes get it wrong”

- And finally “I can get it wrong when: I don’t know the answer, I am with people I trust, I want to show my students to engage with uncertainty.”

- Do this again, and again and again when you notice a rule that gets in the way of you making a positive choice work openly.

These fears/barriers/rules will keep popping up. They pop up at the places where you feel the temptation to blame, placate, dissociate, or generally feel uncomfortable. Instead of externalising the fear, bring it in and engage with what psychologists call desirable difficulties when learning – lean into what you would rather avoid for long term learning. Listen deeply to the fear that is at play and work with it. Turn it into a flexible guide to action. This will take you from ‘compulsion to choice’ . Read Virginia Satir’s book to learn more about this. This short video shows you an example:

Weave multiple qualities of attention into your written speech

You can inquire into your inner fears by being purposeful about your online communication . Take time to structure your communications in such a way that all the realms of experience are represented. Particularly, when you start blogging or start posting comments. Use your engagement as a reflective practice. What would it mean for you to express yourself in a balanced way?

- Inquire into others’ perspectives and views

- Advocate your view and own it as yours

- Illustrate your points with examples and stories

- Frame your writing – purpose, intention, how you hope your words will serve the whole

Read more about interweaving multiple qualities of attention in written or spoken speech in the work of Bill Torbert. Online you can review your conversations and learn about your biases. We have personal preferences and will often overuse particular speech patterns, such as too much advocacy which may not always find an echo in a given community or too much inquiry leaving those we interact with unclear about our own voice.

Find or create a back channel to connect in depth

@francesbell @mdvfunes @nickkearney should be an Internet Rule. Rule 107: There is *always* a backchannel. You’re just not always on it.

— David Kernohan (@dkernohan) February 14, 2014

Thank you to Frances Bell for reminding me of this wonderful exchange in the comments below. I wrote back:

I was mindful that I did not explore the relationships that build offline as we get to know each other online – forgive me, but I do not like ‘back channel’ as an expression as it removes agency – I do need to speak more about that. For those starting out on the road to open, it may appear that the public online interactions are all there is. As you rightly mention, much goes on to build relationship that is not seen and uses more private channels such as video chat, email, google doc chatting, shared wikis, collaborative blogging sites, direct messaging on Twitter,etc. Humans find a way through the tools to get to know one another! This is the one thing that keeps me hopeful about open education.

It may seem obvious but it was not obvious to me when I started. The online experience starts a process that is developed by us in the same way as we develop any relationship. As we get to know one another, collaborative projects evolve and friendship can grow. Jenny Mackness says in the comments below:

The back channel has been hugely influential in my learning. Off the top of my head, I think of ‘open’ as being the breadth and the back channel as the depth, in other words I need the openness of others to fuel the ‘back-channel’.

So, an easy way of wrestling fears is to have that depth and that back channel available as it will often give you support to cope with difficulty, advise in new situations, and a great set of friends and colleagues to work with beyond your physical location. This may be the essence of what it means to learn to be of the web and not just on it!

In conclusion

Work at your own pace, do not let anyone force you into openness online faster than you are ready for it. Susan Cain’s excellent practical tips to overcoming your fear of ‘putting yourself out there’ is a great place to learn more. If you want practical help on developing an academic presence online this post on how to ‘stop being an academic hermit’ might help.

Ultimately in becoming an open educator your are making a choice to relinquish some of your privacy and control of where your work goes in order to share it with others. Hopefully, as a result, you will have the structured serendipity of the web offer up amazing stories of open sharing. Yet, this is not self-evidently a good thing, it is a choice we make if we believe in the potential this ‘common information space in which we communicate by sharing information’ has for educating people. May be the earth is the biggest MOOC, and some of us feel optimistic about how the internet can enhance our connection. We can use it to learn, we can use it to augment and amplify our cognition or not. The future is up to us.

Facing inner fears gives us greater choice to be part of something larger than just the self or just the institution. You may well find yourself telling Alan Levine your story of open sharing in no time!

Resource update

You can find a summary audio of the talk on Tumblr.

You can find Alan Levine’s audio on being of the web not on the web on Soundcloud.

