Abstract

Education is considered to be the most effective tool that people can use to lift themselves out of poor socioeconomic backgrounds and lead to professional success, which in turn improves society. Since an education system often supports individuals with a higher socioeconomic status (SES), it may not resolve the issue of socioeconomic background impacting on career outcomes. Given the nature of the research questions, an individualistic approach is used for selecting tools. Using qualitative and quantitative analysis methods, we argue that graduates studying an 8-year engineering program fail to succeed compared to counterparts who studied a 4-year engineering program. Findings suggest that engineering graduates’ socioeconomic backgrounds help them with their career advancement. A policy intervention may help to address the influence of SES on engineering education and professional employment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Higher education especially professional provision and the job market should ideally be well integrated (Trace, 2015). Despite this belief, higher education and work may also sometimes be very different from each other because some parameters (such as country context, field of study, source of education finance, employment pattern, and eras) will dictate the development of such a heterogeneous relationship (Alam, 2021). Marginson (2019) argued that a heterogeneous higher education sector may fail to meet the ‘realism test’ as it uses a simple way of solving a complex problem. When socioeconomic status (SES) plays a significant role in defining ‘income drivers’ (Goodman, 2014; Zhao, 2012), education may fail to provide the desired outcome. Under such circumstances, SES can also be one of the key agents that supports individuals’ success in higher education and career advancement. This study thus aims to examine whether education helps graduates to succeed in furthering their higher education and professional objectives by overcoming the influence of SES.

SES is defined by an individual’’s, family’s, or community’s position compared to other groups in a neighbourhood or the wider society (Conger & Donnellan, 2007; Green, 1970). Although this definition varies widely from country to country, SES is represented by an index of social, economic, and cultural variables that initially developed following a large-scale assessment by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and Programme for International Students Assessment. This index primarily comprises parents’ education status, family wealth, education resources and practices in the home, and family culture.

Research problem, objectives, questions, and scope

The relationship between education and SES is reciprocally symbiotic (Kincaid & Sullivan, 2017). For example, while education often increases individuals’ incomes, it also improves their social and economic status. Conversely, students from a privileged background can more easily access a quality education. Since the publication of the Coleman Report,Footnote 1 many studies have documented SES’’s effect on academic achievements; however, it varies across different socioeconomic contexts (Liu et al., 2020). For example, Conger et al. (2002) argued that family hardship could be detrimental to parental emotions or perceptions, practices, and behaviours, thereby affecting their children’s education. Parental education may also impact on their children’s academic achievements.

When a higher SES ideally offers an incentive in education for one or more privileged groups, it may generally exacerbate inequalities. In contrast, Alam (2021) argued that education improves individuals’ capital levels and that may also ideally support removing the socioeconomic disadvantages in many cases. Since education increases income and social status, individuals with more years of schooling are more likely to offset poor SES’’s impact on their subsequent professional education (Conger & Donnellan, 2007). In this study, we firstly examine whether socioeconomic status affects the academic attainments and which subsequently influence the students’ success in further education. Hence, we consider the grade points average (GPA) as a measure of academic success. Secondly, we examine whether the SES’s effect on academic attainments influences the success attained in a professional career. Thirdly and finally, we attempt to explore a way forward that can help to offset the impact of SES in achieving academic and professional objectives particularly for engineers. To examine these issues, this paper considers Bangladesh as a case study.

In examining whether the graduates who have achieved university degrees by spending a relatively longer period in a particular education program have managed to offset the effect of SES, we consider graduates as a sample from two engineering universities. One of them is BUET (Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology) and the other is DUET (Dhaka University of Engineering and Technology). Students of DUET already have a 4-year diploma engineering (DE) degree before enrolling in the engineering program at the bachelor level. On the other hand, students of BUET do not have prior engineering qualifications but have a 2-year Higher Secondary Certificate (HSC) before enrolling at the same level. The HSC graduates mostly came from a privileged SES (Alam, 2021; Alam et al., 2014). This means that DUET graduates with a lower SES have spent relatively more time in relevant education programs to be engineers.

Comparing the graduates who have undergraduate engineering degrees from these two universities, this study explores how socioeconomic status dominates engineering graduates’ further academic and professional successes, regardless of how long graduates spent being educated. Whether B.Sc. engineers graduating from these two universitiesFootnote 2 receive the equivalent opportunity in jobs is examined so that professional success can be measured. The above discussion briefly explains the central focus and context of this research. Hence, the objectives of this research are to firstly, analyse the impact of SES on the success of graduates’ elementary stage of education; and secondly, explore the subsequent effect of this situation on further education and career advancement. In the process of accomplishing these objectives, this research intends to answer the following three research questions:

-

Does SES influence the attainments or outcomes of engineering education?

-

Are these attainments vital for career advancement?

-

How can an engineering program help to offset the influence of SES?

While the first and second research questions are aligned with the research problem that has been outlined, the third attempts to address the constraints generated.

This study contributes in the following two ways. Firstly, unlike previous studies, we argue students associated with lower SES but with a prior engineering education achieve less academic success than their higher SES counterparts. Most studies have argued how socioeconomic status affects academic achievement, considering that both groups have the same education background and their study program lasted for the same amount of time. To the best of our knowledge, none has examined whether a stipulated period for an academic program in the same discipline is more important than SES in achieving successful study outcomes and professional careers. Secondly, using a causal analysis, this study finds that students with a lower socioeconomic status and prior engineering backgrounds in the same discipline do not succeed in subsequent programs and professional careers, compared to their higher SES counterparts who have no previous engineering background. Findings strongly suggest that students from poorer socioeconomic backgrounds require special attention to achieve as much as they can in education.

