Facebook is shutting down its ill-fated trending news section after four years, according to a company executive.

The company says the tool is outdated and unpopular. It also proved problematic in ways that hinted at Facebook’s later problems with fake news, political balance and the limitations of AI in managing the human world.

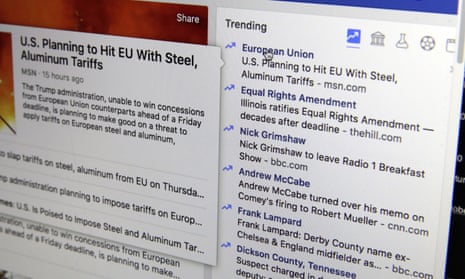

When Facebook launched “trending” in 2014 as a list of headlines appearing at the side of the main news feed, it aimed to steal users from Twitter by offering them a quick look at the most popular news stories.

It aligned with the pledge just a year earlier by Facebook chief executive, Mark Zuckerberg, to make Facebook a “personal newspaper” for users. But at that time fake news was not a popular term and no foreign country had been accused of trying to influence the US elections through social media, as Russia would be.

Trending news that year included the death of Robin Williams, Ebola and the World Cup.

Facebook is testing new features, including a breaking news label that publishers can add to stories to distinguish them. Facebook also wants to make local news more prominent.

Facebook’s head of news products, Alex Hardiman, said the company is still committed to real-time news. But instead of letting Facebook’s moderators make editorial decisions, there has been a subtle shift to let news organisations do so.

According to the Pew Research Centre, 44% of US adults get some or all of their news through Facebook.

Problems with the trending section emerged in 2016, when the company was accused of bias against conservatives, based on comments by an anonymous former contractor.

The contractor claimed Facebook downplayed conservative issues and promoted liberal causes.

Zuckerberg met prominent rightwing leaders at the company’s headquarters in an attempt at damage control. Yet two years later, Facebook still has not been able to shake the notion of bias.

In late 2016, Facebook fired the human editors who worked on trending topics and replaced them with software that was supposed to be free of political bias.

Instead, the software algorithm began to pick out posts that were getting the most attention, even if the information was bogus.

In early 2017, Facebook made another attempt to fix the trending section by including only topics covered by several news publishers. The idea was that coverage by just one outlet could be a sign that the news is fake.

The problems underscore the difficulty of relying on computers, or even AI, to make sense of the messy human world without committing obvious, sometimes embarrassing and occasionally disastrous errors.

Facebook appears to have concluded that trying to fix the headaches caused by the trending section was not worth the meagre benefits the company, users and news publishers saw in it.

“There are other ways for us to better invest our resources,” Hardiman said.

The breaking news label that Facebook is testing with 80 news publishers will let outlets such as the Washington Post add a red label to indicate that a story is breaking news.

“Breaking news has to look different than a recipe,” Hardiman said.

Another feature, called Today In shows people breaking news in their area from local publishers, officials and organisations. It’s being tested in 30 markets in the US.

Hardiman said the goal is to help “elevate great local journalism”.

The company is also funding news videos, created exclusively for Facebook by publishers it would not yet name. It plans to launch this feature in the next few months.

Facebook says the trending section was never popular. It was available only in five countries and accounted for less than 1.5% of clicks to the websites of news publishers.

While Facebook got attention for the problems the trending section had – perhaps because it seemed popular with journalists – neither its existence nor its removal makes much difference in regards to Facebook’s broader problems with news.

Hardiman said that ending the trending feature feels like letting a child go but Facebook’s focus is prioritising trustworthy, informative news that people find useful.