How the Professor Who Fooled Wikipedia Got Caught by Reddit

T. Mills Kelly encourages his students to deceive thousands of people on the Web. This has angered many, but the experiment helps reveal the shifting nature of the truth on the Internet.

A woman opens an old steamer trunk and discovers tantalizing clues that a long-dead relative may actually have been a serial killer, stalking the streets of New York in the closing years of the nineteenth century. A beer enthusiast is presented by his neighbor with the original recipe for Brown's Ale, salvaged decades before from the wreckage of the old brewery--the very building where the Star-Spangled Banner was sewn in 1813. A student buys a sandwich called the Last American Pirate and unearths the long-forgotten tale of Edward Owens, who terrorized the Chesapeake Bay in the 1870s.

These stories have two things in common. They are all tailor-made for viral success on the internet. And they are all lies.

Each tale was carefully fabricated by undergraduates at George Mason University who were enrolled in T. Mills Kelly's course, Lying About the Past. Their escapades not only went unpunished, they were actually encouraged by their professor. Four years ago, students created a Wikipedia page detailing the exploits of Edward Owens, successfully fooling Wikipedia's community of editors. This year, though, one group of students made the mistake of launching their hoax on Reddit. What they learned in the process provides a valuable lesson for anyone who turns to the Internet for information.

The first time Kelly taught the course, in 2008, his students confected the life of Edward Owens, mixing together actual lives and events with brazen fabrications. They created YouTube videos, interviewed experts, scanned and transcribed primary documents, and built a Wikipedia page to honor Owens' memory. The romantic tale of a pirate plying his trade in the Chesapeake struck a chord, and quickly landed on USA Today's pop culture blog. When Kelly announced the hoax at the end of the semester, some were amused, applauding his pedagogical innovations. Many others were livid.

Critics decried the creation of a fake Wikipedia page as digital vandalism. "Things like that really, really, really annoy me," fumed founder Jimmy Wales, comparing it to dumping trash in the streets to test the willingness of a community to keep it clean. But the indignation may, in part, have been compounded by the weaknesses the project exposed. Wikipedia operates on a presumption of good will. Determined contributors, from public relations firms to activists to pranksters, often exploit that, inserting information they would like displayed. The sprawling scale of Wikipedia, with nearly four million English-language entries, ensures that even if overall quality remains high, many such efforts will prove successful.

Last January, as he prepared to offer the class again, Kelly put the Internet on notice. He posted his syllabus and announced that his new, larger class was likely to create two separate hoaxes. He told members of the public to "consider yourself warned--twice."

This time, the class decided not to create false Wikipedia entries. Instead, it used a slightly more insidious stratagem, creating or expanding Wikipedia articles on a strictly factual basis, and then using their own websites to stitch together these truthful claims into elaborate hoaxes.

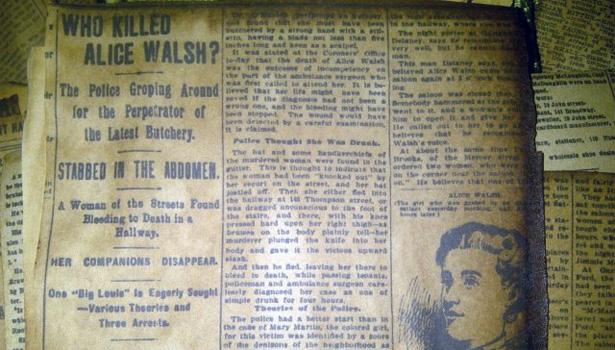

The second group settled on the story of serial killer Joe Scafe. Using newspaper databases, they identified four actual women murdered in New York City from 1895 to 1897, victims of broadly similar crimes. They created Wikipedia articles for the victims, carefully following the rules of the site. They concocted an elaborate story of discovery, and fabricated images of the trunk's contents. Then, the class prepared to spring its surprise on an unsuspecting world. A student posing as Lisa Quinn logged into Reddit, the popular social news website, and posed an eye-catching question: "Opinions please, Reddit. Do you think my 'Uncle' Joe was just weird or possibly a serial killer?"