The following sections describe the research context and conceptual framework, followed by a description of the methodology and data. Then, descriptive statistics and empirical results are presented, and this paper ends with a discussion and concluding remarks.

The research context: engineering education in Bangladesh

During the British colonial period, Ahsanullah School of Engineering (ASE) was the foremost institute established in the Bengal region, and its purpose was to produce graduates in engineering disciplines. Later it was converted into a polytechnic (Chowdhury & Sarkar, 2018) and then into an engineering university with the name East Pakistan University of Engineering and Technology. Following independence in 1971, it was again retitled Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology (BUET). Becoming a university meant changing its rules and regulations. For example, polytechnic graduates known as diploma engineers (DE) are not currently eligible for higher education in BUET (Alam & Forhad, 2021b). BUET and its affiliated or similar institutions like the Bangladesh Institute of Technology (BIT) now permit only HSC (Higher Secondary Certificate) graduates from the science stream to enrol in a bachelor’s degree in engineering (Chowdhury & Sarkar, 2018).

The BITs became engineering universities in 1999 through a government ordinance. Nine engineering universities have offered engineering degree programs leading to bachelor, master, and PhD qualifications (Alam, Parvin, & Roslan, 2020). These universities offer a 4-year bachelor’s degree program (Chowdhury & Sarkar, 2018). Entry to these universities is restricted to HSC graduates only. On the other hand, DE produced from polytechnic institutions do not qualify for admission into bachelor programs in these ‘elite universities’ (Alam & Forhad, 2021b; Alam, Forhad, & Ismi, 2020).

In Bangladesh, 49 public and 389 private polytechnic institutes offer a 4-year diploma engineering program (BANBIES, 2020) and a student must complete eight biannual semesters to become a diploma engineer. The Bangladesh Institute of Technology-Dhaka became a university and rebadged Dhaka University of Engineering and Technology (DUET) in 2003. Like other engineering universities, DUET offers degree programs leading to bachelor’’s, master’s, and PhD degrees. However, the difference is that only diploma engineers are allowed to attend DUET. Table 1 compares the course distribution amongst DE (Diploma Engineering at polytechnics), DUET, and BUET programs in civil engineering. DUET graduates had already spent 4 years in polytechnics doing engineering, indicating it takes 8 years officially to become a fully fledged engineer. In contrast, graduates from other engineering universities—BUET—spent only 4 years completing the same engineering programs.

Conceptual framework

Given the research focus, three topics (role of education on development; effect of SES on education; and influence of education and SES on professional achievement) are covered.

Role of education: engineering education

The core purpose of primary education is to instil citizenship and socialisation skills, while secondary education is about delivering adequate skills and knowledge to equip young people with the means to face challenges and advance their social and learning development (Banerjee et al., 2019; Ware, 2019). Secondary education also produces a semi-skilled labour force and supplies graduates who could go on to tertiary education (Jones, 2008). Finally, tertiary education mainly provides a skilled workforce in various highly diverse fields of endeavour with professional qualifications (Murphy & Poist, 2007).

Tertiary education mainly comprises university and polytechnic delivery modes (Lewis 1991), and it functions to produce a highly skilled labour force for specific vocations (Wu, 2017). For example, a university’’s primary purpose is to produce elite leaders/administrators who have expertise in their field of endeavour to run the country, and polytechnics supply skilled-based professionals mainly to boost economic activity and diverse industries (Newman, 1852; Triyono & Mateeke Moses, 2019; Young & Hordern, 2020). Highly educated people are more likely to adapt to rapidly changing knowledge-based technologies and are more likely to earn more. In such ways, education could help offset the effects of SES in achieving a balanced society.

Engineering education wields a significant impact on individuals’ success in the labour market (Egerton, 2002; Riddell & Song, 2011). It also allows individuals to flourish in their lives, regardless of their birthplace, social background, race, ethnicity, or gender (Alam & Forhad, 2021b). Engineering education produces technically skilled human resources, which is the fundamental key to economic progress. Trace (2015) highlighted a direct link between the enrolment rate in engineering education and economic growth. Most economic systems and public infrastructure to this day greatly rely on what engineers can design and build. While engineering education plays a significant role in national economic advancement, it also significantly improves individuals’ living standards (Lucena & Schneider, 2008; Trace, 2015). Therefore, a substantial engineering education should preferably offset the effect of SES to play its desired role.

SES and education

Several scholars (Jencks et al., 1972; Marjoribanks, 1979; Noel & de Broucker, 2001; Poon, 2020) consistently demonstrated a positive relationship between SES and education achievements. In the late 1990s, Bos et al. (1999) and McDermott and Spencer (1997) argued that students from lower-income families are more likely to encounter academic challenges in schools. Although it is not unanimously clear, many studies explain that such effects range from the inequitable distribution of resources and opportunities to serious problems in families’ day-to-day interactions with others in society (Conger et al., 2002; Mistry et al., 2002).

Perry (2012) and Alam and Forhad (2021a) argued that schools with more students from a higher SES often secure higher scores compared to the national average. Students with lower SES studying at such schools also perform well, which may suggest a group of high-SES students typically create a differentiated school environment where good scores can be attained. As well as school support, parents’ education status, and income positively correlate to academic expectations for their children, especially if these variables are already advantageous (Child Trends, 2015; Davis-Kean, 2005; Neuenschwander et al., 2007; Triventi, 2013; Tynkkynen et al., 2012).

