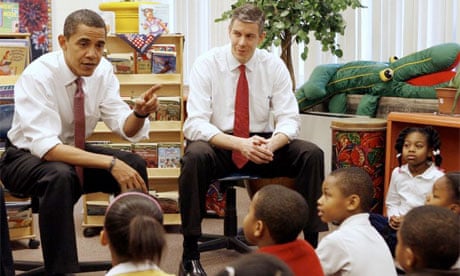

State schools in the US are failing not only its children, but also its national security, according to Thomas L Friedman's recent commentary in the New York Times on Secretary of Education Arne Duncan's 4 November speech. Friedman also praises Duncan's call to reform US education by infusing its teaching core from the top students in the US – a process modelled on the education systems in Finland and Denmark.

Significantly, Friedman discusses Duncan's criticism of education in the US without mentioning poverty a single time (just as Duncan mentioned teachers over four dozen times in his August speech in Little Rock, Arkansas, also without mentioning poverty. As evidence, Friedman cites the same "few data points" offered by Duncan.

Before examining the charges presented by both Friedman and Duncan, let's look at a state-to-state comparison in the US to illustrate the folly of making sweeping claims about educational quality with a "few data points". Two Southern states, Mississippi and South Carolina, share both a long history of high poverty rates (Mississippi at over 30% and SC at over 25%) and reputations for poor schools systems. Yet, when we compare the SAT scores (pdf) from Mississippi in 2010 (CR 566, M 548, W 552 for a 1,666 total) to SAT scores in SC (CR 484, 495, 468 for a 1,447 total), we may be compelled to charge that Mississippi has overcome a higher poverty rate than South Carolina to achieve, on average, a score 219 points higher.

This conclusion, based on a "few data points", is factually accurate, but ultimately misleading once we add just one more data point: the percentage of students taking the exam. Just 3% of Mississippi seniors took the exam, compared to 66% in South Carolina. A fact of statistics tells us that SC's larger percentage taking the exam is much closer to the normal distribution of the all seniors in that state, thus the average must be lower than a uniquely elite population, such as in Mississippi. Here, the statistics determined by the populations taking the exam trump the raw data of test averages, even when placed in the context of poverty.

Now, the claims made by Friedman based on the speech by Duncan: the data points praised by Friedman and used by Duncan – dropout rates, the relationship between education and economic success and the comparison of teacher pools among countries – appear, like the SAT scores, to be valid data points to draw conclusions about the quality of US schools. But the full picture proves that assumption to be flawed.

One of the most damning failures of the argument is that rigorous research by Gerald Bracey has shown us little positive correlation between measured educational attainment and the strength of any nation's economy. This is good political discourse, but the evidence isn't there.

The call to recruit the best and brightest students (as other top countries do, they always add) is also a compelling charge that falls apart when placed against evidence. Studies, again, have failed to show that such a simple process, in fact, achieves what we would expect.

Finally, the persistent refrain praising Finland and Denmark as "countries leading the pack in the tests that measure these skills" offers yet another simplistic conclusion that is compelling, but incomplete. Finland and Denmark, according to studies from Unicef in 2005 and 2007, have childhood poverty rates of 2.8% and 2.4% respectively, while the US childhood poverty rate is 21.9%. Further, Finland's entire population is 5 million people, while the US school system educates 50 million children, with 3.2 million teachers. In short, the full picture about populations reveals a "few data points" as more misleading than illuminating.

Does the US need better schools and do US children deserve the best teachers in every classroom possible? Of course. No one refutes either of these statements.

But these lofty goals cannot be attained as long as leaders refuse to acknowledge the historical pattern of social failures that are reflected in (and, too often, exacerbated by) US schools, such as high dropout rates for racial minorities and children living in poverty. Throughout the world, the full picture of any nation's schools reflects the social realities of that country; when schools appear to be failures, the facts show that social failures (the conditions of children's lives outside of school) are driving the educational data.

And we will certainly never address these social failures – and the truth about our schools – if political leaders and media voices refuse even to say the word "poverty", while promoting simplistic manipulation of data.