The post quickly gained an audience. Redditors dug up the victims' Wikipedia articles, one of which recorded contemporary newspaper speculation that the murderer was the same man who had gone on a killing spree through London. "The day reddit caught Jack the Ripper," a redditor exulted. "I want to see these cases busted wide open!" wrote another. "Yeah! Take that, Digg!" wrote a third.

But it took just twenty-six minutes for a redditor to call foul, noting the Wikipedia entries' recent vintage. Others were quick to pile on, deconstructing the entire tale. The faded newspaper pages looked artificially aged. The Wikipedia articles had been posted and edited by a small group of new users. Finding documents in an old steamer trunk sounded too convenient. And why had Lisa been savvy enough to ask Reddit, but not enough to Google the names and find the Wikipedia entries on her own? The hoax took months to plan but just minutes to fail.

Why did the hoaxes succeed in 2008 and not in 2012? If thousands of Internet users can be persuaded that Abraham Lincoln invented Facebook, surely the potential for viral hoaxes remains undiminished.

One answer lies in the structure of the Internet's various communities. Wikipedia has a weak community, but centralizes the exchange of information. It has a small number of extremely active editors, but participation is declining, and most users feel little ownership of the content. And although everyone views the same information, edits take place on a separate page, and discussions of reliability on another, insulating ordinary users from any doubts that might be expressed. Facebook, where the Lincoln hoax took flight, has strong communities but decentralizes the exchange of information. Friends are quite likely to share content and to correct mistakes, but those corrections won't reach other users sharing or viewing the same content. Reddit, by contrast, builds its strong community around the centralized exchange of information. Discussion isn't a separate activity but the sine qua non of the site. When one user voiced doubts, others saw the comment and quickly piled on.

But another, more compelling answer, has to do with trust. Kelly's students, like all good con artists, built their stories out of small, compelling details to give them a veneer of veracity. Ultimately, though, they aimed to succeed less by assembling convincing stories than by exploiting the trust of their marks, inducing them to lower their guard. Most of us assess arguments, at least initially, by assessing those who make them. Kelly's students built blogs with strong first-person voices, and hit back hard at skeptics. Those inclined to doubt the stories were forced to doubt their authors. They inserted articles into Wikipedia, trading on the credibility of that site. And they aimed at very specific communities: the "beer lovers of Baltimore" and Reddit.

That was where things went awry. If the beer lovers of Baltimore form a cohesive community, the class failed to reach it. And although most communities treat their members with gentle regard, Reddit prides itself on winnowing the wheat from the chaff. It relies on the collective judgment of its members, who click on arrows next to contributions, elevating insightful or interesting content, and demoting less worthy contributions. Even Mills says he was impressed by the way in which redditors "marshaled their collective bits of expert knowledge to arrive at a conclusion that was largely correct." It's tough to con Reddit.

The loose thread, of course, was the Wikipedia articles. The redditors didn't initially clue in on their content, or identify any errors; they focused on their recent vintage. The whole thing started to look as if someone was trying too hard to garner attention. Kelly's class used the imaginary Lisa Quinn to put a believable face on their fabrications. When Quinn herself started to seem suspicious, it didn't take long for the whole con to unravel.

If there's a simple lesson in all of this, it's that hoaxes tend to thrive in communities which exhibit high levels of trust. But on the Internet, where identities are malleable and uncertain, we all might be well advised to err on the side of skepticism.

Sometimes even an apparent failure can mask an underlying success. The students may have failed to pull off a spectacular hoax, but they surely learned a tremendous amount in the process. "Why would I design a course," Kelly asks on his syllabus, "that is both a study of historical hoaxes and then has the specific aim of promoting a lie (or two) about the past?" Kelly explains that he hopes to mold his students into "much better consumers of historical information," and at the same time, "to lighten up a little" in contrast to "overly stuffy" approaches to the subject. He defends his creative approach to teaching the mechanics of the historian's craft, and plans to convert the class from an experimental course into a regular offering.

There's also an interesting coda to this convoluted tale. The group researching Brown's Brewery discovered that the placard in front of the Star-Spangled Banner at the National Museum of American History lists an anachronistic name for the building in which it was sewn. They have written to the museum to correct the mistake. For those students, at least, falsifying the historical record may prove less rewarding than setting it straight.