Perry (2012) argued that the opposite is true for students with lower SES. When these students are grouped in a school, this simply exacerbates the poorer education they receive. For example, Davis-Kean (2005) and Neuenschwander et al. (2007) argued that lower SES parents usually have lower expectations than their high-SES counterparts and are less likely to invest in their children’s education. Although the relationship between SES and student outcomes is well established in the literature, few analyses have examined the effect of SES in university engineering. Since a prior engineering program likely offers an absolute advantage to undergraduate students, they are more likely to overcome the effects of SES in their subsequent program in the same discipline.

Education: professional achievement

Mincer (1958), Schultz (1961), Becker (1964), and Stiglitz (1975) argued that individuals become human capital after receiving education and training. They believed that education is a highly instrumental and necessary component to enhance an individual’s productivity. However, Spence (1973) argued that even if education does not always contribute substantially to an employee’’s productivity, it still offers the ‘value to both the employer and employee’. He also claimed that if an apt ‘cost/benefit structure’ prevails, ‘good employees’ would seek ‘more education’ in order to signal that their worth and skills have improved. Hence, Spence (1973) further noted that education credentials ‘signal’ employers about the competitive parameters that the potential employees will have to address in the labour market.

Neoclassical economists also believe that individuals choose education and training to maximise their earnings. Therefore, education and training can be considered an investment (Tan, 2014). Blaug (1992) further claimed that individuals consider their present enjoyment and pecuniary and non-pecuniary benefits while choosing education as an investment decision. Given the growing popularity of the concept higher education as a private good, students having a higher SES might be able to take advantage of such investment. Although the widespread desire for social betterment can be achieved through a universal education system, higher education opportunities are not universal, regardless of what high-, middle-, and low-income countries aspire to. Using data on 55 countries with 50% or above higher educated individuals, Marginson (2016) shows that education’s expansion is not making progress because elite institutions do not provide equal social access.

Pickety (2014) and Piketty and Seaz (2013) argued that elitism in higher education has dramatically aggravated income inequality amongst highly educated graduates. Family income and social capital strongly influence access to both elite higher education and professional opportunities (Rivera, 2015; Soares, 2007). Marginson (2019) argued that the relationship between education and work is heterogeneous, and it is impossible to formulate a theory to explain such complex dynamics. In such an environment, SES’s effect is not only limited to education but also extended to professional achievement. This paper, the first of its kind, argues that despite a longer education in similar academic programs, socioeconomic factors remain a critical component for engineers’ academic and professional achievements.

Research methodology

Given the nature of the research questions, we used an individualistic approach to selecting tools (Bell, 2010). This research is largely based on both qualitative and quantitative analysis methods. To examine the effect of SES on further academic and career advancement, we first employ a qualitative analysis of secondary data to describe the differences in SES between BUET and DUET graduates. We then adopt an empirical model to explain whether SES has a causal impact on academic achievement in HSC and DE levels. This model uses primary source data. While the interpretations of findings of first and second research issues are mainly used to chalk out the third research question, semi-structured interviews were also conducted with the employersFootnote 3 and academicsFootnote 4 to generate some deeper insights. This will support a way forward that can offset the impact of SES in achieving academic and professional successes. The following sub-section explains ‘descriptive analysis’ before explaining the ‘empirical model’.

Descriptive analysis and data

‘Descriptive analysis’ mainly examines the impact of SES on further academic and career advancement by comparing BUET and DUET graduates. In doing so, three parameters were compared: socioeconomic background, academic performance,Footnote 5 and career advancement. Students from urban and rural areas, parents’ education and income, and gender were examined to understand the socioeconomic background. The parameters for academic performance include secondary school certificate (SSC), diploma engineering certificate, first-degree engineering certificate, and SSC, HSC, and first-degree engineering certificate, respectively, for DUET and BUET graduates.

The parameters for career advancement include ‘employability’ and engagement in higher education graduates received within the first 3 years of completing the first degree. Mid- and top-management positions occupied by graduates were not considered because these positions in a developing country are primarily connected with the length of service. It is therefore someone who is employed earlier would normally hold a mid- and senior management position earlier compared to the counterpart employed later. Furthermore, to be engaged in a public sector job, there is an age restriction. Moreover, the first cohort of DUET students graduated in 2008. Contact addresses of the graduates who passed the targeted programs at BUET and DUET since 2008 were collected and these people were invited to participate in the online survey. A structured questionnaire was provided to understand the further progress that graduates from both institutes made in their career.

Responding to the advice of the University Grants Commission, BUET started archiving the data electronically in the early 2000s, while electronic data of DUET dated back to 2005. ‘Descriptive analysis’ used the electronically preserved data of these institutions from 2005 to 2018. Neither one has a ‘data archive’ that is publicly available. Researchers may collect the raw data via a personal communication. Therefore, the researchers compiled and analysed the data. Almost all the programs offered by BUET and DUET are similar although both do have distinct programs. We only compiled the data of all students enrolled in similar programs in both institutions for ‘descriptive analysis’.