You can find Jim Groom’s audio about needing a new you to change your teaching on Soundcloud.

Slides I used were mainly the animated gifs and video already in this post, so I have not uploaded the deck. I did create some quick video notes with the slides and commentary and uploaded to You Tube.

May 30, 2014 at 7:16 pm

Thanks Mariana for that explanation. I have been understanding open as ‘a state of mind’ to quote Martin Weller and his work on open scholarship. But I first started thinking about the meaning of open after CCK08, when we published our Ideals and Reality of Participating a MOOC paper – http://www.lancaster.ac.uk/fss/organisations/netlc/past/nlc2010/abstracts/Mackness.html – and then later with Carmen Tschofen, when we published our Connectivism and Dimensions of Individual Experience paper – http://www.irrodl.org/index.php/irrodl/article/view/1143. So for me it has not been so much about location or copyright as about what effect it has on my identity. Hope this makes sense 🙂

June 1, 2014 at 4:13 pm

I think of it as a state of mind, for me it is a state of mind that is not supported by default closed settings as explained by Dave Coplin and to my mind most academic institutions have the closed default setting he describes. The situation the individual is in has to be considered when trying to explain his/her behaviour. I was drained and exhausted by having to find ways around the rules to do what made sense when I was in that system. This is what half-open meant to me -exhaustion. Open Education has given me a chance to meet wonderful people like you who, as you show in your comment, have been pioneers in this domain and we can learn, teach and research together. Much of what I can just chose to do now, would have had to have been negotiated in the past. The freedom of that has absolutely impacted on my identity, but for me issues of copyright have been central to that. In fact, I see this journey as having a clear endpoint: CC0 for all my work. To me this encapsulates the potential of this web of ours. Identity becomes secondary to being in service of a larger whole. This is the ideal, of course. The reality is that many demons have to be wrestled with before the ideal could obtain if ever. Thank you for taking the time to talk and help me explore these ideas. I am very a WIP open educator, thankful to be learning from the best 🙂 I will read the links you point me too.

May 30, 2014 at 6:31 pm

The back channel has been hugely influential in my learning. Off the top of my head, I think of ‘open’ as being the breadth and the back channel as the depth, in other words I need the openness of others (I’m not that good at openness myself – see http://jennymackness.wordpress.com/2013/05/18/open-academic-practice-how-open-are-you/) to fuel the ‘back-channel’. I feel much more comfortable in the back-channel. So – I’m afraid I probably am an example of ‘half open’! I am prepared to share quite a lot – blog, publish in open journals, allow use of my Flickr photos and so on, but not to bare my soul in public and definitely not to expose my family and close friends!

May 30, 2014 at 6:52 pm

🙂 Hello, Jenny. On reading your response I am struck by the half open comment. May be I need to review the post to explain that when I say half open I am not thinking about ‘level or extent to which one discloses’. Half- open to me is more about the ‘on the web versus of the web distinction’. I perceive you as of the web, you work within it and use its unique affordances. My experience with working online behind a registration wall (or walled garden as the OU called it) is the reference experience I have for the ‘half open’ option. Working on the open web offers us all the choices you mention, and also offers us choice about the extent to which we choose to share and what aspects of our life we bring out in the open. I think the thing that helped me the most, was the respect I felt from the word go in the DS106 community for my own need to manage the extent of open sharing. I still manage my choices each day. Choices I cannot make behind a registration wall. For that I am grateful. I might have stayed making/taking Moodle courses and never found out what else was possible. Nothing wrong with Moodle, but the open web is so much more… Thanks for stopping by, and helping me frame my thinking for next week a little more.

May 28, 2014 at 11:09 am

(correction) .. that should have been “to help them (if they weren’t already) become knowing, ethical, effective actors on the web”

May 28, 2014 at 9:46 am

I now realise that I spent a lot of energy ‘bringing the web into campus-based education’ – great term! One the responsibilities I assumed in latter years was very concerned with student agency on the web – to help them (if they weren’t already) by knowing, ethical, effective actors on the web, as opposed to passive consumers whose consumption generates ‘content’ and data for the Googles and Facebooks of the world.

Do invite me to your backchannel exploration – sounds exciting.