Empirical model and primary data

To understand the impact of SES on academic achievement in HSC and DE levels, the following empirical model is adopted in addition to ‘descriptive analysis’:

where yi is the CGPA in HSC or DE exam; SES is a vector of socioeconomic indicators: urban, parental education, and parental income; x is the vector of other control variables—GPA in SSC, gender, high school location, and college location. The coefficient of interest is α1, which is expected to be positive and statistically significant. This estimate suggests that the SES increases GPA in higher secondary or equivalent provision.

We now consider the GPAs in bachelor levels and extend the empirical model in Eq. 1 by incorporating another variable for 4-year engineering education. This model makes it possible to discover whether 4-year additional engineering education impacts on subsequent academic achievements:

where DE is a binary indicator for students who graduated from the diploma program. It is expected that an additional engineering education in the DE program wields a significant impact on GPA at the undergraduate level. To answer whether the 4-year DE program mitigates the effect of SES in academic achievement, we use the following model with an interaction model:

To determine the sample size for primary data, we mostly consulted the administrative data of BUET and DUET from 2005 to 2018 and considered the four largest common disciplines: civil engineering (CE), computer science and engineering (CSE), electrical and electronics engineering (EEE), and mechanical engineering (ME). We conducted a primary survey from the graduates in these programs for causal analysis. Approximately 120 students graduated from each department, indicating that the population size is 6720.

To calculate a representative sample size, we use the following Yamane (1967) formula:

where n is the sample size, N is the total number of graduates, and e is the significance level or the level of precision. As we collected graduate information for 2005 onward, it is highly likely to have a lower response rate. Therefore, we assumed that the precision level is 10%, indicating that the sample size is 98 for each institution. Using information provided by the departments of the respective universities, we contacted the section representative in each academic session and requested them to collect at least seven online responses from their batchmates.

Findings and discussions

This section first offers a descriptive analysis of socioeconomic backgrounds, academic achievements, and professional success of BUET and DUET graduates. We then discuss whether SES has a causal impact on educational achievements in higher secondary and DE levels. We also explain whether the 4-year DE program mitigates SES on academic achievements in engineering education and professional advancement. Finally, we describe a way forward that can help offset the impact of SES in achieving academic and professional successes.

Descriptive analysis: socioeconomic backgrounds

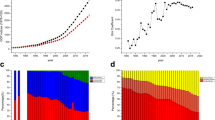

We considered three main socioeconomic indicators: location, parental education and income, and gender. Basing the schools’ location where graduates attended for SSC, location indicator is categorised into urban and rural. Figure 1 shows that a relatively higher portion of DUET students were from rural areas while a larger ratio of BUET students had urban origins. For example, on average, 79% and 17% of DUET and BUET graduates, respectively, are from rural areas, while DUET and BUET, again respectively, share 21% and 83% urban portion in the last 14 years.

To compare parental education backgrounds, we considered two categories of education, namely secondary and upper education. Secondary provision was considered a benchmark since Bangladesh is one of the best-performing countries in achieving the Millennium Development Goals. Consequently, most parents should ideally have at least completed secondary education. A higher percentage of parents of DUET students only studied up to secondary education, while a significant portion of parents of BUET students are highly educated. The percentage ratios between secondary and upper education completed parents of BUET and DUET students are, respectively, 54:46 and 82:18 (Fig. 2). Similarly, Fig. 3 depicts the trends of parental incomeFootnote 6 of BUET and DUET students. Only 13% of DUET students came from an upper-class family, while 47% were from BUET.

Females from a privileged SES in developing countries would normally undertake higher education and subsequently get into the job market. Fig. 4 also shows a relatively higher percentage of female students enrolled in BUET. These statistics suggest that BUET students have a stronger SES than their DUET counterparts.

Descriptive analysis: academic backgrounds

Students of BUET and DUET have very similar secondary education backgrounds. For example, both groups appeared in the Junior School Certificate (JSC) and SSCFootnote 7. They then appeared either in HSC or diploma engineering programsFootnote 8. HSC graduates from the science stream can be admitted to any university, including BUET, and DE graduates can appear only for DUETFootnote 9. SSC graduates looking for an immediate job are usually admitted to the DE program.

Figure 5 shows the trends of cumulative grade point of average (CGPA) in the SSC exam. Students enrolled in BUET always have a better CGPA in SSC compared to their counterparts in DUET. However, the CGPA is increasing over time in both groups. One potential reason for this is the overall improvement in academic attainment throughout the country. Figure 6 illustrates the academic achievement trends in HSC and diploma engineering programs. They also have the same trends in the whole sample period which means the performance of HSC graduates is better than DE. After graduating from the DE program, getting a job in the public sector is highly competitive, whereas the private sector mostly absorbs them in sub-managerial positions. Upon realising that a ‘bachelor qualification’ is a ‘must’ in order to be promoted in an executive position, diploma engineers attempt to continue further education in DUET.

Descriptive analysis: further academic and professional achievements

Before exploring further academic and professional achievements of engineers who graduated from the BUET and DUET, let us note their first-degree engineering program academic performance. Although DUET students have a prior diploma in the engineering program, they achieve less in their first-degree program compared to their BUET counterparts (Fig. 7).

Figure 8 compares the professional achievement between these two groups. On average, 40% of DUET graduates start as executives while approximately 76% are from BUET. Figure 9 shows BUET and DUET graduates’’ further education trends in a postgraduate program or professional career. Since BUET and DUET are located in Dhaka, the MBA degree offered by Dhaka UniversityFootnote 10 should be the first preference for graduates of both institutions if they wish to continue further study. Consequently, we counted how many of our sample graduates were enrolled in Dhaka University for the MBA program. Panel B of Fig. 9 shows that approximately 19% of BUET graduates enrolled in the MBA program at Dhaka University. At the same time, it is only 3% for DUET graduates. However, a higher proportion of DUET graduates enrol in private universities for their MBAs while a negligible number of BUET graduates went to private universities. Panel A of Fig. 9 confirms that approximately 39% of BUET graduates go overseas either for higher studies or professional careers, while the number for DUET counterparts is negligible.

Estimated results from the empirical model

The above ‘descriptive analysis’ implies that BUET graduates are associated with a higher SES than their DUET counterparts. These statistics confirm that BUET graduates have a relatively higher academic achievement in most cases. Consequently, one may argue whether the SES affects academic achievement. Additionally, DUET graduates have a 4-year diploma engineering education prior to getting their first degree in engineering while BUET counterparts do not. Therefore, engineering education at the undergraduate level may offer DUET students an advantage in their subsequent engineering programs, although most of them come from lower socioeconomic backgrounds. Someone may argue whether an additional 4-year engineering education, in such case DE, affects academic and professional achievements in subsequent education and professional careers. On this basis, whether this DE program helps to overcome SES’’s effects in the first degree or the professional career opportunities is open to question.

Using Eq. 1, Table 2 shows SES’’s effect on higher secondary provision and polytechnics’’ academic achievement. Column 1 shows the estimated impact of parental education on academic achievement. The estimated 0.501 is positive and statistically significant. Similarly, columns 2 and 3 show significant estimates and imply that socioeconomic status leads to academic success. Table 2 shows that schools located in urban areas, previous academic achievements, and peer effects have significant and positive impacts on higher secondary and polytechnic educational attainments.

As DUET students already have a 4-year engineering education, it would be interesting to examine how a prior engineering program in a polytechnic affects subsequent engineering education when taking socioeconomic factors into account. Using Eq. 3, column 1 in Table 3 shows the estimated effect of the DE on academic achievement at the bachelor level. The estimated effect is 0.231 and it is not statistically significant, indicating that a prior engineering program does not significantly influence academic achievement in follow-up education in the same discipline. Column 1 also shows that the effect of parents’ level of education is 0.451 and statistically significant. This outcome suggests that students’ academic achievements are positively influenced by their parental education.

Columns 2 and 3 show the same positive effect, but there is no statistically significant effect concerning DE. Column 4 in Table 3 indicates the estimated impact of the interaction term between socioeconomic factor and DE. This term’’s estimated effect is not statistically significant, suggesting that polytechnic graduates with better educated parents do not influence subsequent education. In this case, the impact of DE is not statistically significant. Columns 5 and 6 document similar results in that polytechnic graduates with higher parental education or urban background are not more likely to achieve much academically. Despite having a 4-year additional engineering education, a polytechnic program does not significantly influence their subsequent program.

Since English is the language of instruction in both institutions, we find that English proficiency measured by average GPA in SSC and HSC or DE statistically affects academic achievement. Table 3 shows that gender does not wield a significant effect while school location and peers do have a positive impact. A positive and statistical peer effect implies that social capital and networking have a strong influence. As BUET has a long history, it has a stronger alumni association where networking is much more effective than for DUET.

The above-estimated results imply that graduates who have completed at least 8 years of engineering education lag behind their privileged socioeconomic counterparts with only 4-year engineering education. We also conducted semi-structured interviews with the major employers who recruit engineering graduates from both institutions. Most of them argued that BUET graduates are inherently more competent in oral communication. This language proficiency might be inherent from the privileged SES and a wider network. This is how DUET graduates probably fall behind BUET even DUET has an 8-year engineering education program. Both BUET and DUET graduates completed almost the same number of credit hours at the bachelor level, and government and other organisations accredit their programs at national and international levels.

These situations in turn generate questions concerning both ‘human capital’ and ‘signaling’ theories. Establishing the differenceFootnote 11 between ‘human capital’ and ‘signaling’ theories is a subject of striking controversy in the discourse of education economics (Connelly et al., 2010). While ‘human capital’ theory suggests that education increases wages/salaries by aggregating ‘productivity’, ‘signaling theory’ claims that education increases people’s wages simply because it is a signal of the ‘employees’ ability’Footnote 12 (Connelly et al., 2010). Education credentials represent a proxy of all attributes that a potential candidate may have in the labour market; this is a key tenet of ‘signaling theory’ (Weiss, 1995). For this reason, it is highly likely that graduates from both institutions (BUET and DUET) will have the opportunity to do well in the recruitment process.

An employer can choose the best potential candidate through the recruitment process. In contrast, some recruitment processes within the country have discouraged DUET graduates from qualifying for them. For example, the engineering division of the Bangladesh Army and some commercial banks (Dutch Bangla Bank Limited-DBBL) have imposed an embargo on DUET graduates when positions are advertised. While DUET authorities contacted these employers asking to explain the embargo, further explanation was not forthcoming. Although BUET and DUET graduates have a 4-year undergraduate degree, allowing only those from one institution to apply for jobs is discrimination. Moreover, the discriminated against DUET graduates have an additional 4-year diploma engineering qualification. It appears that while academic results are appreciated, studying for a longer period of time tends to be ignored in the labour market. In other words, signaling theory’s emphasis on overall attributes achieved through education credentials may only partially work. Therefore, findings may suggest that polytechnic education does not help the graduates obtain subsequent academic status and professional careers.

Education offered at lower education levels (such as primary and secondary school) enhances productivity/human capital (Perry, 2012; Triventi, 2013; Tynkkynen et al., 2012). Students accrue literacy, numeracy, critical thinking, problem-solving skills, and other basis ones while at school. School-life also plays an important role on the development of character and personality (Triventi, 2013). Having said that, an additional investment in students from privileged socioeconomic backgrounds supplements and complements what schooling sets out to achieve. Such investments may also ensure students from a privileged SES will obtain greater success than others (Tynkkynen et al., 2012). This trend continues into higher education and the job market which may force both the human capital and signaling theories to seek other explanations (Alam, 2021). Neither of these theories is faultless although it seems that signaling theory should work well in the context of tertiary education (Connelly et al., 2010).

While the human capital acquired initially via schooling often benefits individuals in securing a position in higher education, the time spent acquiring a degree itself does not necessarily contribute substantially to better human capital always. It may simply support the ‘signaling function’. Moreover, obtaining a degree in Bangladesh is not the only ‘signaling factor’ in the labour market because a ‘large part of signaling’ also depends on firstly, institution from where the degree is acquired; secondly, its location; and thirdly, the heritage of the institution (Alam, 2021). This research finds that SES background has become an influencing part of ‘signaling function’ for engineers.

As engineering is mainly an applied science—related program (Feibleman, 1961; David, 1998), Johansson (2000) argued that courses in engineering education mostly consist of both lectures and hands-on laboratory exercises. The underlying instruction mode is to teach theories first and then verify them through practical exercises. Engineering faculty members teach courses and offer innovation through their research activities (Downey, 2009). Riley (2017) emphasised a rigorous and evidence-based engineering research and education. Compared with other academic disciplines—business, humanities, and social sciences—engineering education is a more practice-driven education.

The availability of logistical support for a practice-driven program is crucial in shaping career progress. Because of the unavailability of such data, we mainly rely on official statistics on students’ enrolments and on semi-structured interviews on the subject of overcoming the socioeconomic effects. According to BANBEIS (Bangladesh Bureau of Educational Information and Statistics , 2020), the total enrolment in polytechnic institutions has more than doubled in the last 5 years. Unfortunately, teaching and laboratory-related logistics have not expanded. Using the same infrastructure and logistics, delivering diploma engineering education to these increased intakes is not ideal. In such cases, theory-driven lectures are overly emphasised to the detriment of practical instruction. The student and teacher ratio has also significantly increased. As a result, polytechnic institutions might not train their graduates as promised in their academic curricula.

Both HSC and diploma engineering students study some common subjects such as chemistry, English, physics, and mathematics which basically follow the same textbook content. The DE graduates studied additional core engineering courses in their respective disciplines that are not covered in the HSC. Despite these, DUET graduates cannot compete with the BUET counterparts. One probable reason could be that DE emphasises more in learning about subjects related to the specialised engineering discipline without focusing on common subjects, which are also vital aspects of the first-degree program.

It is also observed that in connection to the faculty recruitment for the common subjects—physics, English, mathematics, and chemistry—the HSC institutions usually recruit more qualified instructors compared to the polytechnics. For example, most instructors teaching DE programs are usually polytechnic graduates who teach these common subjects, while specialised teachers teach the same at the HSC level. Therefore, BUET students associated with higher socioeconomic backgrounds receive privileged education at HSC level compared to their DUET counterparts. The end result was that—despite graduating from a 4-year engineering program—DE students will likely achieve less academically and professionally. On the other hand, some may argue that the bachelor of engineering program is overly theory-driven with a heavy emphasis on ‘common subjects’. Since engineering is a practice-driven program, policymakers should ensure there is a meaningful link between school diplomas and postgraduate courses to achieve the desired outcomes in engineering education.

Conclusion

Comparing a 4-year engineering program with 8 years of completing graduates in the same discipline, we argue that socioeconomic status dominates prior engineering education to shape further academic and professional achievements. Findings also confirm that more years spent on engineering education fail to offset the influence of SES on academic and professional advancement. One of the potential reasons for such findings is the heterogeneous nature of education. Finally, our findings and discussions recommend improving the logistical infrastructure of education institutions, especially for students coming from a lower socioeconomic background.

Notes

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Scaling Procedures and Construct Validation of Context Questionnaire Data. Ch. 16 (OECD Publishing, 2017).

In this case, we mainly focus on the existing teaching and logistic infrastructure of the education institutions.

For employer perspectives on graduates’ employability skills (Bell, 2010), we mainly conducted semi-structured interviews with personnel from two multinational corporations and government institutions.

These were from both universities.

Both at pre-engineering programs and engineering program.

The income categories are defined by following the government’s segmentation as prescribed by BBS (Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics).

After completing the JSC exam, some students can enrol in a 2-year SSC-Vocational (SSC-VOC) program, which is equivalent to the SSC.

SSC graduates can go either into a HSC or DE program while SSC-VOC can enrol only in the DE program. Therefore, DE graduates from SSC-VOC have at least 6 years of vocational and engineering education.

DUET graduates originally from SSC-VOC have at least 10 years of technical and engineering education while BUET students have a 4-year engineering education.

MBA of Dhaka University (specifically offered by the Institute of Business Administration) is considered the most elite program in the country. Many engineers want to study this program to sharpen their managerial skills.

We believe that both theories are in some contexts very similar and it is not necessarily a case of ‘either-or’.

It could refer to various kinds of abilities such as innate attributes.

References

Alam, G. M. (2021). Clustering education policy in secondary provision: Impact on higher education and job market. International Journal of Educational Reforms, 30(1), 56–76.

Alam, G. M., & Forhad, M. A. R. (2021a). Clustering secondary education and the focus on science: Impacts on higher education and the job market in Bangladesh. Comparative Education Review, 65(2), 310–331.

Alam, G. M., & Forhad, M. A. R. (2021b). Roadblocks to university education for diploma engineers in Bangladesh. Higher Education, Skills and Work-Based Learning, 11(1), 59–77.

Alam, G. M., Forhad, M. A. R., & Ismi, A. (2020). Can education as an ‘International Commodity’ be the backbone or cane of a nation in the era of fourth industrial revolution? - A comparative study. Technological Forecasting and Social Change. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2020.120184.

Alam, G. M., Mishra, P. K., & Shahjamal, M. M. (2014). Quality assurance strategies for affiliated institutions of HE: A case study of the affiliates under National University of Bangladesh. Higher Education, 68(2), 285–301.

Alam, G. M., Parvin, M., & Roslan, S. (2020). Growth of private university business following “oligopoly” and “SME” approaches: An impact on the concept of university and on society. Society and Business Review. https://doi.org/10.1108/SBR-06-2020-0083.

BANBEIS Reports from (2020). Bangladesh Education Statistics. Ministry of Education

Banerjee, A., Ferrara, F. L., & Victor, O. (2019). Entertainment, education, and attitudes toward domestic violence. AEA Papers and Proceedings, 109(1), 133–137.

Becker, G. (1964). Human capital: A theoretical and empirical analysis with special reference to education. University of Chicago Press.

Bell, J. (2010). Doing your research project. Open University.

Blaug, M. (1992). The methodology of economics: Or, how economists explain. Cambridge University Press.

Bos, J. M., Huston, A. C., Granger, R. C., Duncan, G. J., Brock, T. W., & McLoyd, V. C. (1999). New hope for people with low incomes: Two-year results of a program to reduce poverty and reform welfare.

Child Trends (2015). Parental expectations for their children’s academic attainment. Available at. http://www.childtrends.org/wpcontent/uploads/2012/07/115_Parental_Expectations.pdf. Accessed 20 August 2020.

Chowdhury, R., & Sarkar, M. (2018). Education in Bangladesh: Changing contexts and emerging realities. In R. Chowdhury, M. Sarkar, F. Mojumder, & M. Roshid (Eds.), Engaging in educational research. Education in the Asia-Pacific region: Issues, concerns and prospects, vol 44. Springer.

Conger, R. D., & Donnellan, M. B. (2007). An interactionist perspective on the socioeconomic context of human development. Annual Review of Psychology, 58(1), 175–199.

Conger, R. D., Wallace, L. E., Sun, Y., Simons, R. L., McLoyd, V. C., & Brody, G. H. (2002). Economic pressure in African American families: A replication and extension of the family stress model. Developmental Psychology, 38(2), 179.

Connelly, B. L., Certo, S. T., Ireland, R. D., & Reutzel, C. R. (2010). Signaling theory: A review and assessment. Journal of Management, 37(1), 39–67.

David, P. A. (1998). Common agency contracting and the emergence of "Open Science" Institutions. The American Economic Review 88(2), 15–21

Davis-Kean, P. E. (2005). The influence of parent education and family income on child achievement: The indirect role of parental expectations and the home environment. Journal of Family Psychology, 19(2), 294–308.

Downey, G. L. (2009). What is engineering studies for? Dominant practices and scalable scholarship. Engineering Studies 1(1), 55–76.

Egerton, M. (2002). Higher education and civic engagement. The British Journal of Sociology, 53(4), 603–620.

Feibleman, J. K. (1961). Pure Science, Applied Science, Technology, Engineering: An Attempt at Definitions, Technology and Culture 2(4), 305-317.

Goodman, D., (2014). Class in contemporary China: Polity Press.

Green, L. W. (1970). Manual for scoring socioeconomic status for research on health behaviour. Public Health Reports, 85(9), 815–827.

Jencks, C., Smith, M., Acland, H., Bane, M. J., Cohen, D., Gintis, H., Heynse, B., and Michelson, S., (1972). Inequality: A reassessment of the effect of family and schooling in America: Basic Books.

Johansson, C. (2000) Communicating, Measuring and Preserving Knowledge in Software Development, Kaserntryckeriet AB, Sweden.

Jones, M. K. (2008). Disability and the labour market: A review of the empirical evidence. Journal of Economic Studies, 35(5), 405–424.

Kincaid, A. P., & Sullivan, A. L. (2017). Parsing the relations of race and socioeconomic status in special education disproportionality. Remedial and Special Education, 38(3), 159–170.

Lewis, M. S. (1991). The polytechnics: a peculiarly British phenomenon. Regional Development 2(4), 24–34.

Liu, J., Peng, P., & Luo, L. (2020). The relation between family socioeconomic status and academic achievement in China: A meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 32, 49–76.

Lucena, J., & Schneider, J. (2008). Engineers, development, and engineering education: From national to sustainable community development. European Journal of Engineering Education, 33(33), 247–257.

Marginson, S. (2016). The worldwide trend to high participation higher education: Dynamics of social stratification in inclusive systems. Higher Education, 72(4), 413–434.

Marginson, S. (2019). Limitation of human capital theory. Studies in Higher Education, 44(2), 287–301.

Marjoribanks, K. (1979). Families and their learning environments: An empirical analysis: Routledge

McDermott, P. A., & Spencer, M. B. (1997). Racial and social class prevalence of psychopathology among school-age youth in the United States. Youth & Society, 28(4), 387–414.

Mincer, J. (1958). Investment in human capital and personal income distribution. Journal of Political Economy, 66(4), 281–302.

Mistry, R. S., Vanderwater, E. A., Houston, A. C., & McLoyd, V. C. (2002). Economic well-being and children’s social adjustment: The role of family process in an ethnically diverse low-income sample. Child Development, 73(3), 935–951.

Murphy, P., & Poist, R. F. (2007). Skill requirements of senior-level logisticians: A longitudinal assessment. Supply Chain Management, 12(6), 423–431.

Neuenschwander, M. P., Vida, M., Garrett, J. L., & Eccles, J. S. (2007). Parents” expectations and students” achievement in two western nations. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 31(6), 594–602.

Newman, J. H. (1852). The idea of university defined and illustrated. Oxford University Press.

Noel, S., & de Broucker, P. (2001). Intergenerational inequities: A comparative analysis of the influence of parents’ educational background on length of schooling and literacy skills. In W. Hutmacher, D. Cochrane, & N. Bottani (Eds.), In pursuit of equity in education: Using international indicators to compare equity policies (pp. 277–298). Kluwer Academic.

Perry, L. B. (2012). Causes and effects of school socio-economic composition? A review of the literature. Education and Society, 30(1), 19–35.

Pickety, T. (2014). Capital in the Twenty-First Century, Belknap Press, Cambridge.

Piketty and Seaz (2013) in the text and reference is Piketty, T. and Seaz, E. (2013) A Theory of Optimal Inheritance Taxation Econometrica, 81(5), 1851–1886.

Poon, K. (2020). The impact of socioeconomic status on parental factors in promoting academic achievement in Chinese children. International Journal of Educational Development, 75, 102175.

Riddell, W. C., & Song, X. (2011). The impact of education on unemployment incidence and re-employment success: Evidence from the US labour market. Labour Economics, 18(4), 453–463.

Riley, D. (2017) Rigor/Us: Building Boundaries and Disciplining Diversity with Standards of Merit. Engineering Studies 9 (3), 249–265.

Rivera, L., (2015). Pedigree: How elite students get elite jobs: Princeton

Schultz, T. (1961). Capital formation by education. Journal of Political Economy, 68(6), 45–67.

Soares, J. (2007). The power of privilege: Yale and America’s elite colleges. Stanford University Press.

Spence, M. (1973). Job marketing signalling. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 87(3), 355–374.

Stiglitz, J. E. (1975). The theory of “screening”, education, and the distribution of income. American Economic Review, 65, 283–300.

Tan, E. (2014). Human capital theory: A holistic criticism. Review of Educational Research, 84(3), 411–445.

Trace, S. R. (2015). The role of the engineer in developing countries. Proceedings of the Institute of Civil Engineers- Municipal Engineers, 103(2), 105–118.

Triventi, M. (2013). Stratification in higher education and its relationship with social inequality: A comparative study of 11 European countries. European Sociological Review, 29(3), 489–502.

Triyono, M. B., & Mateeke Moses, K. (2019). Technical and vocational education and training and training in Indonesia. In B. B. Paryono (Ed.), Vocational education and training in ASEAN member states. Perspectives on Rethinking and Reforming Education. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-6617-8_3.

Tynkkynen, L., Tolvanen, A., & Salmela-Aro, K. (2012). Trajectories of educational expectations from adolescence to young adulthood in Finland. Developmental Psychology, 48(6), 1674.

Ware, J. K. (2019). Property value as a proxy of socioeconomic status in education. Education and Urban Society, 51(1), 99–119.

Weiss, A. (1995). Human capital vs. signalling explanations of wages. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 9(4), 133–154.

Wu, X. (2017). Higher education, elite formation and social stratification in contemporary China: Preliminary findings from the Beijing College Students Panel Survey. Chines Journal of Sociology, 3, 3–31.

Yamane, T. (1967). Statistics, An Introductory Analysis, New York: Harper and Row.

Young, M., & Hordern, J. (2020). Does the vocational curriculum have a future? Journal of Vocational Education & Training, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/13636820.2020.1833078.

Zhao, W. (2012). Economic inequality, status perceptions, and subjective well-being in China’s transitional economy. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 30(4), 433–450.

Acknowledgements

We greatly acknowledge the comments made by the reviewers and Professor Simon Marginson (Editor-Higher Education). Without their thorough input, the manuscript would not have reached its enriched version. We would also like to express our gratitude to Professor Christine Ennew Provost, University of Warwick and Professor Charlie Russo, University of Dayton for their kind insights with innovative ways to deal with the reviewers’ comments. Especial thanks to Mr. Md. Moniruzzaman, Deputy Registrar, DUET who died from being infected by COVID-19 and Ms. Morsheda Parvin who provided a unique support for data collection.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Alam, G.M., Forhad, M.A.R. What makes a difference for further advancement of engineers: socioeconomic background or education programs?. High Educ 83, 1259–1278 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-021-00741-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-021-00741-4